Chapter 24 Verapamil-Sensitive (Fascicular) Ventricular Tachycardia

Pathophysiology

The exact nature of the reentry circuit in verapamil-sensitive VT has provoked considerable interest. Some investigators have suggested that it is a microreentry circuit in the territory of the left posterior fascicle (LPF). Others have suggested that the circuit is confined to the Purkinje system, which is insulated from the underlying ventricular myocardium. False tendons or fibromuscular bands that extend from the posteroinferior LV to the basal septum have also been implicated in the anatomical substrate of this tachycardia. Less often, the reentry circuit is located in fibers distal to the left anterior fascicle (LAF) or may arise from fascicular locations high in the septum.1

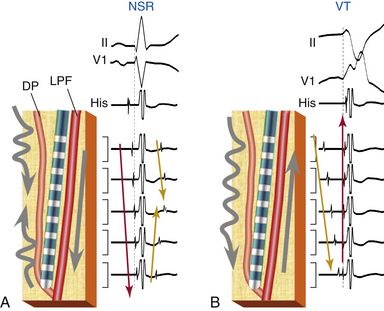

Currently, overwhelming evidence suggests that the VT is caused by a reentrant circuit incorporating the posterior Purkinje system with an excitable gap and a slow conduction area.2–4 The VT substrate can be a small macroreentrant circuit consisting of the LPF serving as one limb and abnormal Purkinje tissue with slow, decremental conduction serving as the other limb. The anterograde limb may be associated with longitudinal dissociation of the LPF or contiguous tissue that is directly coupled to the LPF (such as a false tendon) or, alternatively, has ventricular myocardium interposed. The zone of slow conduction appears to depend on the slow inward calcium current, because the degree of slowing of tachycardia CL in response to verapamil is entirely attributed to its negative dromotropic effects on the area of slow conduction.

The entrance site to the slow conduction zone is thought to be located closer to the base of the LV septum. From there, activation propagates anterogradely (from basal to apical along the LV septum) over the abnormal Purkinje tissue with decremental conduction properties and verapamil sensitivity, which serves as the anterograde limb of the circuit and appears to be insulated from the nearby ventricular myocardium. The lower turnaround point of the reentrant circuit is located in the lower third of the septum, where the wavefront captures the fast conduction Purkinje tissue from or contiguous to the LPF, and retrograde activation occurs over the LPF from the apical to basal septum forming the retrograde limb of the reentrant circuit. Also, at the lower turnaround point anterograde activation occurs down the septum to break through (at the exit of the tachycardia circuit) in the posterior septal myocardium below. The upper turnaround point of the reentrant circuit occurs over a zone of slow conduction located close to the main trunk of the left bundle branch (LB) in the basal interventricular septum (Fig. 24-1). The estimated distance between the entrance and exit of the circuit is approximately 2 cm.3,5

Clinical Considerations

Epidemiology

Age at presentation is typically 15 to 40 years (unusual after 55 years). Males are more commonly affected (60% to 80%). Verapamil-sensitive VT is the most common form of idiopathic LV VT, and it accounts for 10% to 15% of all idiopathic VTs.2,6

Clinical Presentation

Most patients present with mild to moderate symptoms of palpitations and lightheadedness. Occasionally, symptoms are debilitating, and include fatigue, dyspnea, and presyncope. Syncope and sudden cardiac death are very rare. The VT is typically paroxysmal and can last for minutes to hours. Although idiopathic LV VT can occur at rest, it is sensitive to catecholamines and often occurs during exercise, after exercise, or emotional distress. Occasionally, the VT can be incessant, may be sustained for a long period (days), and does not revert spontaneously to normal sinus rhythm (NSR). Patients with incessant tachycardia can develop cardiomyopathy.7 The clinical course is benign and the prognosis is excellent. Spontaneous remission of the VT may occur with time.

Principles of Management

Acute Management

Intravenous verapamil is typically successful in acutely terminating the VT. Termination with adenosine is rare, except for patients in whom isoproterenol is used for induction of the tachycardia in the EP laboratory.

Chronic Management

Long-term therapy with verapamil is useful in mild cases; however, it has little effect in patients with severe symptoms and the efficacy of oral verapamil in preventing tachycardia relapse is variable. Radiofrequency (RF) ablation is highly effective (success rate of 85% to 90%) and is recommended for patients with severe symptoms.2

Electrocardiographic Features

ECG during Ventricular Tachycardia

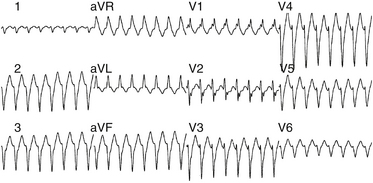

The QRS during VT typically has RBBB with LAF block configuration. The R/S ratio is less than 1 in leads V1 and V2 (Fig. 24-2).3 VTs arising more toward the middle at the region of the posterior papillary muscle have a left superior axis and RS in leads V5 and V6, whereas those arising closer to the apex have a right superior axis with a small “r” and deep S (or even QS) in leads V5 and V6. In contrast to VT associated with structural heart disease, the QRS duration during fascicular VT is relatively narrow (<140 to 150 milliseconds), and the RS interval (the duration from the beginning of the QRS to the nadir of the S wave) in the precordial leads is relatively short (60 to 80 milliseconds); thus, the VT is frequently called “fascicular” VT. The VT rate is approximately 150 to 200 beats/min (range, 120 to 250 beats/min). Alternans in the CL is frequently noted during the VT; otherwise, the VT rate is stable.

Fascicular VT can be classified into three subtypes: (1) left posterior fascicular VT with an RBBB and superior axis configuration (common form); (2) left anterior fascicular VT with RBBB and right-axis deviation configuration (uncommon form); and (3) upper septal fascicular VT with a narrow QRS and normal axis configuration (rare form).1

Electrophysiological Testing

Tachycardia Features

Site of Earliest Ventricular Activation

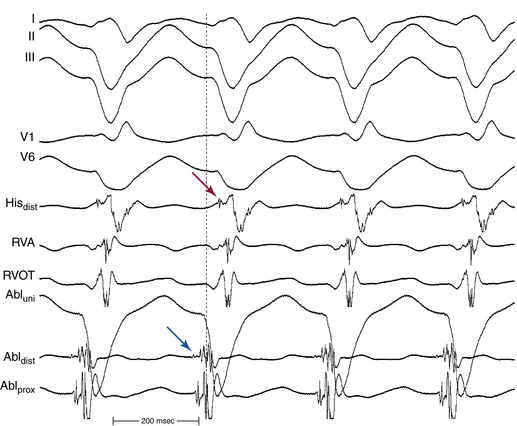

The site of earliest ventricular activation during VT (which represents the exit of the reentrant circuit) is in the region of the LPF (inferoposterior LV septum) in 90% to 95% of LV VTs (explaining the RBBB–superior axis configuration of the QRS), and in the region of the LAF (anterosuperior LV septum) in 5% to 10% of LV VTs (explaining the RBBB–right axis configuration of the QRS). In most cases, ventricular electrograms are discrete during both NSR and VT. The His bundle (HB) is not a component of the reentrant circuit, because a retrograde His potential is often recorded 20 to 40 milliseconds after the earliest ventricular activation (Fig. 24-3).

Purkinje Potential

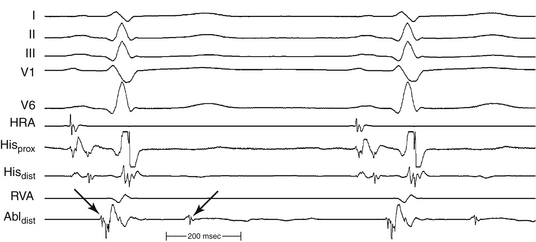

The Purkinje potential (PP or P2) is a discrete, high-frequency potential that precedes the site of earliest ventricular activation by 15 to 42 milliseconds and is recorded in the posterior third of the LV septum during VT and NSR (Fig. 24-4; see also Fig. 24-3).3,4 Because this potential also precedes ventricular activation during NSR, it is believed to originate from activation of a segment of the LPF, and to represent the lower turnaround point in the reentrant circuit. The earliest ventricular activation site (exit) during VT is identified more apically in the septum than the region with the earliest recorded PP.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree