Chapter 211 Urticaria

Diagnostic Summary

Diagnostic Summary

• Urticaria (hives): Well-circumscribed erythematous wheals with raised serpiginous borders and blanched centers that may coalesce to become giant wheals; limited to the superficial portion of the dermis.

• Angioedema: Eruptions similar to those of urticaria but with larger well-demarcated edematous areas that involve subcutaneous structures as well as the dermis.

• Chronic versus acute: Recurrent episodes of urticaria and/or angioedema of less than 6 weeks’ duration are considered acute, whereas attacks persisting beyond this period are designated chronic. When no underlying cause is found, chronic urticaria is referred to as chronic idiopathic urticaria.

• Special forms: Special forms have characteristic features—dermographism, cholinergic urticaria, solar urticaria, cold urticaria.

Introduction

Introduction

Urticaria and angioedema are relatively common conditions: It is estimated that they occur in 15% to 25% of the general population.1 Although persons in any age group may experience acute or chronic urticaria and/or angioedema, young adults (postadolescence through the third decade of life) are most often affected.2,3

The basic pathophysiology of urticaria involves the release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells or basophilic leukocytes, both of which have high-affinity receptors for immunoglobulin E (Ig E).4 Although this inflammation classically occurs as a result of IgE–antigen complexes interacting with these cells, other non–IgE-mediated mechanisms are probably also critical in many patients with urticaria, including prostaglandins, leukotrienes, cytokines and chemokines. A growing body of evidence shows that at least 40% of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria have clinically relevant functional autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor on basophils and mast cells. The term autoimmune urticaria is used for this subgroup of patients presenting with continuous ordinary urticaria.5

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

The signs and symptoms of acute and chronic urticaria show consistent patterns despite the many diverse etiologic and initiating factors (see later) that have been found, yet the pathogenesis cannot be entirely ascribed to any one mechanism. However, at present, it appears that mast cells and mast cell–dependent mediators play the most prominent role in the pathogenesis of urticaria.6

Mast cells are widely distributed throughout the body and are found primarily near small blood vessels, particularly in the skin. The granule-containing mast cell is a secretory cell capable of releasing both preformed and newly synthesized molecules, termed mediators. These mediators (listed in Box 211-1) play key roles in the pathogenesis of both immunologic and nonimmunologic inflammatory reactions. The three distinct sources of mediators are as follows:

• Preformed mediators, which are contained in the granules and are released immediately

• Secondarily formed mediators, which are generated immediately or within minutes by the interaction of the primary mediators and nearby cells and tissues

• Granule matrix–derived mediators, which are preformed but slowly dissociate from the granule after discharge and remain in the tissues for hours

BOX 211-1 Mast Cell–Derived Mediators

• Eosinophil chemotactic factors of anaphylaxis (ECF-A)

• Eosinophil chemotactic oligopeptides

• Neutrophil chemotactic factor

• Exoglycosidases (β-hexosaminidase, β-δ-galactosidase,* β-glucuronidase)

• Slow-reacting substances (SRS-A): leukotrienes (LT) C, LTD, LTE

• Monohydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs)

• Hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs)

• Platelet-activating factor (PAF)*

Preformed, granule-associated:

Data from Keahey TM. The pathogenesis of urticaria. Dermatol Clin 1985;3:13-28.

The most common immunologic mechanism is mediated by IgE.

Helicobacter pylori has been implicated as a causative agent in chronic urticaria. However, two reviews of the trials showing the benefit of H. pylori eradication in patients with chronic urticaria have arrived at conflicting conclusions, one saying the benefit is weak and another that it is statistically significant.7,8 Including testing for H. pylori seems reasonable; if positive, a decision to proceed with this management should be considered carefully in the context of relative harms/burdens and benefits as well as patient values and preferences.

Causes of Urticaria

Causes of Urticaria

Fundamental to the treatment of urticaria is the recognition and control of causative factors.

Physical Urticarias

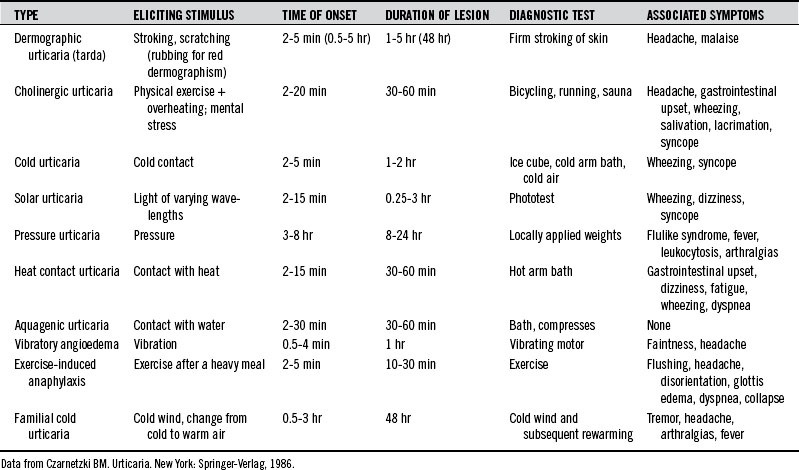

Urticaria can be produced as a result of reactions to various physical stimuli. The most common forms of physical urticarias are dermographic, cholinergic, and cold urticarias (Table 211-1). These are briefly described here. Less common types of physical urticarias or angioedema are as follows2:

Cholinergic Urticaria

A variety of systemic symptoms may also occur, suggesting a more generalized mast cell release of the mediators than in the skin. Headache, periorbital edema, lacrimation, and burning of the eyes are common symptoms. Less common symptoms are nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, dizziness, hypotension, and asthma attacks.2

Cold Urticaria

Cold urticaria is an urticarial and/or angioedematous reaction of the skin when it comes into contact with cold objects, water, or air. Lesions are usually restricted to the area of exposure and develop within a few seconds to minutes after the removal of the cold object and rewarming of the skin. The lower the object’s or element’s temperature, the faster the reaction. Children with cold urticaria have a higher risk of anaphylaxis, especially triggered by swimming.9

Widespread local exposure and generalized urticaria can be accompanied by the following symptoms:

Cold urticaria has been observed to accompany a variety of clinical conditions, including the following1:

The association of cold urticaria with infectious mononucleosis is well established. Other conditions associated with cold urticaria are cryoglobulinemia and myeloma, in which cold urticaria may precede the diagnosis by several years.2

Autoimmune Urticaria

Although much remains unknown regarding the specific pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying most cases of chronic urticaria, a minority seem to have an autoimmune basis. Research has discovered that a significant percentage of patients previously categorized as having idiopathic urticaria have autoantibodies to IgE or the FcεRIα subunit of the high-affinity IgE mast cell receptor.10 Studies have identified these autoantibodies in 24% to 76% of patients with chronic urticaria. From a clinical perspective, these patients tend to have a somewhat more severe, prolonged course of disease. Middle-aged women are disproportionately represented in the population of patients with urticaria, and higher rates of autoimmunity in this group, particularly for thyroid disease, may account for this preponderance. Thyroid autoantibodies are found more frequently in patients with these IgE receptor autoantibodies (see later discussion of thyroid).

Autoimmune diseases are well known to be associated with bowel permeabilities.11–14 Because subclinical impairments of small bowel enterocyte function have been postulated to induce a higher sensitivity to histamine in the digestive tract,15 it makes sense from a naturopathic standpoint to treat overt and subclinical digestive system permeabilities to decrease systemic inflammatory responses to endotoxins in these autoimmune conditions.

Drugs

Drugs make up the leading cause of urticarial reactions in adults. In children, the reactions are usually due to foods, food additives, or infections.2

Most drugs are composed of small molecules incapable of inducing antigenic/allergenic activity on their own. Typically, they act as haptens that bind to endogenous macromolecules, ultimately causing the production of hapten-specific antibodies. Alternatively, drugs can interact directly with mast cells to induce degranulation. Many drugs have been shown to produce urticaria. Box 211-2 provides a condensed list.16 The two most common urticaria-inducing drugs, penicillin and aspirin, are briefly discussed here.

BOX 211-2 Drugs That Can Cause Urticaria

Data from Andrews GC. Andrews’ diseases of the skin, ed 7. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1982:131.

Penicillin

Antibiotics, including penicillin and related compounds, are the most common cause of drug-induced urticaria. The allergenicity of penicillin in the general population is thought to be at least 10%. Nearly 25% of these individuals display urticaria, angioedema, or anaphylaxis on ingestion of penicillin.2,17

An important characteristic of penicillin is that it cannot be destroyed by boiling or steam distillation. This is a problem because penicillin and related contaminants can exist undetected in foods. To what degree penicillin in the food supply contributes to urticarial reactions is not known. However, urticaria and anaphylactic symptoms have been traced to penicillin in milk,18 soft drinks,19 and frozen dinners.20 In one study of 245 patients with chronic urticaria, 24% had positive skin test results and 12% had positive results on the radioallergosorbent test for penicillin sensitivity.21 Of those 42 patients sensitive to penicillin, 22 experienced clinical improvement with a dairy-free diet, whereas only 2 out of 40 patients with negative skin test results experienced improvement with the same diet. This study would seem to provide indirect evidence of the importance of penicillin in the food supply in urticaria.

In an attempt to provide direct evidence, penicillin-contaminated pork was given to penicillin-allergic volunteers. No significant reactions were noted other than transient pruritus in two volunteers.22 Penicillin in milk appears to be more allergenic than penicillin in meat.18 Presumably the reason is that penicillin can be degraded into more allergenic compounds in the presence of carbohydrate and metals, suggesting that penicillin in milk may be more allergenic than artificially contaminated meat.18

Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

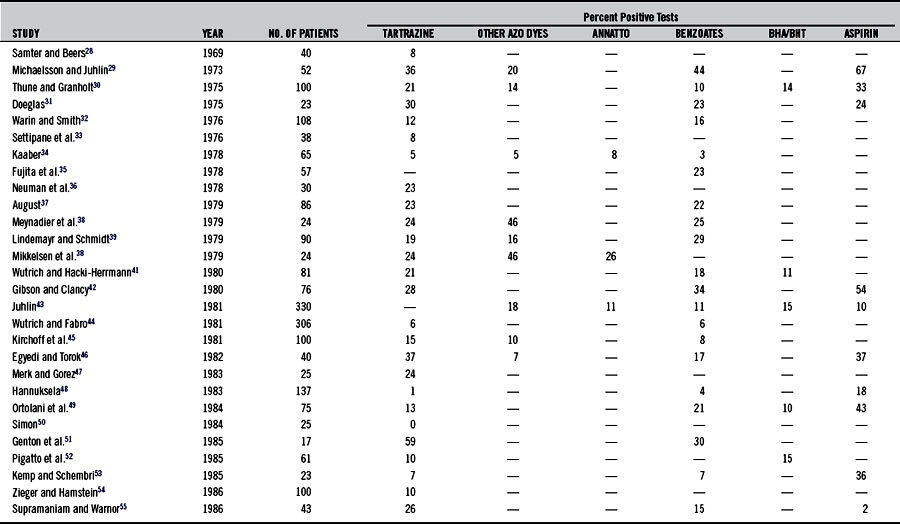

Urticaria is a more common indicator of aspirin sensitivity than is asthma (see Chapter 147). The incidence of aspirin sensitivity in patients with chronic urticaria is at least 20 times greater than that in normal controls.23–27 Studies (summarized in Table 211-2)28–57 have demonstrated that 2% to 67% of patients with chronic urticaria are sensitive to aspirin.

Aspirin inhibition of cyclooxygenase apparently shunts eicosanoid metabolism toward leukotriene synthesis, thereby increasing smooth muscle contraction and vascular permeability. In addition, aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to increase gut permeability dramatically and may alter the normal handling of antigens.53,58 NSAIDs are also known be associated with prolonged and more pronounced autoreactivity in urticaria.57 The daily administration of 650 mg of aspirin for 3 weeks has been shown to desensitize patients with urticaria and aspirin sensitivity. While taking the aspirin, patients also became nonresponsive to foods to which they usually reacted, such as pineapple, milk, egg, cheese, fish, chocolate, pork, strawberries, and plums.59 Others have noted this effect in patients with asthma, but they have also found that the effect disappears within 9 days after the treatment is stopped, suggesting the loss of effect or a possible placebo response.60

Food-Related Causes

Food Allergy

IgE-mediated urticaria can occur on the ingestion of a specific reaginic antigen. Although any food can be the agent, the most common offenders are milk, fish, meat, eggs, beans, and nuts.2,17,61–67 Other allergens are citrus, kiwis, peanuts, and apples.61 Individuals with atopy are most likely to experience urticaria as a result of IgE-related mechanisms, although reports confirm the presence of pseudoallergic reactions, whereby direct mast cell histamine release is involved in this reactivity. Aromatic volatile ingredients in tomatoes, wine, and culinary herbs (basil, fenugreek, cumin, dill, ginger, coriander, caraway, turmeric, parsley, pepper, rosemary, and thyme) have been considered the initiating factors in some of these non-IgE events.68,69

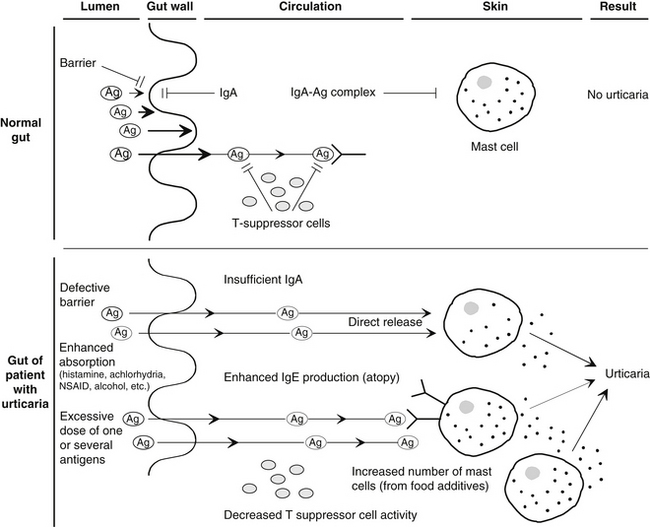

Food allergies may contribute greatly to the increased permeability of the gut in urticaria. A basic requirement for the development of a food allergy is the absorption of the allergen through the intestinal barrier. Several factors are known to significantly increase gut permeability, including alcohol, NSAIDs, vasoactive amines ingested in foods or produced by bacterial action on essential amino acids, and possibly many food additives (see Chapter 20 for a full discussion). Gut permeabilities are also associated with autoimmune conditions.11–14 Because chronic urticaria is now known to be at least partially related to an autoimmune process (see earlier discussion of autoimmune urticaria), it is possible that, depending on the genetic susceptibility of individual, these bowel permeabilities may play a key role in the instigation of immune activity and its prolongation, leading to chronic urticaria.

In addition, several investigators have reported alterations in gastric acidity, intestinal motility, and the function of the small intestine and biliary tract in up to 85% of patients with chronic urticaria.70–74 Selective IgA deficiency, gastroenteritis, hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria, and other disruptive factors reported in patients with chronic urticaria may temporarily or permanently alter the barrier and immune function of the gut wall, predisposing an individual to allergic sensitization.

In one study of 77 patients with chronic urticaria, 24 (31%) were diagnosed as achlorhydric and 41 (53%) were shown to be hypochlorhydric.72 Treatment with hydrochloric acid and a vitamin B complex gave impressive clinical results, highlighting the importance of correcting any underlying factor in the treatment of chronic urticaria (see Chapter 24).

Although IgE-mediated reactions are thought to predominate in immunologic urticaria, it has been suggested that IgG-mediated reactions are probably responsible for the majority of adverse reactions to foods, as seen in general practice (see Chapter 54). IgG antigen-antibody complexes are capable of promoting complement activation and the subsequent generation of anaphylatoxins that promote mast cell degranulation. This could be a significant factor in some cases of urticaria.

Figure 211-1 summarizes the basic aspects of a hypothetical model of immune defense in the normal gut and the urticarial gut.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree