13 Trunk and spine

Pain in the back is the commonest symptom encountered in orthopaedic practice. Indeed, if accident cases are excluded, it probably accounts for nearly a third of all orthopaedic out-patient attendances.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF BACK AND SCIATIC SYMPTOMS

Exposure

The patient should be stripped completely, except for undergarments and, in women, a brassière.

Steps in routine examination

A suggested plan for the routine clinical examination of the back is summarised in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the back

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE BACK, WITH NEUROLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE LOWER LIMBS | |

| (Patient standing) | Costo-vertebral joints |

| Inspection | Range indicated by chest expansion |

| Bone contours and alignment: | Sacro-iliac joints |

| (?visible deformity) | (Impracticable to assess range) |

| Soft-tissue contours | ? Pain on movement imparted by |

| Colour and texture of skin | lateral compression of pelvis |

| Scars or sinuses | (Patient recumbent) |

| Palpation | Palpation of iliac fossae |

| Skin temperature | Examine specifically for abscess |

| Bone contours | or mass |

| Soft-tissue contours | Neurological state of lower limbs |

| Local tenderness | Straight leg raising test |

| Movements | Muscular system |

| Spinal joints | Sensory system |

| Flexion | Reflexes |

| Extension | |

| Lateral flexion | |

| Rotation | |

| ? Pain on movement | |

| ? Muscle spasm | |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF BACK PAIN AND SCIATICA | |

| This is important if a satisfactory explanation for the symptoms is not found on local examination. The investigation should include: | |

| 1. the abdomen | |

| 2. the pelvis, including rectal examination | |

| 3. the lower limbs | |

| 4. the peripheral vascular system | |

| 3. GENERAL EXAMINATION | |

| General survey of other parts of the body. The local symptoms may be only one manifestation of a widespread disease | |

Movements of the spinal column and related joints

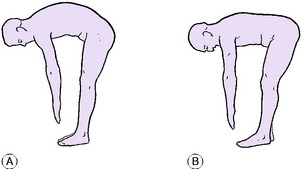

The spinal column. The joints of the spinal column must necessarily be considered as a group, for it is impracticable to study the movement of each joint independently. The movements to be examined are flexion, extension, lateral flexion to right and left, and rotation to right and left. It should be noted particularly whether the spinal muscles go into protective spasm when movement is attempted. Flexion: Instruct the patient to stretch the fingers towards the toes, keeping the knees straight. It is important to judge what proportion of the movement occurs at the spine and how much is contributed by hip flexion (Fig. 13.1). Some patients can almost reach their toes, despite a stiff back, simply by flexing unusually far at the hips. (Normally the hamstrings limit hip flexion to about 90 ° when the knees are straight.) The range may be expressed roughly as a percentage of the normal, or as the distance by which the fingers fail to reach the floor. A more accurate assessment is made by measuring the linear widening of the interspinous spaces as indicated by a tape measure laid along the line of the spinous processes, which may be marked with a pen. The excursion of the spinous processes between full extension and fullest flexion may thus be measured on the tape. An excursion of four centimetres between the twelfth thoracic spinous process and the first sacral prominence between full extension and fullest flexion indicates good lumbar mobility. Extension: Instruct the patient to arch the spine backwards, looking up at the ceiling. Judge the range and express approximately as a percentage of the normal; or measure the excursion as described above. Lateral flexion: Instruct the patient to slide each hand in turn down the lateral side of the corresponding thigh. Observe the range. Rotation: With the feet fixed, the patient rotates the shoulders towards each side in turn. Hold the pelvis steady, and note the range of spinal rotation as distinct from that which occurs at the knees and hips.

Related joints. The costo-vertebral joints: The mobility of the costo-vertebral joints is judged from the range of chest expansion. The normal difference in chest girth between full inspiration and full expiration is about 7 or 8 cm. A marked reduction of chest expansion is of particular significance when ankylosing spondylitis is suspected. The sacro-iliac joints: It is not practicable to measure the range of sacro-iliac movement. But the joints should be moved passively to determine whether pain is produced, as it will be in arthritic conditions of the joints. A simple method is to grip each iliac crest and compress the pelvis strongly from side to side.

Palpation of iliac fossae and groins

Palpation of the iliac fossae and groins is an essential step in the examination of the back. Its specific purpose is to determine whether or not there is a soft-tissue thickening or abscess. It should be remembered that a ‘psoas’ abscess originating from a tuberculous lesion of the lumbar spine first becomes palpable deep in the iliac fossa. Such an abscess is felt most easily by pressing the flat palmar surface of the hand and fingers against the flat inner aspect of the iliac bone. To do this the surgeon must stand at the side of the couch corresponding to the side being examined – that is, he must stand on the right of the patient to examine the right iliac fossa and on the left to examine the left iliac fossa (Fig. 13.2).

Neurological examination of the lower limbs

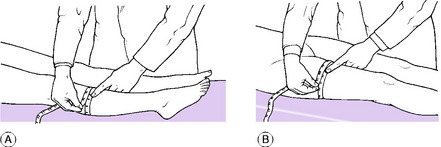

Straight leg raising test. Holding the knee straight, lift each lower limb in turn to determine the range of pain-free movement (normal = 90 °; often more in women) (Fig. 13.3). When associated with clearly defined sciatica (and in the absence of gross disease of the hip), marked impairment of straight leg raising by pain suggests mechanical interference with one or more of the roots of the sciatic nerve. The pain is easily explained. Even a normal sciatic nerve is tautened by straight leg raising, though not to the point of causing pain by dragging on the meningeal sheath that encloses the nerve root. If a nerve is already stretched or anchored, as by a protruded piece of an intervertebral disc or a tumour, the further tautening entailed in lifting the limb is sufficient to cause pain.

Fig. 13.3 The straight leg raising test, an important part of the neurological examination of the lower limbs.

When a nerve is tensely stretched, raising the straight leg on the unaffected side may cause pain on the affected side. This sign, termed the crossed sciatic reflex, is a well-recognised feature of prolapsed lumbar intervertebral disc with nerve pressure.

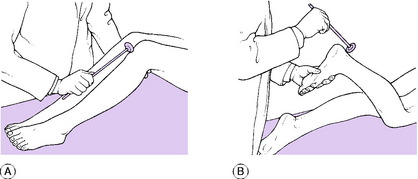

Muscular system. Examine the muscles for wasting, hypertrophy, and fasciculation. Note the tone and test the power of each muscle group, comparing it with its counterpart in the opposite limb. Circumferential measurement is a reliable method of comparing the bulk of the calf muscles, the girth being measured at the widest part or ‘equator’ (Fig. 13.4A). Circumferential measurement of the thighs, on the other hand, tends to be inaccurate, and may be misleading, on account of the conical shape of the thigh (Fig. 13.4B). Often a more accurate assessment of the relative volume of the two thighs is obtained from inspection and palpation. If the thighs are measured, the girth should be taken on each side at an equal distance above the knee – 12 or 15 cm above the upper margin of the patella is usually a convenient level.

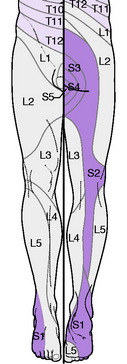

Sensory system. Examine the patient’s sensibility to touch and pin prick, paying particular attention to the sites of any impairment. A knowledge of the innervation of the dermatomes (Fig. 13.5) is essential as this may give an indication of the level of any nerve roots affected. When indicated, test also the sensibility to deep stimuli, joint position, vibration, and heat and cold.

Reflexes. Compare on the two sides the knee jerk (dependent mainly on the L4 nerve) and the ankle jerk (mainly S1). It is important to note not only the presence or absence of the response, but also any difference of intensity (Fig. 13.6). Test the plantar reflex.

Imaging

Radiographic examination. If the complaint is clearly localised to the thoracic spine, antero-posterior and lateral radiographs of that area alone will usually suffice. If the lumbar spine is the part complained of, radiographs should include not only antero-posterior and lateral views of the lumbar spine but also at least one view of the sacro-iliac joints, pelvis, and hip joints. In cases of doubt additional projections may be required. Oblique projections – from half right and half left – are essential for the proper study of the sacro-iliac joints and the posterior intervertebral (facet) joints of the lumbar region. If a spinal tumour is suspected further imaging with magnetic resonance scanning is required.

Other methods of imaging. Radioisotope bone scanning p. 21 is of particular value in examination of the spinal column, especially in the early detection of metastatic deposits.

Computerised tomography (CT scanning) p. 12 is valuable in selected cases. It gives cross-sectional images of the trunk that reveal bony abnormalities very clearly.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES AND DEFORMITIES

LUMBAR AND SACRAL VARIATIONS

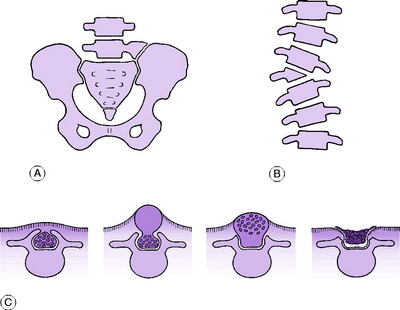

Minor variations of the bony anatomy are common, especially in the lumbar and sacral regions. Most are of little practical importance. They include: deficient or rudimentary lowest ribs; incomplete or complete incorporation of the fifth lumbar vertebral body in the sacrum (sacralisation of the fifth lumbar vertebra); persistence of the first sacral segment as a separate vertebra (lumbarisation of the first sacral vertebra); and over-development of the fifth lumbar transverse process on one or both sides with, in marked cases, a false joint between the hypertrophied process and the ilium (Fig. 13.7A). In the last- mentioned condition the false joint is sometimes a source of pain.

HEMIVERTEBRA

In this anomaly a vertebra is formed in one lateral half only. The defect may occur at any level. The body of the half-vertebra is wedge-shaped, and the spine is angled laterally at the site of the defect (Fig. 13.7B). This anomaly is a rare cause of scoliosis.

SPINA BIFIDA (Spinal dysraphism)

The basic fault in spina bifida is a failure of the embryonic neural plate to fold over to form a closed neural tube, or of mesodermal tissue fully to invest the neural tube as it does in the normal embryo to form the vertebral arch with its spinous process and the surrounding muscles and ligaments. Different grades of the anomaly are shown in Figure 13.7C.

In most cases spina bifida is of minor degree and not a cause of disability. Indeed it is often found incidentally during radiography for some other reason. The importance of spina bifida lies in the fact that in the more severe forms there is a co-existing lesion of the nerve elements. The subject of spina bifida with neurological involvement was discussed in Chapter 11 p. 171.

SCOLIOSIS

Idiopathic structural scoliosis

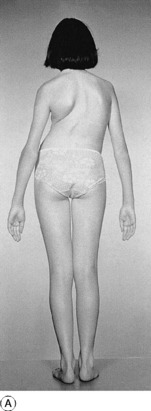

Pathology. Any part of the thoraco-lumbar spine may be affected. There is a primary structural curve, with secondary compensatory curves above and below. The pattern of curve and its natural evolution are fairly constant for each site, and the following types are recognised: lumbar scoliosis, thoraco-lumbar scoliosis, and thoracic scoliosis (Fig. 13.8A). The lateral curvature is constantly accompanied by rotation of the vertebrae on a vertical axis, the body of the vertebra rotating towards the convexity of the curve and the spinous process away from the convexity. By thrusting the ribs backwards on the convex side this rotation increases the ugliness of the deformity (Fig. 13.8).

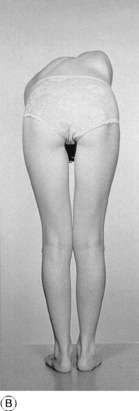

Treatment. The first essential is to assess the prognosis for progression of the deformity from a consideration of the age of onset and the site and severity of the curve. This requires the identification of the first and last vertebrae in the primary curve and the measurement of the Cobb angle between them on an erect AP radiograph of the spine (Fig. 13.9). When the prognosis is good (for instance, in most cases of lumbar scoliosis) expectant treatment, with regular clinical and radiological reviews every six months, may be all that is required. But when the prognosis is poor (as in thoracic scoliosis with early onset or a curve in excess of 45–50°) active treatment is advised. This usually necessitates operation, and much surgical endeavour has been spent in the quest for an effective and safe method of correcting the deformity and maintaining the correction while fusion occurs. Surgical treatment is usually deferred until early adolescence to minimise the loss of height which may result from fusion of a significant length of the growing spine. To prevent further deterioration in the curvature during this waiting period, conservative management with various types of orthotic bracing has been used.

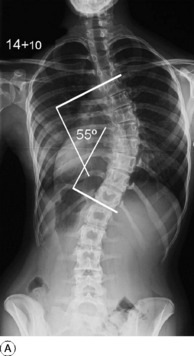

For many years the brace most commonly employed was the Milwaukee brace. This used the principle of three-point correction by distracting the spine between a pelvic band and an occipito-cervical support, with additional lateral pressure from a pad applied to the chest wall at the apex of the curvature. Recently doubt has been cast on the effectiveness of this type of bracing, and because of frequent problems of acceptance by the patient, an alternative under-arm thoraco-lumbar jacket, or Boston brace (Fig. 13.10), has been used. This provides only two-point correction and it acts by flattening the lumbar lordosis; thus it is most suitable for lower curvatures with an apex below the ninth thoracic vertebra.

The principle of surgical treatment is to fuse the joints of all the vertebrae within the primary curve, after having first achieved the greatest possible correction of the curvature. When surgical treatment was first introduced correction was obtained by pre-operative traction or corrective plaster casts. It is now routinely gained at the time of operation by the use of an internal corrective implant. For many years the device used for this purpose was the Harrington distraction rod. This was inserted posteriorly in the concavity of the curve between two hooks placed under the laminae of the top and bottom vertebrae and then forcibly elongated to produce straightening. The results from this technique were encouraging, with up to 50% correction of the lateral curvature, though this was not reflected in improvement of the cosmetic deformity, which largely results from vertebral rotation. This led to a search for other methods of correction including the use of anterior interbody fixation devices, though these necessitated thoracotomy with its associated morbidity in terms of decreased lung function. Currently most specialist surgeons favour posterior correction with multiple-level segmental pedicle screw fixation devices (Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation) (Fig. 13.11). This was an advance over the Harrington instrumentation because it improved correction in both the sagittal and coronal planes.

Fig. 13.11 A and B Radiographs of the same patient shown in Figure 13.9 after surgical correction and fusion with segmental pedicle fixation which has reduced the curve to 8 °.

Other methods of fixation and correction may be required for more severe curvatures, or when abnormal vertebral pathology exists, as in congenital curvatures which may include a kyphotic component.

Secondary structural scoliosis

In this group the spinal curvature is secondary to a demonstrable underlying abnormality.

Pathology. In congenital hemivertebra there is a sharp angulation at the site of the anomaly, with compensatory curves above and below (Fig. 13.7B). Scoliosis following poliomyelitis is explained by unequal pull of the muscles on the two sides. The mechanism of scoliosis complicating neurofibromatosis is not clear; in this type the deformity may be very severe.

Treatment. In most cases treatment is along the lines suggested for idiopathic scoliosis.

Sciatic scoliosis

Sciatic scoliosis is a temporary deformity produced by the protective action of muscles in certain painful conditions of the spine.

Cause. In many cases the underlying cause is a prolapsed intervertebral disc impinging upon a lumbar or sacral nerve. But the deformity may also be observed in some cases of acute low back pain p. 241, the pathogenesis of which is not entirely clear.

Clinical features. The predominant feature is severe back pain or sciatica, aggravated by movements of the spine (see prolapsed lumbar intervertebral disc, p. 236. The onset is usually sudden. The scoliosis is poorly compensated; so the trunk may be tilted over markedly to one side (see Fig. 13.27, p. 238. The curvature is not associated with rotation of the vertebrae.

Treatment. The treatment is that of the underlying condition.

TUBERCULOSIS OF THE THORACIC OR LUMBAR SPINE (TUBERCULOUS SPONDYLITIS; POTT’S DISEASE1)

Tuberculosis of thoracic or lumbar vertebral bodies was formerly one of the commonest forms of skeletal tuberculosis, and it is still prevalent in some Eastern countries, though now seen only rarely in the West.

Pathology. The infection begins at the anterior margin of a vertebral body, near the intervertebral disc (Fig. 13.12A). The disc itself is usually involved at an early stage. The extent of the destruction varies widely from case to case. Commonly there is complete destruction of one intervertebral disc with partial destruction of the two adjacent vertebrae, most marked anteriorly (Fig. 13.12B). But the changes may extend over several spinal segments; or, on the other hand, they may be confined to a single intervertebral disc, without evident bone involvement (Fig. 13.13A). Anterior collapse of the affected vertebrae leads to an angular kyphosis (Figs 13.12B, 13.13B and 13.14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree