Chapter 49 Unani Medicine

Introduction

Introduction

Unani Medicine: Greco-Arabic Healing and the Islamic Genius

The literary sources of Unani medicine (al-tibb al-yunānī, or sometimes referred to simply as “Tibb,” or “Hikmat” in Pakistan and Afghanistan) were Arabic translations of ancient Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Arabic, Persian, Indian, and Chinese medical texts. However, there is no question that the initial, primary, and most honored textual sources were of Greek origin. The Arabs immersed themselves in the medical knowledge and wisdom contained in the writings of Hippocrates (Buqarāt) and Galen (Jālinūs),* as well as Plato (Aflātūn), Aristotle (Aristatīl), Dioscorides, and Empedocles (Abrāqlīdis).

It is well recognized by contemporary historians that the ancient Greek—and to some extent Roman—intellectual heritage of the West would have been almost totally lost were it not for the integrating and synthesizing Arab genius within the Islamic world.1 In this regard, one must marvel at the Arabs’ level of care and precision in “first collecting, then translating, then augmenting, and finally codifying the classical Greco-Roman heritage that Europe had lost.”2 However, “so many people in the West wrongly believe that Islam acted simply as a bridge over which ideas of Antiquity passed to mediaeval Europe. Nothing could be further from the truth, for no idea, theory, or doctrine entered the citadel of Islamic thought unless it became first Muslimized and integrated into the total world-view of Islam.”3

Unani Medicine: Comparisons and Contrasts with Other Health Care Systems

Apart from Unani medicine’s introduction onto the stage of world history as a legitimate synthesis—in time and space—of primarily Greek and Islamic civilizational influences, there is yet another dimension to Unani medicine that is often overlooked and yet of great significance. Along with the great medical traditions of other civilizations of the past, like the Ayurveda of Hindu India or Traditional Chinese Medicine, Unani medicine continues to be preserved and persevere, especially in the face of modern cultural trends in many nations that have moved towards changing the old guards of ancient medicine for the shiny hopes and promises of a new system of powerful drugs, “healing steel,” and high-tech diagnostic tools and machinery. Unani medicine is still practiced today as an organic, living, breathing, whole system of health care helping millions of people around the world (especially in the Indian subcontinent, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Persia [Iran], China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and certain sectors of the Middle East [such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Dubai]).

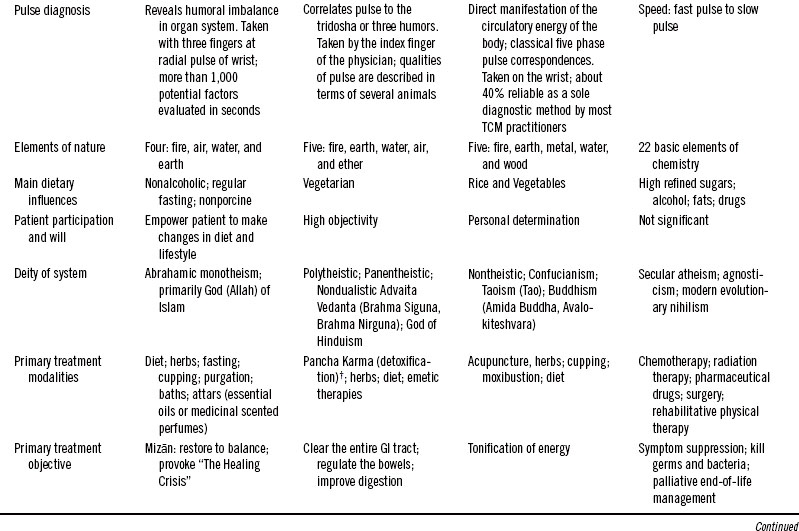

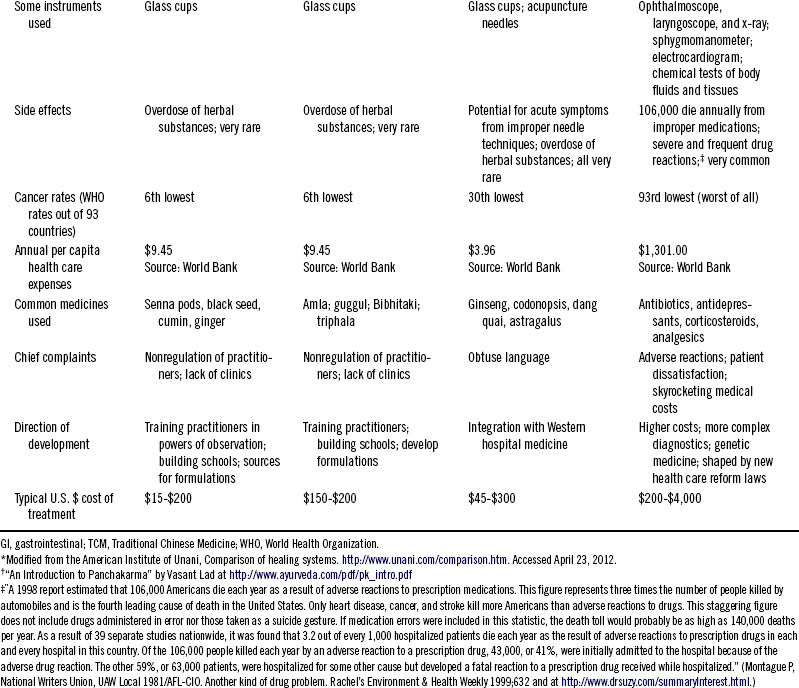

Unani medicine also shares medical theories, philosophies, cultural identity, and spiritual insights regarding human health and disease with ancient systems of medicine, such as Hindu India’s Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine, because its knowledge and wisdom hail from the traditional Eastern “Orient,” while contrasting tremendously with the single system of contemporary medicine that one could say belongs to the world of the modern Western “Occident.”* This is what led Hakim Chishti (an American researcher and practitioner of the science and art of Unani medicine) to present a very thoughtfully indexed comparison between all of these healing systems (as found on http:/www.unani.com whose general points are in Table 49-1).

History

History

Contributions and Influences from Antiquity

There were a variety of strands of medicine that came together at the crossroads of Islamic history that proved to be of tremendous significance for the birth of Islamic medicine and for Unani medicine in particular.4

In summary, the “scientific knowledge that originated in India, China, and the Hellenistic world was sought out by Arab and Muslim scholars and then translated, refined, synthesized, and augmented at different centers of learning, starting at Jundishapur in Persia around the sixth century—even before the coming of Islam—and then moving to Baghdad,* Cairo, and finally Toledo and Cordoba, from whence this knowledge spread to Western Europe.”2

The Torchbearers of Islamic Medicine

Ibn Ishāq (Johannitus Onan), 809-873 AD

Hunayn ibn Ishāq al- Ibādi was “the greatest of all translators of this period … [and] an outstanding physician of his day. [He] often translated texts from Greek into Syriac. At other times he would translate directly from Greek into Arabic.”4 He was “reputed to have been paid for his manuscripts by an equal weight of gold. He and his team of translators rendered the entire body of Greek medical texts, including all the works of Galen, Oribasius, Paul of Aegin, Hippocrates, and the Materia Medica of Dioscorides, into Arabic by the end of the ninth century. These translations established the foundations of a uniquely Arab medicine.”2

Ibādi was “the greatest of all translators of this period … [and] an outstanding physician of his day. [He] often translated texts from Greek into Syriac. At other times he would translate directly from Greek into Arabic.”4 He was “reputed to have been paid for his manuscripts by an equal weight of gold. He and his team of translators rendered the entire body of Greek medical texts, including all the works of Galen, Oribasius, Paul of Aegin, Hippocrates, and the Materia Medica of Dioscorides, into Arabic by the end of the ninth century. These translations established the foundations of a uniquely Arab medicine.”2

Al-Tabari, 810-855 AD

Ali ibn Rabbān al-Tabari was the teacher of the great Rhazes. He was the “author of the first major work of Islamic medicine … entitled Kitāb Firdaws al-Hikma (‘The Book of the Paradise of Wisdom’). In 360 chapters, he summarized the various branches of medicine, devoting the last discourse, which consisted of 36 chapters alone, to a study of Indian medicine (Ayurveda). The work, the first large compendium of its kind in Islam, is of particular value in the fields of pathology, pharmacology, and diet, and clearly displays the synthetic nature of this new school of medicine, now coming into being.”4

Al-Rāzi (Rhazes), 841-926 AD

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Rāzi was born in the town of Rayy in Persia, near what is present day Tehran. He was reputed to be Islamic medicine’s greatest clinician. His works include al-Kitāb al-Mansūri (The Book of Mansūr or the Latin Liber Almansoris, in which Rhazes delineated principles of medical theory, diet, pharmacology, dermatology, oral hygiene, epidemiology, toxicology, and even climatology and its effects on the human body), al-Judari wa al-Hasbah (Smallpox and Measles, which was the first treatise ever written on the subject), and his magnum opus al-Kitāb al-Hāwī (The Comprehensive Work or the Liber Continens of later Latin translators; this monumental collection of 25 volumes contained all the medical knowledge of the age, including the master’s own observation and experience).2

Ibn Sīna (Avicenna), 980-1037 AD

Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn ‘abd Allāh ibn Sīna was born in the city of Bukhāra in what is today Uzbekistan. He was the preeminent physician of his time, earning the epithet of “Prince of Physicians.” He began studying medicine at the precocious age of 13, became a physician at 16 years of age, attended to kings and princes at 18 years of age, and was appointed as court physician to the ruler of a Persian province at 20 years of age. His literary corpus includes Kitāb as-Shifā’ (The Book of Healing, which was primarily a text of encyclopedic proportions on medicine and philosophy) and al-Qanūn fi ’l-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine, a one-million-word text summarizing the entire Hippocratic and Galenic traditions and describing the Syro-Arab and Indo-Persian medical practices of his time). The Canon quickly was, for several hundreds of years, the standard medical textbook of the Islamic, medieval Christian, and later Indo-Pakistani worlds. Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine was “a five-volume compendium of Greek and Islamic healing that became one of the principal textbooks in European universities centuries later.”6

It is from this remarkable polymath that Unani medicine draws its breath of life. Avicenna is perceived by some to be the “Father of Unani Medicine,” and his Canon its gospel.2

Post-Avicennan Medicine

Egypt and Syria: Ibn Nafīs

Ibn Nafīs was born in Damascus and died in Cairo in the twelfth century AD. Ibn Nafīs has only recently gained fame as the rightful discoverer of pulmonary circulation, which was mistakenly thought to have been identified in the 16th century by Michael Servetus. There have been several studies in recent years that incontestably demonstrated that Ibn Nafīs discovered the lesser circulation of the blood before Servetus. See A.O. Soubani’s “The Discovery of the Pulmonary Circulation Revisited,” in which this medical doctor and researcher pooled together and summarized a host of earlier literature regarding this hallmark of medical subjects.4,7

Spain and Morocco: Al-Zahrāwī (Albucasis) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes)

Abu al-Qāsim al-Zahrāwī (976-1013 AD) is considered to be the greatest surgical figure in Islamic medicine. He was also original in this medical arena in inventing and manufacturing the requisite surgical instrumentation that did not exist, or existed previously in very crude form only, to conduct operations as painlessly and effectively as possible. Some of these instruments of surgery have not changed significantly in design for over 1,000 years. A more comprehensive sketch of the significance of Albucasis in the field of surgery can be found in Kasule.8

Abu al-Walīd Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Rushd9 (1126-1198 AD) was born in Cordoba, where he trained in law and philosophy, although he made his living as a physician. He wrote his Kitāb al-Kulliyyāt (the Latin translator’s Colliget, The Book of General Principles) in which he covered the whole field of medicine in abridged form.

Metaphysical and Philosophical Foundations

Metaphysical and Philosophical Foundations

Epistemology and Ontology

Within the Islamic, as well other traditional religious worlds, knowledge has a definite hierarchical structure.* This hierarchy maintains the essential links that exist between Heaven and Earth, between God and humans. First, there exists an acknowledgement of a presiding Divine Knowledge (i.e., God as Wise and All-Knowing). Following this is the knowledge found in Revelation (i.e., a perfect dispensation from Heaven that enlightens the human intellect).† As this revelatory knowledge sparks the heart’s depths, it necessarily begins to involve the mind–intellect in its quest for knowledge of this earthly domain (‘ilm al-dunya), this physical world.

Cosmology and the Human Microcosm

The basic cosmologic premise in Islam, as well as in other traditions such as Hinduism, Christianity, and Judaism, is that the Absolute Truth of Divinity (al-Haqq) manifests Itself in the world of forms and within the human heart in a process called the “arc of descent.”‡ There is in response to this arc of descent of the Divine a reciprocal “arc of ascent” of the human spirit.10 These adwār (“arcs” or “cycles”) of descent and ascent relate directly to the interdependence of all things on all levels of existence. Everything in creation is perceived as acknowledging, in one form or another, the all-pervading Divine Presence. From the traditional view, the human being is seen as the most concentrated theophany (i.e., a locus of Divine Presence in the world of forms), especially as it concerns the qualities of an active intellect and free will. According to the Hermetic dictum, “As Above, so too below,” the human being acts as a mirror to the Divine. Furthermore, the Sufis (the mystics of Islam) have a popular saying that addresses this reality on the cosmic scale: al-insān qawn saghīr wa ’l-qawn insān kabīr (“Man is a small universe and the universe is a large man”).

The guiding principle of the dynamic interplay between the Divine Order and the rest of creation is called Tawhīd (“the principle of Divine Unity”). All traditional sciences agree that there exists a dependence of creation on the Divine, an interdependence between all forms in the cosmos, and an intradependence of all elements within each specific form. There is an obvious analogy to the profound knowledge found in that sacred oriental symbol of the Tao’s Tai Chi (“Supreme Principle of Unity”) with the complimenting and harmonizing forces of Yin and Yang. This is also known in Islamic cosmologic language as al-wahdah fi ’l-kathrah wa ’l-kathrah fi ’l-wahdah (“the one in the many and the many in the one”).

Unani medicine bases its medical theories of diagnosis and treatment upon this specific understanding of the intradependent relationships that exist between the four humors as it concerns the subtle (latīf) aspects of human physiology and spiritual psychology.*

Unani Medical Theory in Principle

Unani Medical Theory in Principle

The Doctrine of the Seven Naturals

There are hosts of medical systems around the world with their own understanding of what constitutes the primary and basic functional components that cause health to reign or disease to take root, progress, and finally show itself in constellations of signs and symptoms of illness. In Chinese medicine, we have physiologic concepts such as Qi, Blood, Yin, and Yang. In conventional medicine, physiology is dominated with the key concepts of organic issues relating to organ tissue morphology (anatomy) and fluid dynamics (medical biochemistry).

Elements, Qualities, Properties, and States

Fire (nār), which is hot and dry (hār and yābis): determines energy state.

Air (hawā’), which is hot and wet (hār and ratab): determines the gaseous state.

Water (mā’), which is cold and wet (bārid and ratab): determines the liquid state.

Earth (ardh), which is cold and dry (bārid and yābis): determines the solid state.

These elements do not mean literally clods of dirt, buckets of water, and so forth. “Likewise, the burning fire that we see is not the element fire, which is really the potentiality of fire within the substance.”11

Temperaments

The interplay between the qualities of the elements leads ultimately to a uniform configuration of a temperament. “Each [Temperament] is named after a certain Humor, and is characterized by the predominance of that Humor and its associated basic qualities.”12 The classical temperaments correlate well to today’s psychological constitutional types: choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, and sanguine. Imbalances of temperaments cause disharmony, especially on the mental and emotional fronts. The following is a concise, but thorough medical depiction of the temperaments (Table 49-2).

TABLE 49-2 The Four Different Temperaments

| Sanguine Temperament | |

|---|---|

| Humor | Blood |

| Basic qualities | Hot and wet |

| Face | Oval or acorn-shaped face and head. Delicate, well-formed mouth and lips. Beautiful almond-shaped eyes, often brown. An elegant, swanlike neck. |

| Physique | In youth, balanced, neither too fat nor too thin. Moderate frame and build. Elegant, statuesque form, with ample, luxuriant flesh. Joints well-formed; bones, tendons, veins not prominent. Can put on weight past 40 years, mostly around hips, thighs, buttocks. |

| Hair | Thick, luxuriant, wavy. Abundant facial and body hair in men. |

| Skin | Pink, rosy, blushing complexion. Soft, creamy smooth, luxurious feel. Pleasantly warm to the touch. |

| Appetite | Quite hearty, often greater than digestive capacity. A predilection for rich gourmet foods. |

| Digestion | Good to moderate; balanced. Can be overwhelmed by excessive food. |

| Metabolism | Moderate, balanced. Bowel tone can be a bit lax. |

| Predispositions | Metabolic excesses of the blood. Uremia, gout, diabetes, high cholesterol. Intestinal sluggishness, putrefaction. Congested, sluggish liver and pancreas. Congested blood, bleeding disorders. Respiratory catarrh, congestion, asthma. Urinary conditions, genitourinary disorders. Excessive menstruation in women. Skin conditions, hypersensitivity, capillary congestion. |

| Urine | Tends to be rich or bright yellow and thick. |

| Stool | Well-formed, neither too hard nor too soft. |

| Sweat | Balanced, moderate. |

| Sleep | Moderate, balanced, sound. Can be some snoring. |

| Dreams | Usually pleasant, of a charming, amusing, romantic nature. Travel, enjoyment, games, distractions. |

| Mind | Faculty of judgment well-developed. A synthetic intellect that likes to see the whole picture. An optimistic, positive mental outlook. Rather conventional and conformist; good social skills. |

| Personality | Exuberant, enthusiastic, outgoing. Optimistic, confident, poised, graceful. Expansive, generous. Romantically inclined; loves beauty, aesthetics, arts. Sensual, indulgent nature. Sociable, gregarious, light-hearted, cheerful. |

| Choleric Temperament | |

|---|---|

| Humor | Yellow bile |

| Basic qualities | Hot and dry |

| Face | Broad jaw. Sharp nose, high cheekbones. Sharp, angular facial features. Reddish face common. Sharp, fiery, brilliant, penetrating eyes and head. |

| Physique | Compact, lean, wiry. Good muscle tone and definition. Prominent veins and tendons. Broad chest common. An active, sportive type. Weight gain usually in chest, arms, belly, upper body. |

| Hair | Often curly. Can also be thin, fine. Balding common in men. Blonde or reddish hair common. |

| Skin | Ruddy or reddish color if heat predominates; sallow or bright yellow if bile predominates. Rough and dry, quite warm. |

| Appetite | Sharp and quick. Soon overcome by ravenous hunger. Fond of meat, fried foods, salty or spicy foods, alcohol, intense or stimulating taste sensations. |

| Digestion | Sharp and quick. Tendency towards gastritis, hyperacidity, acid reflux. When balanced and healthy, can have a “cast iron stomach,” able to digest anything. |

| Metabolism | Strong, fast, active; catabolic dominant. Strong innate heat of metabolism. Liver and bile metabolism can be problematic. Digestive secretions strong, bowel transit time short. Adrenals, sympathetic nervous system dominant. Strong inflammatory reactions. |

| Predispositions | Fevers, infections, inflammation. Hives, rashes, urticaria. Fatty liver, bilious conditions. Hyperacidity, acid reflux, inflammatory and ulcerative conditions of middle GI tract. Headaches, migraines, irritability. Eyestrain, red sore eyes. Purulent conditions. High cholesterol, cardiovascular disorders. Gingivitis. Bleeding disorders from excess heat, choler in the blood. Hypertension, stress. |

| Urine | Tends to be scanty, dark, thin. Can be hot or burning. |

| Stool | Tends towards diarrhea, loose stools. Can have a yellowish color, foul odor. |

| Sweat | Profuse, especially in summer, or with vigorous physical activity. Strong body odor. Sensitive to hot weather, suffers greatly in summer. |

| Sleep | Often fitful, restless, disturbed, especially with stress, indigestion. Often tends to wake up early or in the middle of the night. |

| Dreams | Often of a military or violent nature. Dreams of fire, red things common. Fight or flight, confrontation. |

| Mind | Bold, daring, original, imaginative, visionary. Ideation faculty well-developed. Brilliant intellect, sharp penetrating insight. The idea man who prefers to leave the details to others. |

| Personality | Prone to anger, impatience, irritability; short temper. Bold, courageous, audacious, confrontational, contentious. Dramatic, bombastic manner; high powered personality. The rugged individualist and pioneer; thrives on challenge. The fearless leader. Seeks exhilaration, intense experiences. Driven, “Type A” personality. Prone to extremism, fanaticism. |

| Melancholic Temperament | |

|---|---|

| Humor | Black bile |

| Basic qualities | Cold and dry |

| Face | Square or rectangular head and face. Prominent cheekbones, sunken hollow cheeks common. Small, beady eyes. Teeth can be prominent, crooked or loose. Thin lips. |

| Physique | Tends to be thin, lean. Knobby, prominent bones and joints common. Prominent veins, sinews, tendons. Muscle tone good, but tends to be stiff, tight. Rib cage long and narrow, with ribs often prominent. Can gain weight in later years, mainly around midriff. |

| Hair | Color dark, brunette. Thick and straight. Facial and body hair in men tends to be sparse. |

| Skin | A dull yellow or darkish, swarthy complexion. Feels coarse, dry, leathery, cool. Calluses common. |

| Appetite | Variable to poor. Varies, fluctuates according to mental or emotional state. |

| Digestion | Variable to poor; irregular. Digestion also varies according to mental or emotional state. Colic, gas, distension, bloating common. |

| Metabolism | Often slow. Can also be variable, erratic. Prone to dehydration. Nervous system consumes many nutrients, minerals. GI function variable, erratic; digestive secretions tend to be deficient. Blood tends to be thick. Nutritional deficiencies can cause a craving for sweets, starches. Thyroid tends to be challenged, stressed. |

| Predispositions | Anorexia, poor appetite. Nervous, colicky digestive disorders. Constipation. Spleen disorders. Nutritional and mineral deficiencies, anemia. Blood sugar problems, hypoglycemia. Wasting, emaciation, dehydration. Poor circulation and immunity. Arthritis, rheumatism, neuromuscular disorders. Nervous and spasmodic afflictions. Dizziness, vertigo, ringing in ears. Nervousness, depression, anxiety, mood swings. |

| Urine | Tends to be clear and thin. |

| Stool | Can either be hard, dry, compact; or irregular, porous, club-shaped. Constipation, irritable bowel common. |

| Sweat | Generally scanty. Can be subtle, thin, furtive, indicating poor immunity. Nervous stress can increase sweating. |

| Sleep | Difficulty falling asleep, insomnia. Stress, overwork, staying up late aggravates insomnia. Generally a light sleeper. |

| Dreams | Generally dark, moody, somber, disturbing. Themes of grief or loss common. |

| Mind | An analytical intellect; detail oriented. Efficient, realistic, pragmatic. Reflective, studious, philosophical. Retentive faculty of memory well-developed. Thinking can be too rigid, dogmatic. A prudent, cautious, pessimistic mental outlook. |

| Personality | Practical, pragmatic, realistic. Efficient, reliable, dependable. A reflective, stoic, philosophical bent. Can be nervous, high strung. Frugal, austere; can be too attached to material possessions. Serious, averse to gambling and risk taking. Can be moody, depressed, withdrawn. Can easily get stuck in a rut. Excessive attachment to status quo. |

| Phlegmatic Temperament | |

|---|---|

| Humor | Phlegm |

| Basic qualities | Cold and wet |

| Face | Round face; full cheeks, often dimpled. Soft, rounded features. Double chin, pug nose common. Large, moist eyes. Thick eyelids and eyelashes. |

| Physique | Heavy frame, stout, with flesh ample and well-developed. Often pudgy, plump, or overweight; obesity common. Joints dimpled, not prominent. Veins not prominent, but can be bluish and visible. Lax muscle tone common. Feet and ankles often puffy, swollen. Women tend to have large breasts. Weight gain especially in lower body. |

| Hair | Light colored, blondish hair common. Light facial and body hair in men. |

| Skin | Pale, pallid complexion; very fair. Soft, delicate, cool moist skin. Cool, clammy perspiration common, especially in hands and feet. |

| Appetite | Slow but steady. Craves sweets, dairy products, starchy glutinous foods. |

| Digestion | Slow but steady to sluggish. Gastric or digestive atony common. Sleepiness, drowsiness after meals common. |

| Metabolism | Cold, wet, and slow. Conserves energy, favors anabolic metabolism. Congestion, poor circulation, especially in veins and lymphatics. Kidneys slow, hypofunctioning, inefficient. Adrenals and thyroid tend towards hypofunction; basal metabolism low. Metabolic water drowning out metabolic fire. |

| Predispositions | Phlegm congestion. Water retention, edema. Lymphatic congestion, obstruction. Poor venous circulation. Gastric atony, slow digestion. Hypothyroid, myxedema. Adrenal hypofunction. Weight gain, obesity. Frequent colds and flu. Chronic respiratory conditions, congestion. Swollen legs, ankles, feet. Cellulite. Poor tone of skin, muscles, and fascia. |

| Urine | Tends to be clear or pale and thick. Tends to be scanty in volume, with excess fluid accumulation in the body. |

| Stool | Well-formed, but tends to be slightly loose, soft. Bowels tend to be sluggish. |

| Sweat | Cool, clammy sweat common, especially on hands and feet. Sweating can be easy and profuse, especially with kidney hypofunction. Sensitive to cold weather; suffers greatly in winter. |

| Sleep | Very deep and sound. Tends towards excessive sleep, somnolence. Snoring common; can be loud or excessive. |

| Dreams | Generally very languid, placid. Water and aquatic themes common. |

| Mind | Tends to be dull, foggy, slow. Slow to learn, but once learned, excellent and long retention. Patient, devoted, faithful. Faculty of empathy well-developed. Sentimental, subjective thinking. A calm, good-natured, benevolent mental outlook. |

| Personality | Good natured, benevolent, kind. Nurturing, compassionate, sympathetic, charitable. Great faith, patience, devotion; tends to be religious, spiritual. Sensitive, sentimental, emotional, empathetic. Passive, slow, sluggish; averse to exertion or exercise. Calm, relaxed, takes life easy. Excessive sluggishness can lead to depression. |

GI, gastrointestinal.

From Osborn D. The four temperaments. http://www.greekmedicine.net/. Accessed April 23, 2012. Used with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ayn al-Mulk al-Shirāzī was responsible, at least in large part, in composing The Medicine of Dara Shukūh, which is the last great medical encyclopedia written in the world of Islam.

Ayn al-Mulk al-Shirāzī was responsible, at least in large part, in composing The Medicine of Dara Shukūh, which is the last great medical encyclopedia written in the world of Islam. Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the spiritual pole of Shiite Islam, says: Yā man Ismuka dawā’, wa dhikruka shifā’ (“Oh Ye whose Name is a sacred medicine, and in whom remembrance of Thee [dhikruka] is a healing balm …”).

Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the spiritual pole of Shiite Islam, says: Yā man Ismuka dawā’, wa dhikruka shifā’ (“Oh Ye whose Name is a sacred medicine, and in whom remembrance of Thee [dhikruka] is a healing balm …”). iyyah (“principles of natural physiology”), comprised of the “Seven Naturals” that are the pillars and determinants of health. These are as follows:

iyyah (“principles of natural physiology”), comprised of the “Seven Naturals” that are the pillars and determinants of health. These are as follows: dā’)

dā’) āl)

āl)