Chapter 98 Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

John Repicci’s introduction of minimally invasive techniques to unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) has led to renewed interest in UKA. Growth at triple the rate of total knee replacement (TKR) was observed over the past decade,37 driven by the introduction of new technology. In 2004, mobile-bearing UKA was introduced to the United States; in 2006, a haptic guidance system and new adapted devices, as well as personalized UKA with prenavigated single-use instruments, further fueled this growth.

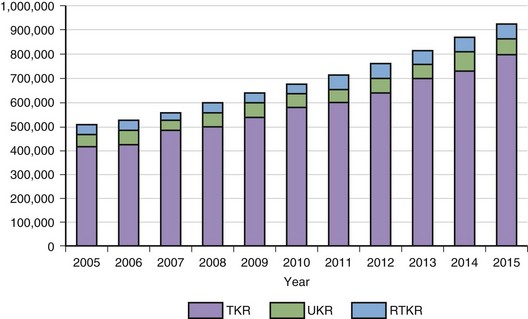

According to Frost and Sullivan (A. Shetty, personal communication, November 2009), the worldwide market for knee replacements in 2008 was $7.3 billion, with a total revenue of $3.21 billion in the United States alone. In 2008, 555,000 primary TKRs were performed in the United States, with projected annual growth rates between 5% and 6% over the next 5 years (Fig. 98-1). Although knee revisions will increase at annual rates of between 3% and 4% from 34,761 in 2008 to 44,500 in 2015, it is estimated that unicompartmental arthroplasty will stay at around 6% to 8% of primary knee replacements, already outnumbering the number of knee revisions. With better results and younger patients, a higher market share of UKA is possible.

Compared with TKR arthroplasty, unicompartmental replacement has the advantage of preserving both cruciate ligaments, yielding a knee with nearly normal kinematics.22,38,49 A study of 42 patients with a bicompartmental or tricompartmental arthroplasty on one side and a unicompartmental replacement on the other showed that more patients preferred the unicompartmental side because it felt more like a normal knee and had better function.8,31 More bone stock may be preserved with UKA. Theoretically, this should make conversion to TKR easier, should it become necessary. This advantage, however, was not initially supported by studies of revision of unicompartmental replacements.3,23,32 Results of revision were not superior to those seen after revision of bicompartmental or tricompartmental replacement, and bone stock deficiency in the femoral condyle or the tibial plateau often had to be augmented with bone graft or special components. These deficiencies are frequently the result of poor surgical techniques or prostheses that unnecessarily invade the bone stock. More modern techniques using surface replacements on the femoral and tibial sides have made the procedure as conservative in practice as it is in theory, and conversions of failed UKA to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) demonstrate results similar to those seen with primary TKR.24

The concept of unicompartmental TKR is an attractive alternative to tibial osteotomy or tricompartmental replacement in the osteoarthritic patient with unicompartmental disease confirmed at arthrotomy.14,22,49 As compared with osteotomy and TKR, unicompartmental arthroplasty has a higher initial success rate and fewer early complications.18,43 Recovery is quicker and occurs with less blood loss, less pain, and better functional results. Survivorship analyses have been reported for tricompartmental replacement, indicating that survivorship with or without cruciate retention can be above 90% after 10 years of follow-up.35,36,40,45 Early studies generated from unicompartmental series show that survivorship is not as good after 10 years, dropping into the 85% range.* However, these series were generated at a time when surgical techniques, implant design, and the quality of polyethylene were not yet perfected. Recent reports demonstrate that patients 60 years and younger have survivor rates above 90% at 10 years for fixed- and mobile-bearing UKA.33,34 A randomized prospective study comparing TKR with unicompartmental knee replacement showed a 15-year survival rate of 89% for UKA and 79% for TKR. Patients undergoing UKA had better range of motion, were more satisfied, and were more active, with a comparable Bristol functioning score. The failure rate at 15 years of UKA was not higher than that seen with TKR.30

Patient Selection

The widespread use of arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee without large mechanical relevant meniscal tears has been questioned21,28 and is not recommended. Osteotomy remains the procedure of choice in the young, very active patient with unicompartmental osteoarthritis. Internal derangement and its treatment in the younger subpopulation are not contraindications to osteotomy but may need to be relieved by an arthroscopic procedure before or after the osteotomy is performed. However, additional studies are needed to clarify the effectiveness of knee arthroscopy in this population. Subluxation and extreme angular deformity are contraindications to both osteotomy and unicompartmental replacement.

Currently, metallic interpositional arthroplasty is not recommended for the treatment of osteoarthritis,1 although this treatment occasionally may be advisable for patients when osteotomy or knee arthroplasty is contraindicated.10,42

Although some authors reported no differences in outcomes regarding age,29,33 others did describe such differences.9,22 Certain fixed-bearing implants such as Miller-Galante and Marmor implants were reported not to have higher failure rates in heavier patients. This was confirmed by Cartier, Argenson, and Pennington.2,7,33 Surovevic even extended the indication for UKA to a BMI of up to 42.47 Berend reported higher failure rates in patients with a BMI above 32 in UKA using an all-polyethylene (PE) tibia.4 Both implants (Repicci II, Biomet, Warsaw, Ind; Eius, Stryker Orthopedics, Mahwah, NJ) were all-PE whether they were an inlay or an onlay, but neither had a tibial keel.

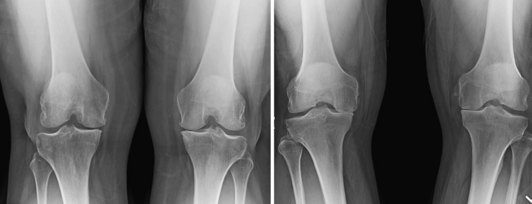

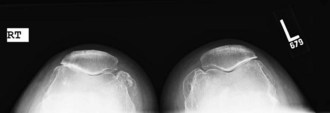

Although most surgeons make their final decision on whether to use a UKA or a TKA at the time of surgery after arthrotomy,22,43,49 special weight-bearing preoperative x-rays are helpful (Fig. 98-2). Standing posteroanterior standing views in extension and flexion (Rosenberg views) are nice screening tools for unicompartmental medial or lateral osteoarthritis (Fig. 98-3). The standing lateral x-ray helps to identify an anteromedial wear pattern and is helpful in predicting whether the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is intact (Fig. 98-4).20 Skyline views may demonstrate patellofemoral (PF) osteoarthritis (Fig. 98-5). PF eburnated bone is considered a contraindication to UKA.

Figure 98-3 Anteroposterior (AP) standing and AP Rosenberg views are helpful in diagnosing lateral osteoarthritis.

Implant Design

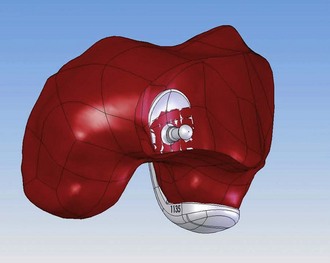

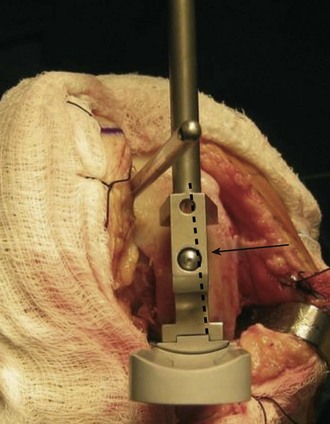

Over the past two decades, many lessons have been learned concerning the ideal design of a unicompartmental arthroplasty. Many early femoral components were narrow in their mediolateral dimension and suffered a high incidence of subsidence of the component into the condylar bone.41,43 The ideal component should be wide enough to maximally cap the resurfaced condyle, widely distributing weight-bearing forces and decreasing the chances of subsidence and loosening. For this reason, multiple sizes should be available to accommodate both small and large patients. Revision studies have shown the inadvisability of deeply invading the condyle with fixation methods.3,23,32 Relatively small fixation lugs appear to be sufficient as long as two lugs or some sort of fin is present to gain rotational fixation. The posterior metallic condyle should fully cap the posterior condyle of the patient to allow physiologic range of motion without impingement and should be divergent to the femoral lugs to optimize cement pressurization against the posterior condyle during insertion. Also, the anterior femoral edge should taper below the subchondral bone, reducing the chance of patellar impingement. Figure 98-6 shows a personalized femoral component, where the anterior edge is tapered below the subchondral bone. It also demonstrates the anatomic restoration of the posterior condyle. Preferably, the femoral component can be supported on top of the distal subchondral bone without resection, but this requires sacrifice of more bone from the tibial side. The coronal articulating topography of the prosthetic components must also consist of a compromise. A flat surface on the femoral component articulating with a flat surface on the tibial component may potentially improve metal-to-plastic contact, but this is difficult to technically line up precisely enough to avoid edge contact throughout the range of motion. An articulating surface with a small radius of curvature articulating on the tibial side with a flat surface creates too much point contact. A femoral surface with a small radius of curvature matched to a similarly small radius on the tibial side can create too much constraint. The ideal surfaces of both components therefore are probably those with a relatively large radius of curvature that allows adequate metal-to-plastic contact without excessive constraint for fixed-bearing UKA.

In the sagittal plane, conformity at first might seem attractive to increase contact area and lower stresses that cause PE wear. Retrievals of worn unicompartmental tibial components have yielded important information regarding wear patterns and their implications for prosthetic design. It appears that the PE wear pattern tends to reproduce the preoperative wear pattern of the osteoarthritic knee.27 As noted by White and associates,50 this tends to be anterior and peripheral on the medial tibial plateau in a varus knee. Moving the femoral component more mesial may change this wear pattern and decrease the edge loading of the very medial aspect of the tibial component. This is even more important in mobile bearing, in that the meniscal bearing is driven through the position of the femoral component. Mesial placement (Fig. 98-7) of the femoral component keeps the meniscal bearing closer to the vertical rail and avoids soft tissue irritation of a subluxing meniscal bearing. If a fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee is too conforming, a higher incidence of component loosening is reported17,44; this applies for fixed-bearing UKA, but not for mobile-bearing UKA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree