Valgus Extension Overload

James R. Andrews MD

Reneé S. Riley MD

History of the Technique

Bennett,1 in 1941, described elbow pathology he had noted in baseball pitchers, reporting loose bodies and osteophytes of the coronoid and olecranon tip. He anecdotally reported that removal relieved symptoms and allowed return to play. The spectrum of symptoms and pathology associated with valgus extension overload of the elbow was described by Waris2 in 1946 in his article on 17 elite javelin throwers. He described the debilitating posteromedial elbow pain sometimes associated with loss of extension, which required between 4 weeks and 1 year of rest before return to play. He reported radiographic changes in the olecranon in 12 of 17 cases. He concluded that these changes were due to the repetitive trauma of throwing.

Slocum,3 in 1968, classified elbow injuries into three categories: medial tension overload, lateral compression overload, and extension overload. He concluded that the combination of these in the baseball pitcher led to the excessive wear in the joint.

King et al.,4 in 1969, reported on a series of 50 professional baseball pitchers and noted a 50% incidence of elbow flexion contracture. They coined the term “medial elbow stress syndrome” and noted attenuated medial structures leading to the compression of the lateral compartment and loose body formation. They also noted loose bodies posteriorly, but hypothesized that this was not due to the force of hyperextension jamming the olecranon into its fossa, because of the high incidence of flexion contracture in pitchers. Rather, they thought that the valgus stress was the culprit, leading to impingement of the medial aspect of the olecranon against the wall of the olecranon fossa.

Indelicato et al.,5 in 1979, reported that 20 out of 25 professional baseball pitchers were able to return to competitive throwing following open excision of osteophytes and removal of loose bodies through a medial approach. Wilson et al.,6 in 1983, coined the term “valgus extension overload” and reported on five pitchers who underwent excision of posteromedial osteophytes through a posterolateral approach, and all returned to their previous level of competition.

With the advent of elbow arthroscopy, open treatment of valgus extension overload is primarily of historic interest, except in cases where arthroscopy is contraindicated or when another open procedure is being performed (e.g., ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction). Andrews and Timmerman,7 in 1995, reported on 72 professional baseball players who underwent elbow surgery. Sixty-eight percent of those treated with arthroscopic excision of posteromedial olecranon osteophytes returned to the same or higher level of competition.

Reddy et al.,8 in 2000, reported that posterior olecranon impingement was the most common diagnosis in 187 elbow arthroscopies performed at the Kerlan-Jobe Clinic from 1991–1997. They noted that 92% of the patients contacted rated their results as good or excellent at an average of 42 months follow-up, and 85% of professional athletes returned to their previous level of competition. There was no mention, however, of the reoperation rate in this patient population.

Indications and Contraindications

Valgus extension overload describes a constellation of pathologies in the elbow of the throwing athlete as a result of the repetitive forces exerted during the throwing motion. Medial compartment distraction is accompanied by lateral compartment compression and posterior compartment impingement. The most common presentation is pain secondary to impingement of the posteromedial olecranon tip and the medial aspect

if the trochlea, sometimes associated with loss of extension due to osteophyte formation. Valgus extension overload can also be present with changes in the lateral compartment due to compressive forces. Loose bodies can cause painful catching and locking. The throwing athlete will often complain of pain with ball release as well as diminished velocity or loss of ball control, usually with early release and high pitches.9

if the trochlea, sometimes associated with loss of extension due to osteophyte formation. Valgus extension overload can also be present with changes in the lateral compartment due to compressive forces. Loose bodies can cause painful catching and locking. The throwing athlete will often complain of pain with ball release as well as diminished velocity or loss of ball control, usually with early release and high pitches.9

On physical examination, flexion contracture is a common finding, but it is not necessarily pathologic in the throwing athlete. The valgus extension overload test is performed by repeatedly forcing the elbow from slight flexion rapidly into extension while applying a valgus stress. This should reproduce pain in the posteromedial aspect of the elbow from impingement of the posteromedial olecranon tip on the medial wall of the olecranon fossa. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, this is associated with valgus overload with or without instability, and forced hyperextension. Radiographs may show the olecranon osteophyte or loose bodies. A posterior osteophyte may be seen on a routine lateral view. The best view for showing the posteromedial osteophyte is an oblique axial view with the elbow flexed to 110 degrees (Fig. 24-1), although it is not always visualized on radiographs.

Indications for surgery include the clinical history and physical exam findings described above with or without radiographic evidence of osteophyte formation. The athlete should have failed a course of nonoperative management and be unable to throw effectively due to posteromedial elbow pain or locking from loose bodies. Conservative treatment in the face of a posteromedial olecranon osteophyte has not had a high success rate in our experience; but in general, we do recommend a 6-week period of rest and strengthening exercises, including a rotator cuff protocol, followed by an interval throwing program. This is beneficial for overall general conditioning and improves results postoperatively if surgery is required.6 Often, the surgical procedure can be delayed until the end of the season, depending on whether the athlete is able to tolerate the symptoms and to play effectively.

Fig. 24-1. Axial view of the elbow showing articulation of olecranon with trochlea and posteromedial olecranon osteophyte on profile. |

Contraindications to surgical treatment with arthroscopy include any condition that does not allow distention of the joint or access to the joint otherwise, such as bony or fibrous ankylosis. Also, conditions that place the neurovascular structures at increased risk for injury are relative contraindications. These include previous ulnar nerve transposition, which precludes the use of an anteromedial portal, and severe deformities, which distort anatomy, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Any condition that increases the risk for infection, such as cellulitis of the overlying skin, is a contraindication.

Surgical Techniques

Anesthesia

General anesthesia is commonly used for elbow arthroscopy for several reasons. It provides complete muscle relaxation and is most comfortable for the patient. It also allows for a reliable neurovascular exam immediately following the procedure, which is important because most of these operations are performed on an outpatient basis and prolonged observation is not feasible. Some surgeons advocate the use of intravenous regional anesthesia, but we do not recommend its use for the above reason and because the use of a double tourniquet can compromise exposure.

Patient positioning is very important during elbow arthroscopy to ensure adequate visualization of the joint. We use the supine position (Fig. 24-2) because of the ease of general anesthesia and conversion to an open procedure, if necessary. It is our opinion that the structures are in a more anatomic orientation in this position as well. Other alternatives include the prone and lateral decubitus positions.

Surface Anatomy

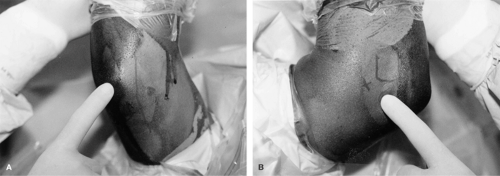

The identification of palpable surface structures about the elbow is crucial prior to arthroscopy. A marking pen should be used to outline the medial and lateral epicondyles, which should be easily palpated. The radial head can be identified by supinating and pronating the forearm. The olecranon tip is subcutaneous and should be marked as well (Fig. 24-3A,B). The ulnar nerve can be felt just posterior to the medial epicondyle. It is crucial to make sure that the nerve does not sublux anteriorly and to review the surgical history to confirm that the nerve has not been transferred during a previous procedure.

Anterolateral Portal

The anterolateral portal is established after the joint is distended by injecting saline into the lateral soft spot. The anterolateral portal is located in a different “soft spot” approximately 2 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the lateral humeral epicondyle. A spinal needle is placed first to ensure egress of fluid before making the skin incision. The incision is superficial, and a hemostat is used to spread the soft tissues. Care must be taken to avoid the cutaneous nerves in the region, including the lateral antebrachial and the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerves. To establish the anterolateral portal, the blunt trocar and sheath for a 4.0-mm 30-degree arthroscope are inserted into the portal site. An assistant should apply pressure to the syringe, injecting saline into the lateral soft spot. This will distend the joint and move the neurovascular structures away from the capsule. The trocar should be directed toward the center of the elbow, and the capsule is trapped against the distal humerus and then punctured to enter the joint. This is necessary to avoid damage to the anterior neurovascular structures. The radial nerve is also at risk, and the arthroscope may pass from 4 mm to 7 mm posterior to it. This distance is closer to 7 mm when the joint is distended.

Fig. 24-3. A: Medial side of the elbow, with structures marked, including olecranon tip, medial epicondyle, and ulnar nerve. B: Lateral side of the elbow with structures marked, including the radial head and lateral epicondyle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|