The interaction between the health care team and the patient to achieve the goal of prosthetic restoration and rehabilitation is referred to as prosthetic management (

27). The process of prosthetic rehabilitation can be organized into a four-phase

process: preprosthetic management, postoperative care, prosthetic fitting and training, and long-term follow-up care. This staging permits the rehabilitation physician to assess the individual with an amputation and organize the rehabilitation program.

Preprosthetic Patient Evaluation and Management

Preprosthetic management begins when the decision to perform an amputation is made, when a patient is initially evaluated after a traumatic amputation, or when a child is born with a congenital skeletal deficiency. It ends with the fitting of a prosthesis. Optimal care is ensured when members of the prosthetic team can evaluate the patient before amputation, but often the events surrounding an amputation delay the rehabilitation assessment until the postoperative period.

The preprosthetic evaluation, whether performed preoperatively or postoperatively, should focus on identifying factors that will affect the ultimate functional status of the patient and optimize prosthetic fitting. Issues that need evaluation include assessing the premorbid functional status, identifying coexisting musculoskeletal, neurologic, and cardiopulmonary disease that will influence the rehabilitation potential, determining the available social support network, and understanding the patient’s goals and expectations. Education of the patient and family about the functional consequences of amputation and the steps involved in prosthetic rehabilitation will help allay some of the fears the patient may have about his or her future. Therapy programs for range of motion, conditioning exercises, correct positioning of the residual limb, ambulation with gait aids, relaxation techniques, and activities of daily living (ADLs) should be started as soon as medically appropriate. The patient is often better able to absorb and comply with a therapy program during the preoperative period than during the early postoperative period, when incisional pain, medication, or apprehension may interfere with the ability to participate.

Postoperative Care

The goals that direct the postoperative, preprosthetic management of the individual with an amputation are outlined in

Table 74-2. During the immediate postoperative period, general medical care focuses on optimizing control of underlying disorders that can interfere with rehabilitation: diabetes, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, renal disease. Maintaining nutritional status is frequently neglected, nevertheless it plays a critical role in ensuring wound healing (

8) and in facilitating the muscular strength adaptations needed for prosthetic mobility. The principles guiding residual limb care are based on ensuring primary wound healing, controlling pain, minimizing edema, and preventing contractures.

Options for wound management include soft dressings, semi-rigid dressings (Unna casts), rigid dressings (plaster or fiberglass casts), and air splints. Each option has advantages and disadvantages. Soft dressings are typically used with an elastic bandage wrap (i.e., Ace bandage) or a compressive stockinette. Soft dressings have the advantage of being readily available, quickly applied, and allowing frequent wound inspection. However, they do not provide protection from external trauma and only have a limited ability to control edema. If poorly applied, elastic wraps can lead to tourniquet effect. Elastic bandages require considerable cooperation, skill, and attention on the part of the patient, family, and medical staff because the wraps need to be reapplied frequently and carefully to be successful. In practice their use is problematic enough and alternatives such as compressive stockinettes, elastic stump shrinkers, or roll-on gel liners are often a better choice of edema management. Despite a number of limitations, soft dressings remain the most commonly used wound care approach following amputation (

28).

Rigid dressings have been reported to reduce wound-healing time and lead to more rapid and improved rehabilitation (

29,

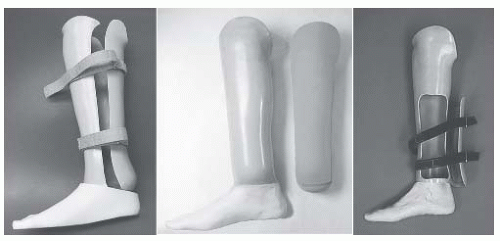

30). The primary concerns surrounding rigid dressings are the inability to inspect the wound and the potential increase in wound breakdown from incorrect application or early weight bearing in dysvascular individuals with an amputation. In spite of these limitations, postoperative rigid dressings may be the preferred method of wound care, especially for the transtibial individual with an amputation, but their clinical use and acceptance has been limited by the lack of expertise in their application. Rigid dressings can be fabricated in a removable form that resembles a transtibial prosthetic socket or as a nonremovable cast that extends to the mid-thigh level. The rigid dressing is most commonly made using standard orthopedic cast materials but commercially available prefabricated devices are also available. A nonremovable rigid dressing is typically applied during or shortly after surgery and replaced every 7 to 14 days. The mid-thigh length of the dressing prevents knee flexion contractures and is continued until adequate wound healing has occurred so that concerns over contracture development are minimized. Subsequent dressings are fabricated as removable rigid dressings (RRDs) that can be taken off whenever the wound needs to be inspected. Rigid dressings have been predominantly used in the individuals with a traumatic amputation because of lessened concern over wound healing or limb injury from the dressing. While rigid dressings can be used simply as a wound care strategy, they can also be used with a pylon attachment to which components

can be attached, creating a preparatory prosthesis that enables immediate or early weight bearing.

Because little objective data exist that clearly identify a superior wound dressing strategy, the choice of wound management appears to be driven largely by practice conventions, availability of skilled staff, and the personal experience of the surgeon. Greater attention is needed to facilitate rapid wound healing, especially in the individual with a dysvascular amputation in whom the effects of prolonged immobilization may substantively complicate rehabilitation effects. The preprosthetic phase of management, before preparatory prosthetic fitting, can typically last 6 to 10 weeks for the individual with a dysvascular LE amputation, a considerably shorter period of time for the individual with a traumatic LE amputation, and 3 to 6 weeks for the individual with a UE amputation (

12).

Muscle imbalance and postoperative positioning to facilitate comfort leads to the development of knee flexion contracture in the transtibial residual limb and to hip flexion and abduction contractures in the individual with a transfemoral amputation. Contractures are preventable through a postoperative therapy program that emphasizes range of motion exercises and early mobilization. Strengthening of muscle groups that biomechanically substitute for the lost function of the limb is needed. Exercise programs are required to accomplish this task. In the individual with a LE amputation, the hip extensors (gluteus maximus and hamstrings), gluteus medius, hip flexors, and the contralateral ankle plantar flexors all contribute to restoring ambulation ability (

31,

32). In the individual with a UE amputation, proximal shoulder girdle muscle strengthening should be taught, emphasizing the trapezius, serratus anterior, pectoralis major, as well as any residual deltoid and biceps functions.

An individual’s psychological response to amputation may be compared to the grieving process that variably includes identifiable stages of denial, anger, depression, coping, and acceptance. Not every person ultimately adapts to limb loss. The individual’s ultimate response to the psychosocial impact of limb loss is determined by many factors, including the cause of amputation, personal life experience and inner strengths, the available social support system, the care provided by the prosthetic team, and the functional outcome that is achieved through rehabilitation.

Prosthetic Fitting and Training

An understanding of the functional needs of the individual with an amputation, his/her interest and motivation in pursuing prosthetic fitting, and an assessment of his/her ambulatory potential are required to set realistic goals for prosthetic fitting and training. Not all the individuals with an amputation are candidates for prostheses. Although the factors that predict success in prosthetic use are partially understood, a number of factors have been associated with a poor outcome in returning the individual with an amputation to functional ambulation at household or community levels. Negative prognostic factors include a delay in wound healing, the presence of joint contractures, dementia or cognitive disorders, medical comorbidities, and higher levels of limb amputation (transfemoral) (

33,

34,

35). Age has inconsistently been identified as a predictor of prosthetic success, implying that except in advanced age (>80 to 85 years) other factors play a more important role in determining the rehabilitation potential of the individual with an amputation.

As a result of the uncertainty in identifying prosthetic candidates, considerable clinical judgment is required. Some general guidelines can be followed. An individual with an amputation should have reasonable cardiovascular reserve, adequate wound healing, and good soft-tissue coverage, range of motion, muscle strength, motor control, and learning ability to achieve useful prosthetic function. Individuals with an LE amputation who can walk with a walker or crutches without a prosthesis usually possess the necessary balance, strength, and cardiovascular reserve to walk with a prosthesis. Examples of poor candidates for functional prosthetic fitting would be an individual with a dysvascular LE amputation with an open or poorly healed incision, an individual with a transfemoral amputation with a 30-degree flexion contracture at the hip, or an individual with a transradial amputation with a flail elbow and shoulder. Generally, individuals with a bilateral, short, transfemoral amputation over the age of 45 years are considered unlikely candidates for full-length prosthetic fitting. Additional medical problems such as severe coronary artery disease, pulmonary disease, severe polyneuropathy, or multiple-joint arthritis may result in an individual with an amputation who could be fitted with a prosthesis but who may not be a functional prosthetic user. Patients in whom prognosis is poor, life expectancy is short, or with a disease that results in significant fluctuations in body weight are not good candidates. In borderline cases, it may be necessary to proceed with actual prosthetic fitting to determine the eventual prosthetic function. The use of a less costly, RRD with pylon and foot or a preparatory prosthesis is appropriate before a decision is made about fitting such a person with a more costly definitive prosthesis. The overall success rate in restoring functional ambulation in the individual with a lower limb amputation varies approximately from 36% to 70%. Amputation resulting from vascular disease is a manifestation of a severe systemic vasculopathy. The early mortality following major LE amputation is 15% to 20%, largely related to myocardial infarction. Overall, the individuals with dysvascular amputation have a 3- to 5-year 50% mortality, which underlies the importance of successful early rehabilitation to allow for an improved quality of life in their remaining years.

The timing of prosthetic fitting for the individual with an LE amputation remains controversial, reflecting the clinical uncertainty over early versus delayed weight bearing. Because the majority of LE amputations occur as a result of PVD, primary wound healing at the amputation site is of paramount importance. When the rigid dressing was introduced on a wide scale in the 1970s, it was used to implement immediate postoperative prosthesis (IPOP) (a rigid dressing with a pylon and foot) as a means to speed rehabilitation for individuals with LE amputation (

36). Problems with wound healing and

residual limb trauma from poorly fabricated devices and a lack of experienced teams to manage this approach to early postoperative care led to abandoning their use in the individual with a dysvascular amputation. Despite these problems, in selected centers with adequate experience and a process to monitor closely the residual limb, an immediate or early postoperative prosthesis fabricated several weeks after surgery has been used safely in individuals with a dysvascular amputation (

37). Immediate fitting in the younger patient with traumatic amputation has been more successful and is a reasonable method of treatment. Immediate and early postoperative prostheses are, in effect, an RRD with a pylon and foot attached. This device is used to achieve limited partial to full weight bearing, reduce edema, and accomplish initial gait training. Because the fit of these devices is always suboptimal compared to a custom-molded socket, they are not recommended for extended use.

When concern over wound healing dominates clinical care in the postoperative period, prosthetic fitting is delayed until the residual limb has healed adequately to allow unrestricted weight bearing. Providing a prosthesis is typically performed in two stages: a preparatory prosthetic limb phase is followed by the provision of a definitive prosthesis. The preparatory prosthesis is often of simple design, lower performance, and is more accommodating to changes in residual limb volume than is the definitive limb. It allows the individual with an amputation to gain skill and confidence in walking with prosthesis, facilitates residual limb maturation, and affords the rehabilitation team the opportunity to better define the ultimate functional level of the individual. When stump maturation has occurred, a definitive prosthesis is prescribed to meet the anticipated needs of the individual with an amputation.

Stump maturation is an imprecisely defined concept that occurs when the volume of the residual limb has stabilized, soft-tissue atrophy has occurred, and the residual limb has been molded into a cylindrical shape that optimizes prosthetic fitting. This can usually be determined when the individual with an amputation reports a plateau in the number of sock plies worn from day to day and by clinical exam that shows edema resolution. Residual limb maturation, typically, takes about 4 months (

38) but may extend substantially longer depending on the activity level, amount of prosthetic limb use, and coexisting medical disease. After stump maturation occurs, a definitive prosthesis is prescribed to specifically meet the ADLs and vocational and avocational needs of the individual with an amputation. In the case of young children, the prosthesis prescription must also meet any needs related to the development of age-appropriate motor milestones. Although a two-stage approach (preparatory followed by definite limb) is commonly used, financial considerations are becoming increasingly important with many health insurance programs allowing for only a single limb. Under these situations, the prosthetic team may recommend as the initial prosthesis a limb that is projected to meet all the long-term needs of the individual with an amputation. Patients who are not candidates for functional prosthetic use may choose to have a cosmetic prosthesis that has an appearance similar to that of the opposite limb.

Gait Training

After completing the final prosthetic evaluation, the individual with a new amputation will require a period of gait training under the supervision of the physical therapist. The individual with an amputation is instructed on how to put on and take off the prosthesis, how to determine the appropriate number of limb socks to be worn, when and how to check the skin for evidence of irritation, and how to clean and care for the prosthesis. For the individual with a new amputation it is best if the initial gait training occurs while the prosthesis is still capable of being adjusted to permit alignment or length changes that may become apparent during gait training. Gait training often occurs on an outpatient basis and may last from weeks to months. The more proximal levels of amputation require lengthier gait training.

Gait training begins with weight shifting and balance activities while still in the parallel bars. Once weight shifting and balance activities have been mastered, a program of progressive ambulation begins in the parallel bars and progresses to the most independent level of ambulation possible with or without gait aids. Specific training should focus on transfers, knee stability, equal step lengths, and avoiding lateral trunk bending. Following mastery of ambulation on flat, level surfaces, techniques for managing uneven terrain, stairs, ramps, curbs, and falling and getting up off the ground are learned. Moving from a walker to less cumbersome gait aids can be achieved for most individuals with an LE amputation. For higher functioning individuals with an amputation, prosthetic training should include instruction and practice in driving, recreation, and vocational pursuits. Developing the optimal benefit from a prosthesis must take into account the specific mechanical attributes of the components used. For example, using a dynamic response (i.e., energy-storing) prosthetic foot requires loading the prosthetic toe during mid-stance and late stance to capture energy for push off assistance or to activate a prosthetic knee to initiate the swing phase.

Wearing tolerance for the prosthesis must be gradually increased. Initially, the individual with an amputation will wear the prosthesis only for 15 to 20 minutes, removing it to check the condition of the skin. As tolerance to weight bearing increases, the length of wearing time is gradually increased. Several weeks may be required before the individual with an amputation is able to wear the prosthesis full-time. The individual with an amputation may take the prosthesis home when safe and independent ambulation has been demonstrated and residual limb skin checks are assured. Common gait deviations and their causes are highlighted in

Table 74-3.

LE Prosthetic Follow-up

During the initial 6 to 18 months, most individuals with an amputation will experience continued loss of residual limb volume, resulting in a prosthetic socket that will be too large. During this period, return visits should occur frequently enough to ensure that this loss of residual limb volume is being compensated for by the use of additional limb socks or by appropriate modifications of the prosthetic socket. It is usual for an individual with a new amputation to require replacement of the

prosthetic socket during this time because of the significant loss of soft-tissue volume. During follow-up visits, the condition of the residual limb, the prosthesis, the individual’s gait, and the level of function are reviewed (

39). Appropriate medical treatment, prosthetic modifications, or additional therapies are prescribed as needed. When the residual limb volume has stabilized sufficiently and the patient is doing well with the prosthesis, yearly visits to the amputee clinic are appropriate. Once the residual limb has stabilized, the average life expectancy for an LE prosthesis before replacement should be 3 to 5 years.