Zone II Flexor Tendon Repair

David B. Shapiro

Nathan A. Monaco

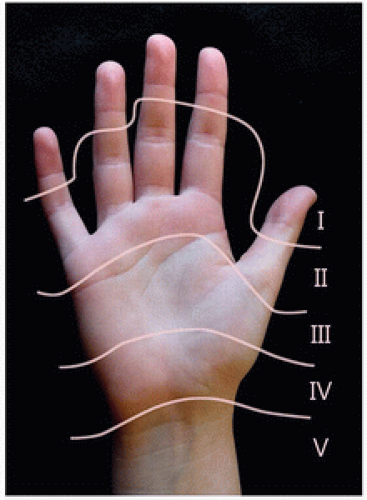

In flexor tendon parlance, the region between the distal palmar crease and the FDS insertion has been described in many ways, from Bunnell’s initial description as “no man’s land” (1) to McCash’s more descriptive “deathbed of many a stout profundus” (2,3) to Verdan’s present-day “zone II” (4) (Fig. 15-1). It is the area where the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) change position relative to one another within the confines of the fibroosseous digital sheath. Based on previous attempts at repair, Bunnell stated that tendons lacerated at this level “cannot [be joined] by suture with success… It is better to remove the tendons from the finger and graft in a new tendon” (1). Although some advocated primary repair as early as 1940 (including Bunnell, in certain circumstances), a long tradition of excision and grafting limited enthusiasm for tendon repair (6). Verdan’s promising early results (7) began to usher in a new era in tendon repair. Kleinert et al. (8) presented their 10-year experience in zone II tendon repairs, rehabilitated with an early, protected motion program, set the stage for the progressive advances in tendon repair that followed. Advancements in our knowledge of tendon biology and suture characteristics, the routine use of loupe magnification, more refined operative repair techniques, and better postoperative rehabilitation protocols have led to the establishment of primary tendon repair as the current standard of care for zone II flexor tendon lacerations (9).

At present, the goals of flexor tendon repair include precise approximation of the tendon ends to promote intrinsic tendon healing, creation of a repair site with sufficient strength to limit gap development during the entire recovery process, and development and execution of a rehabilitation protocol to limit tendon adhesion and maximize digital motion without causing rupture of the repaired tendon. Obtaining consistent, excellent results in these injuries remains challenging for surgeons, patients, and therapists alike.

ANATOMY

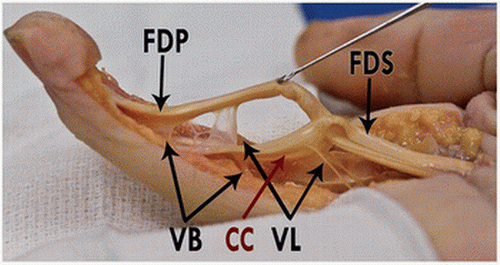

Digital flexion is provided by two tendinous extensions of the extrinsic forearm muscles, the FDS and FDP. The flexor pollicis longus tendon provides extrinsic thumb flexion. The FDP has one common muscle belly (often with a separate radial bundle directed toward the index finger) originating on the anterior-medial ulna and interosseous membrane, which sends individual tendons to insert on the distal phalanx of each finger. Lumbrical muscles originate from the four FDP tendons in the palm, with their own tendons joining the interosseous tendon and forming the radial lateral band. The FDS originates from multiple points on the distal humerus, ulna, and radius. In the midforearm, it divides into four distinct muscle bellies, with a superficial layer to the long and ring fingers, and a deeper layer to the index and small fingers. The FDS tendons lie superficial to the FDP in the palm, dividing, rotating, and inserting over the proximal third of the middle phalanx, with interconnections between the two FDS slips at Camper’s chiasm, over the PIP joint (10) (Fig. 15-2). While independent FDS function to the small finger is often absent, the tendon itself is almost always present (12).

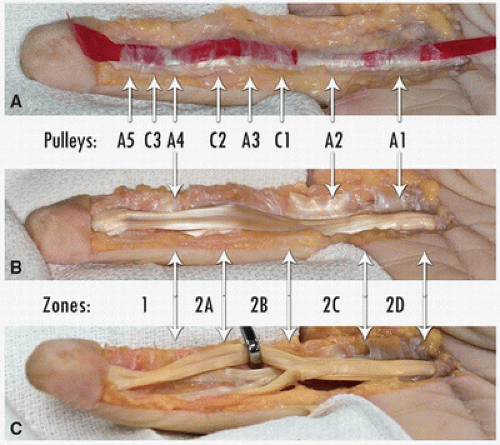

The fibrous retinacular sheath, or pulley system, consists of five annular and three cruciate condensations (also shown in Fig. 15-2). The sheath begins at the metacarpal neck and ends at the distal phalanx, although tenosynovial extensions to the wrist occur in the thumb and small finger (the radial and ulnar bursae). The sheath and synovial system function to maintain a

smooth gliding system for the tendons, to provide nutrition and lubrication, and, at the level of the pulleys, to keep the tendons close to the axis of joint rotation, increasing mechanical efficiency and preventing bowstringing. Intrinsic blood supply to the flexor tendons occurs through the vincula (Fig. 15-3), with relatively avascular areas beneath the A2 and A4 pulleys.

smooth gliding system for the tendons, to provide nutrition and lubrication, and, at the level of the pulleys, to keep the tendons close to the axis of joint rotation, increasing mechanical efficiency and preventing bowstringing. Intrinsic blood supply to the flexor tendons occurs through the vincula (Fig. 15-3), with relatively avascular areas beneath the A2 and A4 pulleys.

FIGURE 15-2 Flexor tendon pulley system. The annular pulleys are designated A1 through A5, with cruciate pulleys C1, C2, and C3. This specimen has a relatively thin A4. Tang’s subdivision of Zone II includes 2A which covers the long insertion of the FDS; 2B extending from the proximal edge of 2A to the distal edge of the A2 pulley; 2C covering the length of the A2 pulley; and 2D which is proximal to A2. (Tang JB. Flexor tendon repair in zone 2C. J Hand Surg Br 19(1): 72-75, 1994.) The actual repair can traverse more than one subdivision as the digit moves. Note how the FDS tightly encircles the FDP (held in the retractor) beneath and distal to the A2 pulley. |

Kleinert and Verdan described five flexor tendon zones on the palmar aspect of the hand, based on anatomic differences and healing potential (Fig. 15-1) (4,5). Zone II spans from the proximal aspect of the A1 pulley to the insertion of the FDS on the middle phalanx and can be further divided into subzone A through D (11) (Fig. 15-2).

INDICATIONS

With rare exception, complete zone II flexor tendon lacerations require surgical intervention. It is important to ascertain when the injury occurred, the mechanism, and (if possible) the position of the hand at the time of injury. Saw injuries, or those with a crushing component, for example, can cause tearing of tendon edges, leading to different challenges in repair and rehabilitation when compared to the clean tendon transections seen after sharp knife lacerations (13). Injuries that occur when the hand is closed will result in tendon lacerations well distal to the skin laceration.

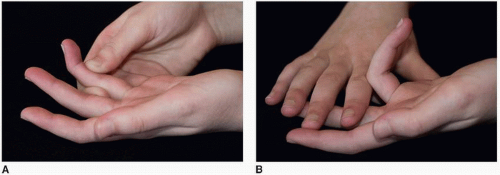

When examining the patient, make note of the location and degree of wound contamination to aid in planning incision extensions and to determine whether delaying repair will risk deep infection. Neurovascular examination should be performed to assess the integrity of the digital nerves. If both nerves are believed to be transected, more urgent exploration may be warranted if arterial repair is anticipated. The tendon laceration will often lead to an alteration of the normal resting digital cascade (Fig. 15-6A). Deep flexor tendon function is assessed by testing active flexion of the DIP joints. FDS function is tested by examining independent PIP flexion while the other digits are held extended (Fig. 15-4). X-rays are warranted to rule out any fractures or foreign bodies.

Emergent primary repair of complete zone II flexor tendon injuries is necessary only in cases with gross contamination or vascular injury requiring repair. Isolated tendon repairs are technically easier to do sooner rather than later, but a 1-week (or even 2-week) delay seldom changes the difficulty or outcome. While surgical repair should be performed expediently, it is appropriate to delay until there is a full, well-rested surgical staff, appropriate assistance, and time to do a meticulous repair of all the injured structures. As time passes, edema of the tendon ends, muscle shortening, and scar in the sheath make tendon approximation and passage of the tendon under the pulleys more difficult.

The most important step in preoperative preparation is a frank discussion with the patient regarding the implications of the injury, the anticipated outcomes, the importance of compliance in the therapy programs, and the required activity restriction. The patient should understand that unrestricted activity will need to be avoided for 3 months following surgical repair, that few patients will regain perfect motion, and that a few will require reoperation for rupture of the repair or stiffness.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Active infection and gross wound contamination: These may require debridement and a short delay in primary tendon repair.

Delayed presentation: Presentation after a couple weeks will likely make primary repair more difficult. Exploration is still warranted, with primary repair of at least the FDP if possible (partial or total FDS excision may be required to pass the FDP through the pulleys). The surgeon must be prepared for an alternative procedure if primary repair without undue tension cannot be performed—either tendon grafting or placement of a silicone tendon rod as the beginning of a two-stage tendon reconstruction.

Delayed presentation of an FDP laceration with intact FDS and good active PIP motion: Repair in this case risks damaging a functioning FDS in a case where, after exploration, primary repair may still not be possible. Tendon grafting or silicone rod placement should generally not be performed. A tenodesis of the FDP stump into the middle phalanx or A4 pulley can be performed in patients with passive DIP hyperextension.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

In this series, clinical and cadaver lab images are used to illustrate the points in the text.

The patient is brought to the operating room after the administration of a prophylactic antibiotic. Regional anesthesia combined with intravenous sedation or general anesthesia is preferred, as involuntary, uncontrolled flexion of the fingers at the completion of the procedure will be prevented by the block. The arm is prepped and draped in a standard fashion, with the sterile field extending above the elbow. With the patient in the supine position and the surgeon seated in the axilla, the arm is exsanguinated and an upper arm tourniquet inflated to 100 mm Hg of mercury above systolic pressure (less for small arms).

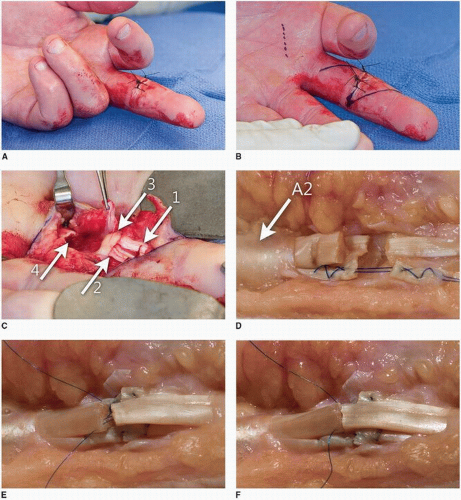

The initial laceration can be explored but will almost always require extension proximally and distally, with incisions either obliquely or along the midlateral line (Figs. 15-5 and 15-6B).

Midlateral incisions leave less scar over the tendons, but zigzag incisions may provide better exposure. Skin flaps are raised, identifying and protecting both neurovascular bundles. If nerve repair is required, the nerve and vessel are dissected free to allow for neurorrhaphy after the tendon repair.

The laceration in the tendon sheath is identified. The sheath can be opened along either side, proximal to A2 (A1 can be divided if necessary), between A2 and A4 (dividing A3 and the cruciate pulleys), or distal to A4, depending on the location of the injury. The tendon ends are seldom seen near the sheath opening. If the finger was flexed at the time of the injury, the distal ends will be well distal to the zone of injury when the digit is extended (Fig. 15-6C). The proximal ends may retract several centimeters, although FDP retraction is partially limited by the lumbrical attachments.

Tendon retrieval distally can be done by flexing the digit. If less than a centimeter of the FDP tendons is exposed, either open (“vent”) or remove the proximal half of A4. While it may be possible to withdraw the tendon distal to A4, place a suture, and pass the tendon back beneath the pulley, this limits the suture technique options and makes the epitendinous suture more difficult. Venting or even complete release of A4 is preferred to a weak repair or one that will not pass under the pulley (14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree