Chapter 4

Wheelchair mobility

People with paraplegia. Most people with paraplegia rely solely on a manual wheelchair. They attain more advanced levels of wheelchair mobility than people with low levels of tetraplegia, and most can negotiate ramps and uneven ground with practice. Some that are young and agile can negotiate stairs, kerbs and grassy slopes, and can perform other difficult manouvres.1,2

Mobilizing with power wheelchairs

There are many types of mouth-, chin- and hand-control mechanisms which can be triggered in different ways.3 Control mechanisms can be electronically programmed to vary power-related features of the wheelchair including sensitivity, acceleration, cut-out and speed (see Chapter 13).4

The ability to control an electrical wheelchair also relies on correct positioning in the wheelchair. Patients with high levels of tetraplegia do not have the ability to reposition themselves and consequently are dependent on how others position them. Subtle changes in position, especially a change in the alignment of the arms or heads with respect to the control mechanism, can render a patient incapable of driving the wheelchair. Changes in position may occur if patients slide forwards on their cushions or if they are jolted or knocked while traversing bumpy ground. The trunk can also be pitched forwards when descending steep slopes.5 Chest or arm straps and moulded backrests can be used to help maintain an appropriate position. The tilt of the wheelchair and the angle of the backrest can also be manipulated to place patients in a less vertical and more stable position (see Chapter 13).

Mobilizing with manual wheelchairs

When patients first sit in manual wheelchairs they need to be taught basic skills such as how to apply and release the brakes, remove the arm rests and footplates, and turn the wheelchair. They can practise manoeuvring and reversing in tight spaces and negotiating around obstacles. There are also some simple tricks patients can be taught which are particularly important for those with tetraplegia and limited upper limb strength.1 For example, an arm placed on the wall can be used to help turn a corner (see Figure 4.1).

The wheelstand as the basis of advanced mobility

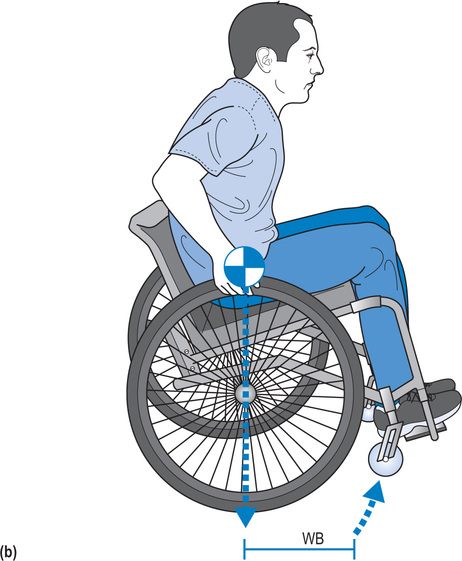

The wheelstand (also called a ‘wheelie’) is the basis of advanced wheelchair mobility.3 It involves rotating the wheelchair on its back axle so the front castors lift up off the ground (see Figure 4.2). The ability to perform this manoeuvre enables patients to descend grassy slopes, negotiate kerbs and small obstacles, and turn in tight spaces.

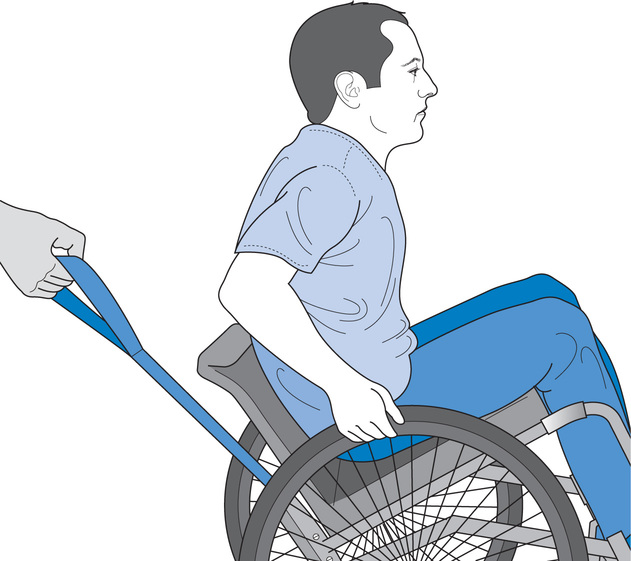

Training advanced wheelchair skills requires appropriate supervision to ensure patient safety. Physiotherapists must anticipate how patients may fall and position themselves appropriately to intervene if necessary. For example, patients are most likely to fall backwards when learning to descend a kerb backwards, and they are most likely to fall forwards when learning to ascend a kerb forwards. In both scenarios, physiotherapists need to stand at the kerb anticipating how the patient is most likely to fall and ready to provide assistance if necessary. Therapists need to guard against potential falls without interfering with the patient’s attempts at performing the wheelchair skill. A spotter training strap can be used for this purpose.6,7 The strap is attached to the under-frame of the wheelchair (see Figure 4.3). The physiotherapist holds one end of the strap, pulling on it if the wheelchair rotates too far backwards. This returns the wheelchair onto its four wheels, averting a backward fall. The physiotherapist still needs to stand close to the wheelchair so the weight of a backward-tipping wheelchair can be shared between the strap and the physiotherapist’s thigh. The spotter training strap can also be used when patients practise controlling a wheelchair down a slope. In this instance the strap is used as a breaking device in case the patient loses control of the wheelchair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree