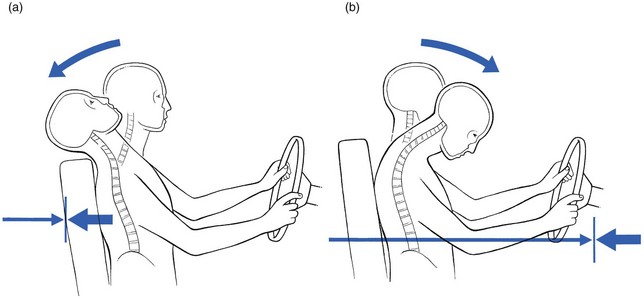

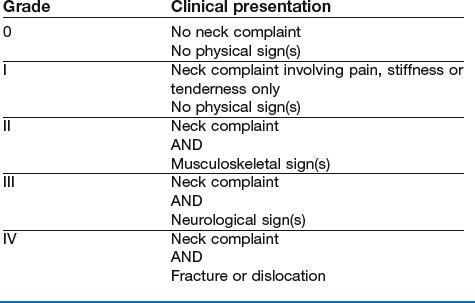

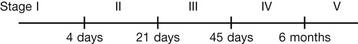

10 When a vehicle is struck from the rear, the occupants rarely have any warning and do not brace the muscles to prevent head movement. As a result, the body is propelled forwards and the neck hyperextends backwards well beyond the normal range of allowable movement (Fig. 10.1). This violent motion is followed by a less rapid forwards recoil into flexion that can often result in a head injury if the head impinges on the windscreen. Medical literature, in an attempt to find a proper definition, has so far described ‘whiplash injury’ in terms of the mechanism of the accident, the type of lesion that is caused or the clinical appearance after the injury. In 19951 the Quebec Task Force (QTF) proposed the following definition: The incidence is not precisely known. A figure of 1 per 1000 people per year has been suggested.2 Other studies in Canada mention 5000 whiplash cases a year in the province of Quebec, accounting for 20% of all insurance claims after motor vehicle accidents.3,4 In the United States 11 300 000 car accidents were reported for the year 1991, of which 2 690 000 were rear-end collisions and caused 85% of all whiplash injuries.5 The QTF, persuaded that proper diagnosis is difficult to achieve, has proposed two classifications: one according to the severity of the symptoms and signs (grades) (Box 10.1) and one according to the time elapsed since the accident (stages) (Box 10.2). Depending on the movement of the head during the accident, several lesions may occur, ranking from severe to moderate to slight. Hyperextension is the most common mechanism, followed by hyperflexion and lateral flexion.6 Hyperextension and distraction of the neck may rupture the anterior longitudinal ligament as well as some discs. A ruptured disc can lead to backward displacement of the vertebra lying above it – the upper facets then slide downwards on the lower – with damage to the spinal cord as a result.7 Spinal cord injuries after motor vehicle accidents occur most often in young car users in the 15–24 year age group.8,9 Hyperflexion injury may lead to fractures of the vertebral body – most fractures of the atlas10 and of the axis11 are the result of motor vehicle accidents – and/or to disruption of posterior ligaments and occasionally facet joint luxation. Recent retrospective studies have shown that the occurrence of disc lesions after whiplash injury is quite high12,13 and one prospective study indicates the value of clinical diagnosis.14 Most disc lesions are endplate avulsions and ruptures of the anterior annulus fibrosus. As the result of the hyperextension element during the trauma the disc may have fissured. The subsequent flexion or hyperflexion element causes displacement of disc material in a posterior direction. Davis et al describe a number of posterolateral disc lesions with radicular symptoms as the result of a hyperextension whiplash trauma.12 These herniations seemed to develop only after the acute phase and it took a few weeks for the radicular symptoms to appear. In postmortem studies Taylor et al describe the intervertebral disc as the most frequently damaged structure.15–17 Jónsson et al18 Also confirmed the large number of disc lesions after whiplash, and during surgery were able to confirm the findings from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Posterocentral protrusions lead to central, bilateral or unilateral pain in a multisegmental distribution: pain in the neck, trapezius and upper scapular area. On examination a symmetrical (mimicking a full articular pattern) or asymmetrical pattern of limitation is found. In acute cases the picture may be torticollis-like. For a detailed description of disc pathology, see page 145. Whiplash may also lead to problems at the level of the zygapophyseal joint capsules.19 Lord et al undertook a placebo-controlled prevalence study after whiplash and found that chronic cervical facet joint pain was common.20 Pain is felt unilaterally and is usually quite localized. A convergent or divergent motion pattern may occur, although any asymmetrical pattern is compatible. (Facet joint pathology is discussed on p. 163). Ligaments can become overstretched, leading to minor lesions,12 or may become adherent as the result of post-traumatic immobilization. They present with vague stretching pain felt at the end of range of those movements that stretch the ligament (see p. 168). Muscular lesions, mostly anteriorly, are described in clinical studies,21,22 on echography,23 in experiments in animals24,25 and in postmortem studies.26 Muscles, particularly their occipital insertions, can be strained during injury. The subsequent pain will be quite localized and can be elicited during either contraction or stretching – the contractile tissue pattern (see p. 169). The different parties involved in the approach to WAD are: • The patient who is seeking help and a refund of money. For most patients the two elements do not influence each other but for a number of people the compensation claim is essential. This may result in absence from work, illness behaviour, social disability, malingering and fraud.

Whiplash-associated disorders

Definition

Incidence

Classification

Pathology

Severe lesions

Other lesions

Discodural and discoradicular interactions

Facet joint problems

Ligamentous lesions

Muscular lesions

Medicolegal consequences

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Whiplash-associated disorders