CHAPTER 32 Vertebroplasty

SCREENING OF PATIENTS REFERRED FOR VERTEBROPLASTY

Before considering vertebroplasty, one must perform a through history, physical examination, and review appropriate investigations including radiographic analysis. This information should be able to differentiate between the source of pain being vertebral compression fracture or other back problems such as disc herniation, facet arthropathy, or spinal stenosis.1

History should include the site of pain, cause, inciting event, date of origin, exacerbating factors, alleviating factors, analgesic use, and activities of daily living. The patient should be screened for allergies, medications, medical problems, and conditions which may prevent the patient from lying prone during the procedure. The origin of pain may coincide with minor trauma and is typically exacerbated during activity, movement, or while weight bearing, and is relieved by lying down. Physical examination will reveal a tender site corresponding with the fracture level. If multiple vertebral compression fractures are present, the origin of pain will be elicited by careful clinical examination and analysis of radiographic studies.1,2 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful in patients with multiple fractures and usually reveals edema within the marrow space of the vertebral body that is best visualized on sagittal T2-weighted images. Bone scans can also differentiate the symptomatic level from incidentally discovered fractures.3 Bone scan imaging may be indicated when considering vertebroplasty therapy for patients suffering from multiple vertebral compression fractures of uncertain age or in patients with nonlocalizing pain patterns. We do not, however, routinely perform bone scans.4

Blood investigations should include complete blood and platelet counts, measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, International Normalized Ratio, activated clotting time, and complete metabolic panel.5,6

CONSULTATION

The time of reporting for the procedure, postprocedure care, and time of discharge from the hospital should be explained. Informed consent must include a through explanation of the procedure, methods, the physician’s prior history of complications, and the expected outcome based on the physician’s own outcome data. The patient should also be informed that the addition of material (barium, tungsten or tantalum) to make the bone cement material opaque technically makes the cement a non-FDA-approved material.1,7

Timing

Early studies performed vertebroplasty only after conventional treatment (medication and rest) had failed.8 Later series have advocated treatment as early as weeks or days if the patient requires narcotic medication or admission to hospital secondary to pain. Others have recommended vertebroplasty within 4 months.3 Although late treatment is unlikely to be successful, there are case reports of patients being successfully treated after a few years.9

Even though some believe it is a reasonable indication,1 there are insufficient data to categorically support the treatment of painful tumor infiltration without fracture. In addition, it is unclear whether to treat before or after radiation therapy. Injection of cement into the vertebral body will likely dislodge marrow elements that could potentially be absorbed into the blood stream. This concern for causing metastatic dissemination suggests that vertebroplasty should be performed only after radiation therapy.

Prophylactic vertebroplasty is neither widely accepted nor approved for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures and no studies have been done to substantiate the utility of this practice.1

TECHNIQUE

We do not give any prophylactic antibiotics and prescribe antibiotics postoperatively for a week.

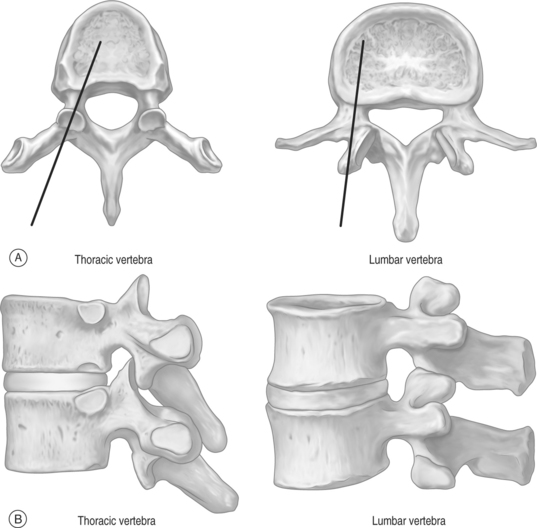

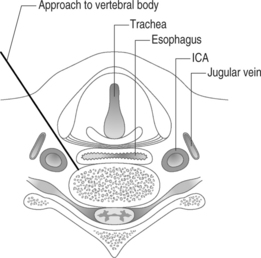

The thoracic and lumbar vertebral bodies are usually approached through one or, most commonly, both pedicles.2,8,21–27 Various approaches are used including a costovertebral,5 paravertebral, posterolateral, or anterolateral (cervical) approach. The parapedicular or transcostovertebral28 approach is used when a transpedicular approach cannot be used because of small pedicles, a fractured pedicle, or tumor invading the pedicle. Like most physicians, the authors prefer the transpedicular approach instead of the parapedicular approach, which may increase the chance of both a pneumothorax and that a paraspinous hematoma may not be controlled with application local pressure.6 The posterolateral approach increased the risk of injuring the exiting nerve root and segmental artery,6 and has largely been abandoned although some authors recommend it for lumbar vertebrae.20,23,28

There are many companies which supply cement and delivery equipment: Parallax Medical Inc./Arthrocare Corporation; Cook Group Inc.; Interpore Cross International Inc.; Interpore Cross International Inc./American OsteoMedix Corp.; Medtronic Inc./Medtronic Sofamor Danek; Orthofix International NV/Orthofix Inc.; Stryker Corp.; Tecres SPA.29 These sets contain stylets, needles, tubing, injectors, and injector barrels, but the end result is the same. The equipment allows one to inject cement into the anterior part of the vertebral body. Some authors have, however, modified the equipment and technique,30–33 and before these sets were available, operators recommended using 1 mL syringes for injection of cement.7,11,17,24

A small incision is made using a No. 11 knife blade and the introducer needle from the set is inserted (Fig. 32.4). A 15-gauge needle is used for cervical vertebrae and 10-gauge for thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.3 Currently, even thinner needles (13-gauge) are being used.6 The needle entry site is localized in the AP view. The authors use a diamond-tipped needle to start the entry.

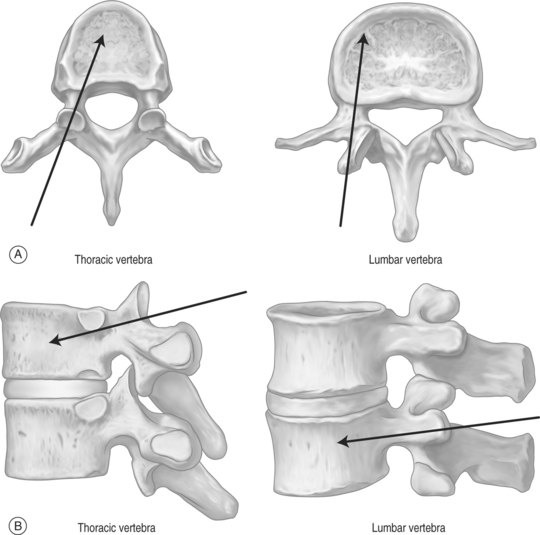

The needle is held with forceps to minimize radiation exposure to the operator.6 After confirming the position, the vertebroplasty needle is advanced through the superior-lateral cortex of the pedicle (Fig. 32.5). The vertical and horizontal diameter of the pedicle increases from upper thoracic to lower lumbar vertebrae (Table. 32.1). Proximally, in the sagittal plane, the direction of the pedicle is more oblique. (Fig. 32.6)

Table 32.1 Vertical and horizontal pedicle diameter

| Pedicles | T3 | L4 |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical diameter | 0.7 cm | 1.5 cm |

| Horizontal diameter | 0.7 cm | 1.6 cm |

The authors start with a diamond-tipped needle and then change it to beveled needle to make directional adjustments.7 The bevel of the needle is directed so that the tip is pointed laterally to avoid the spinal canal.

In osteoporotic bones it may be easy to advance the needle by hand, but in cases where the bone is dense, as in pathologic fractures, a mallet is necessary to advance the needle.6 While advancing the needle by hand the direction of needle may change, and using the mallet may keep the needle advancing in the direction wanted. We invariably use a mallet to advance the needle as this provides much greater control of the needle direction. As the needle is slowly advanced through the pedicle, we are hypervigilant about the location of the needle tip and the orientation of the needle. At no point do we want to breach the medial wall and subject the patient to the risk of cement extravasation into the spinal canal. When we reach the anterior part of the pedicle on lateral view, the trocar should be just lateral to the medial border of the pedicle on anteroposterior view. This ensures we are not going to break the medial wall of the pedicle. In addition, we do not want to fracture the roof or the base of the pedicle and inadvertently pierce an exiting nerve root. Advancing the needle through the lateral border of the pedicle will deposit cement intramuscularly. We have experienced this latter scenario on a few occasions and it is not associated with any adverse effects. Theoretically, it is conceivable that the needle could be placed too close to the aorta if the needle breaks through the lateral margin of the left pedicle, but this is a highly unlikely event. It is also important to be sure that the angle of inclination will allow the needle to ultimately rest in the anterior one-third of the vertebral body. To obtain ideal terminal position, it is critical that one repeatedly re-checks the cephalocaudal tilt while traversing through the pedicle. It is very difficult to re-orient the angle of inclination once the needle has passed through the pedicle and enters the vertebral body. If the angle of inclination is too steep then gentle downward pressure on the hub will minimize this angle, especially if the needle is still within the pedicle. We emphasize the term ‘gentle’ since osteoporotic bone can easily fracture if aggressive motions are used. If such gentle pressure does not achieve the intended result, a beveled needle can be substituted for the diamond-tipped needle. The bevel can be rotated so that the needle courses in the direction of choice. After the needle is observed to enter the vertebral body using a lateral view, the AP perspective does not need to be checked until the cement is injected. An AP view is needed at three points during the procedure: when planning where to insert he needle, checking the progress of the needle as it courses through the pedicle, and then later when cement is injected. Once the needle is in the vertebral body it should be rotated so that the tip is opening medially.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree