Vacuum-Assisted Closure in Extremity Trauma

Anthony J. DeFranzo

Louis C. Argenta

Indications/Contraindications

Wounds of the upper and lower extremities provide a constant challenge for orthopaedic and plastic surgeons. Complex severe injuries involving bone and soft tissue demand major reconstructive procedures. Less severe injuries exposing tendon, bone, and joints also demand innovative surgical approaches. Many patients with injured extremities have been the victim of multiple traumas and may have major associated injuries involving head, chest, and abdomen. Major blood loss, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), high intracranial pressure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septicemia, and renal failure frequently complicate the treatment of these patients. Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) has provided a way to effectively manage these wounds until definitive reconstruction can be performed. Vacuum-assisted closure has also greatly simplified reconstruction in many of these patients. Skin grafts are performed in many cases that would have otherwise required major rotational flaps or free flaps prior to the advent of VAC therapy.

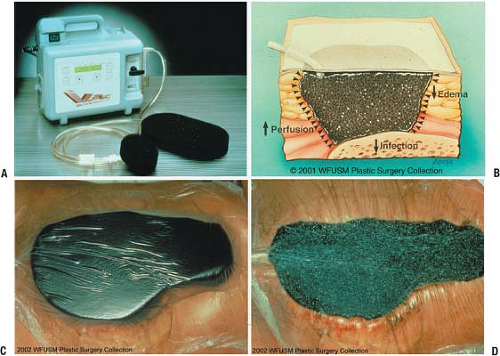

The mechanics of the VAC system are straightforward. The system consists of an open cell polyurethane ether foam sponge sealed by an adhesive drape. All pores in the sponge communicate so that negative pressure applied to the sponge is applied equally and completely to the entire wound surface. The effects of the VAC on the wound are multiple. The application of negative pressure causes the sponge to collapse toward its center. Traction forces are thus applied to the wound perimeter pulling the wound edges together progressively making the wound smaller. The VAC sponge should be cut to fit inside the wound to maximize traction forces on the wound edges. The sponge should not overlap intact skin, as skin maceration may occur. In addition, the VAC removes wound edema, appears to increase circulation and decrease bacterial counts, and significantly increases the rate of granulation tissue formation (1,6).

All wounds are thoroughly debrided prior to VAC placement. No clinical infection, purulence, or suspected osteomyelitis should be present prior to VAC placement. Grossly contaminated wounds are a contraindication for VAC placement. The VAC sponge should not be applied directly over major exposed blood vessels in the extremity status posttrauma, especially if the vessel wall has been damaged or a vessel repair has been performed. A protective interface such as Adapticw may be used. Exposed, repaired, or damaged major vessels should be covered with flaps such as muscle flaps or fasciocutaneous flaps. The VAC may be applied over intact nerves if muscle flap or adequate soft tissue coverage is not possible. A layer of Adaptic may help prevent pain caused by VAC traction especially when VAC sponges are changed. Nerve repairs should also be protected by an interface layer such as Adaptic placed under the VAC sponge. Adequate soft tissue or flap coverage of major peripheral nerves is preferred for final long-term management. The VAC may frequently allow secondary closure of wounds over major peripheral vessels or nerves by pulling together adequate soft tissue as edema is removed. Split-thickness skin grafts placed directly over major exposed vessels or nerves is possible with VAC therapy after granulation tissue occurs, but not preferred.

The VAC sponge may be placed directly on bone if the bone surface bleeds following sharp debridement by an osteotome or low-speed power burr. Occasionally, desiccation of bone may occur

with the VAC. If desiccation occurs, further debridement to punctuate bone surface bleeding with the immediate placement of Integraw Dermal Regeneration Template and then VAC placement directly over Integra may be tried. This technique has provided Integra take over bone allowing subsequent skin graft coverage. The Integra must be meshed or holes cut in the outer silicone layer before VAC sponge placement. Relatively small areas of bone have been successfully treated in this manner. Large areas of exposed bone are better treated with pedicle muscle flaps, pedicle fasciocutaneous flaps, or free flaps. The VAC should not be placed over desiccated bone with questionable viability without punctuate bone surface bleeding.

with the VAC. If desiccation occurs, further debridement to punctuate bone surface bleeding with the immediate placement of Integraw Dermal Regeneration Template and then VAC placement directly over Integra may be tried. This technique has provided Integra take over bone allowing subsequent skin graft coverage. The Integra must be meshed or holes cut in the outer silicone layer before VAC sponge placement. Relatively small areas of bone have been successfully treated in this manner. Large areas of exposed bone are better treated with pedicle muscle flaps, pedicle fasciocutaneous flaps, or free flaps. The VAC should not be placed over desiccated bone with questionable viability without punctuate bone surface bleeding.

Preoperative Planning

Wounds should be thoroughly debrided before VAC application. Once the wounds are clean, VAC therapy may be initiated. VAC sponges can initially be applied in the operating room following definitive debridement.

Surgery

To illustrate the application of the VAC device to wounds of the extremities, case studies will be shown to illustrate degloving injuries, gunshot wounds, and a variety of avulsion injuries with exposed tendons, bones, and joints. VAC treatment of traumatic wound complications such as infection and hematoma is also illustrated.

Degloving Injuries

Several degloving injuries to the hand have been treated by the VAC with varying results from 0% to 95% take of replaced degloved skin. The degree of take depends on the condition of the degloved skin and the viability of underlying tissue. The degloved skin is frequently crushed and lacerated. It may be difficult to clinically assess the viability of the degloved avascular skin. Also, roller injuries which frequently cause degloving injuries of the hand may crush as well as deglove the hand. Contusion to the hand intrinsic muscle and crush injury of blood vessels in the hand may also be difficult to evaluate. Progressive loss of viability may occur.

In all hand degloving injuries (N = 6) treated to date at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, fingers were not viable significantly beyond the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints and amputations were made at or just distal to that level (4). The thumb has been salvaged at full length in one case. In degloving injuries, most extensor and flexor tendons remain on the hand. If the distal phalanx is avulsed with the skin envelope the flexor digitorum profundus tendon(s) may also be avulsed from the hand and even from the forearm. Extensor peritenon and flexor tendon sheaths are frequently intact, providing vascularized coverage to the tendon.

The clinical approach has been to assess viability of the degloved skin and hand after meticulous debridement and completing the amputations at the appropriate level. The skin is thoroughly defatted, pie-crusted, and placed back on the hand with a few staples and/or sutures. The VAC is then immediately applied. The sponge is cut to fit over the grafted, degloved skin, using one or multiple contiguous pieces of sponge. A “hand VAC” kit is also commercially available. Controlled suction of 125 mm Hg pressure is applied (Fig. 4-1). This procedure takes very little operative time. If successful, the patient is spared a great deal of overall treatment time and morbidity compared to more complicated methods of reconstruction. Therefore, with a degloving injury, our treatment algorithm is as follows: (a) skin defatting and debridement, (b) wound debrideded, (c) skin applied to wound, (d) VAC applied to wound. The VAC is left in place for 4 to 6 days. If there are areas which have not revascularized, the VAC may be replaced for 2 more days for a total of 6 days. After day 6, further take with VAC therapy does not seem to occur and we have not used the VAC longer than 6 days.

If VAC therapy is totally unsuccessful, no more than 6 days are lost with the attempt at degloved skin replacement before other methods of reconstruction are initiated. The best case to date of VAC replacement of degloved skin achieved a 95% take of avulsed skin with preservation of fingers at or just distal to the PIP joints and preservation of the thumb at full length. Excellent range of motion of the metacarpal phalangeal joints was achieved. Further surgery involved outpatient revision of the amputations of the four amputated fingertips and deepening of the first web space (Fig. 4-2).

FIGURE 4-2 Degloving injury to the hand. A: Entire dorsum and all fingers avulsed to distal palm. Neurovascular bundles present to or just beyond proximal interphalangeal joints. Extensor paratenon intact; flexor tendon sheaths intact. B:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|