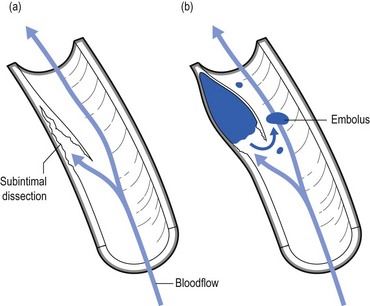

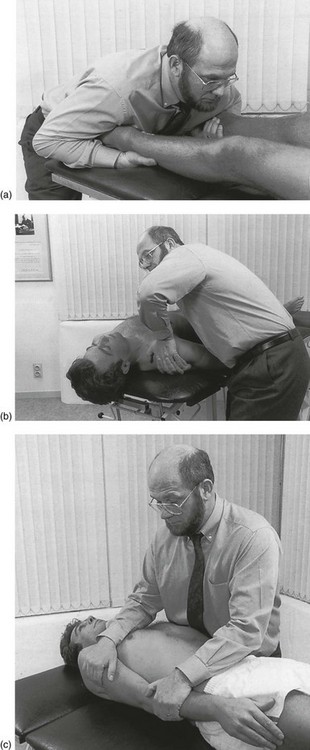

11 Cervical manipulations can cause severe neurologic complications, which are both exceedingly rare and generally unpredictable.1 More than 200 cases of more or less serious complications after manipulative treatment of the neck have been reported,2 but it is suggested that they are probably under-reported.3,4 Many authors have therefore become very cautious in accepting the suitability of this modality. The main arguments against manipulation are the possible hazards to the vertebrobasilar system and the spinal cord that are usually irreversible.5–10 Therapists who are familiar with manipulative techniques continue to use them because they consider the risks to be minimal. However, such conclusions can only be made after comparative scientific studies have proven that the benefits of manipulation outweigh the risks. Treatment decisions cannot be based on effectiveness data alone. Another important factor is safety, obviously. Weighing the risks of spinal manipulation against its benefits is therefore an exercise that should be done constantly. Every act in medicine, whether diagnostic or therapeutic, carries a risk of complications; an injection may result in an anaphylactic reaction, the use of anti-inflammatory agents may cause internal bleeding, and surgical procedures may lead to other, serious complications. It cannot be denied that spinal manipulation too, particularly when performed on the upper spine, is sometimes associated with adverse effects, which are usually mild to moderate. However, serious complications, such as vertebral artery dissection followed by stroke or death, myelopathy and epidural haematoma, have also been described. Mild side effects are very common. Surveys have shown that between one-quarter and one-half of all patients reported at least one post-manipulative reaction. The most common were headache, stiffness, local discomfort and fatigue.11,12 Most of these reactions began within 4 hours and generally disappeared within 24 hours of receiving spinal manipulation.13 The frequency of serious adverse events is difficult to estimate, but according to several publications it varies between 5 strokes/100 000 manipulations to 1.46 serious adverse events/10 000 000 manipulations and 2.68 deaths/10 000 000 manipulations.14–18 The complication that is feared the most is dissection of the vertebral artery, leading to infarction of the brain, cerebellum or brainstem, so-called Wallenberg’s syndrome (see online chapter Headache and vertigo of cervical origin). Furthermore, pulsatile pressure damages the muscular layer, resulting in a further splitting or dissection, extending in the direction of blood flow.19 The accrued blood soon develops into a thrombus and deforms the intima, pushing it into the arterial lumen. Blood flow in the cervical arteries can be obstructed either directly by the haematoma or indirectly by the detached emboli that move distally and obstruct the progressively smaller vessels in the brain, resulting in a stroke (Fig. 11.1).20 The cervical arteries are innervated with pain-sensitive nerve fibres that may generate neck pain and headache when provoked. Several studies have shown that pain is typically the first symptom associated with vertebral artery dissection (VAD), and a recent study reported that 8% of the patients presented with head or neck pain as their only symptom.21 Pain related to VAD frequently occurs suddenly and is of severe intensity, involving mostly the ipsilateral occipitocervical area. These symptoms may or may not be followed by ischaemic involvement in the brain, cerebellum or brainstem. The interval of time between the initial pain of VAD and the ischaemic symptoms is quite variable, with reports ranging from almost immediately to several weeks. Although the pathophysiology of a dissecting vertebral artery is well understood, the underlying cause of intimal tears remains uncertain. Most experts link VAD to trauma of varying degrees of severity and maintain that, because tearing occurs, previous trauma was necessarily involved.22 A retrospective analysis of 80 patients with vertebrobasilar ischaemia determined to be caused by frank neck trauma reported that 70 of the cases were related to motor vehicle accidents.23 However, VADs more commonly occur after very minor trauma and even after everyday activities that most people would consider to be non-traumatic. Examples of such trivial ‘trauma’ include countless everyday activities that involve head and neck movement, such as reversing a vehicle, coughing, vomiting, unusual sleeping positions, having one’s hair washed at a beauty salon, and rhythmic movement of the head and neck to music.24–26 One article listed 68 activities that have been implicated in the development of VAD.27 Another article reviewing 606 cases of VAD reported that 371 or 61% were spontaneous. The remaining 39% were associated with trivial or other trauma, which included manipulation in 9% of the total number of cases.28 So far it remains unclear what the exact precipitating cause of the development of a VAD might be. Given that many VADs are not related to trauma or even abrupt head movements, one must wonder whether a clear cause-and-effect relationship can be established in cases that involve mechanical triggers. It has been suggested that a mechanical trigger is only one of multiple components and that an underlying arterial abnormality is the predisposing factor to dissection.29,30 This opinion is based on several observations: first, many VADs are not related to trauma and simply occur spontaneously; second, VAD patients frequently have coexisting physiological abnormalities, such as hypertension, recent infection, migraine headache and several others; third, the average person is exposed to trivial events involving the neck on a daily basis, yet most people do not develop VAD. For the individual therapist who wants to exclude potential disasters, it is extremely important to determine the group of patients at risk and the kinds of manœuvre that are dangerous. Judging from the existing literature, it seems that at this time, neither is possible. Cerebrovascular accidents after manipulation appear to be unpredictable and should be considered an inherent, idiosyncratic and rare complication of this treatment approach.31 In a retrospective review, Haldeman and co-workers studied 64 medicolegal cases of stroke associated with cervical spine manipulation. The strokes occurred at any point during the course of treatment. Certain patients reported onset of symptoms immediately after the first treatment, while in others the dissection occurred after multiple manipulations. There was no apparent dose–response relationship to these complications. These strokes were noted following any form of standard cervical manipulation technique including rotation, extension, lateral flexion and non-force and neutral position manipulations. The results of this study suggest that stroke, particularly vertebrobasilar dissection, should be considered a random and unpredictable complication of any neck movement, including cervical manipulation. It may occur at any point in the course of treatment with virtually any method of cervical manipulation. The sudden onset of acute and unusual neck and/or head pain may represent a dissection in progress and be the reason a patient seeks manipulative therapy that then serves as the final insult to the vessel, leading to ischaemia.32 This puts another perspective on the relationship between cervical spinal manipulation and VAD: is VAD caused by the manipulation or is the patient manipulated because of incipient VAD?33 Although the risk of serious complications cannot be denied, it should be put into context. The incidence of VAD in relation to cervical manipulation remains very low. One Canadian survey, for instance, reported 23 cases of VAD after cervical manipulation over a 10-year period, representing a rate of 1/584 638 manipulations.34 Other publications estimate the incidence of VAD to be 1 in a million.35,36 Furthermore, several authors have made a comparison between the occurrence of injury following manipulation and the complications of other treatments for cervical disorders. The incidence of a serious complication such as a gastrointestinal event after the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is 1 in 1000.37 After surgical procedures to the cervical spine, 1.6% of complications occur. These figures can be used to argue that risks from other causes such as drug therapy can be between 100 and 400 times greater than after cervical manipulation.38 During recent decades, tests have been described to detect vertebrobasilar insufficiency in order to identify those patients who may be at risk of serious post-manipulation complications. These tests are based on the assessment that blood flow to the contralateral vertebral artery is decreased when the cervical spine is rotated and extended to one side.39,40 This is because, during rotation, the contralateral vertebral artery slides forwards and down, causing it to narrow. However, in normal individuals, collateral vascular supply by means of the circle of Willis is sufficient to assure blood flow and to prevent symptoms (see online chapter Headache and vertigo of cervical origin).41,42 Mainly under the influence of the Australian Physiotherapy Association, performing a vertebral artery test routinely prior to manipulation has become widely accepted.43–45 It is believed that the test could determine tolerance to cervical extension and rotation or could differentiate between dizziness caused by vertebrobasilar insufficiency and dizziness caused by other conditions, such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and inner ear pathology.46,47 Although prudent premanipulative testing seems to reduce the level of risk,48 both its validity and safety have recently been questioned.49 Premanipulative testing should not be considered as the ultimate safety precaution; studies have shown a high likelihood of obtaining false negative results, suggesting that the validity of the test is poor.50–53 Furthermore, it can even be argued that examination procedures are more dangerous than therapeutic manipulation, because the sustained posture required for the test exposes the patient to greater risk than a quick, high-velocity manipulation.54–56 The doctor or physiotherapist who intends to manipulate should always be aware that even tests during examination carry a risk and that there will always be a factor of unpredictability even when all premanipulative tests are negative and even if the patient responded positively to earlier manipulations. Screening for manipulative risks should not rely on the outcome of provocation tests but on the whole clinical picture that emerges after thorough history taking and clinical examination. In this perspective, a recent study that compared the results of a simple questionnaire to a duplex Doppler ultrasound demonstrated excellent sensitivity (1.00) and good specificity (0.78).57 The questionnaire consisted of the following: ‘Do you avoid looking up as if into a high cabinet shelf because doing so causes neurological symptoms such as: visual problems, dizziness, unsteadiness, confusion, headaches and symptoms in the extremities?’ The same question was posed in relation to turning the head to the right and to the left, as if reversing a car. Review of the literature, especially of the many case histories that have been described, also leads to the conclusion that a number of serious complications could have been prevented had practitioners recognized warning signs which should have led them to exclude manipulation.58–60 One review mentions faulty diagnosis, insufficient clinical knowledge or examination, inaccuracy as a result of routine, overconfidence, bad technique and therapeutic obstinacy as the main causes of complications.61 In recent years another view of the relationship between cervical manipulative therapy and VAD has emerged. The relationship was usually seen as simple cause and effect, in which manipulation causes a dissection in certain susceptible individuals. Recent evidence, however, suggests that the relationship is not causal, and that patients with VAD often have initial neck symptoms which cause them to seek care; they then have a stroke some time later, independent of the treatment. This new understanding has shifted the focus for the therapist from one of attempting to ‘screen’ for ‘risk of complication with manipulation’ to one of recognizing the patient who may have a VAD so that early diagnosis and intervention can be pursued.62 Again, this recognition can only be achieved by looking at the complete clinical picture and by following the proper diagnostic procedures (Box 11.1). A posterocentral disc displacement that is left untreated exerts constant pressure against the posterior longitudinal ligament. It may slowly become larger or give rise to an osteophyte in the spinal canal as a consequence of ligamentous traction. When the bulge enlarges it may eventually compress the spinal cord as well as the anterior spinal artery (see p. 165). The symptoms and signs elicited may finally become irreversible. For all these reasons it is unwise to leave an early minor disc displacement unreduced. Everyone who undertakes manipulation sees good and sometimes spectacular results in daily practice. This is somewhat in contradiction with the results that often emerge from randomized trials.63,64 The discrepancy is mainly caused by the fact that, in most of the studies, subgroups of patients are not well defined. Prospective randomized trials that take more care with inclusion and exclusion criteria usually result in a stronger trend favouring manipulation. Koes and colleagues, for example, performed a randomized trial on back and neck pain and found promising results for manual therapy and physical therapy in subgroup analyses of patients with neck pain.65,66 Hoving et al conducted a randomized, controlled trial of manipulation, physical therapy, and continued care by a doctor, which confirmed the superiority of manual therapy over physical therapy and continued care.67 Other authors studied the cost-effectiveness of manipulative treatment. The cost-effectiveness ratios and the cost-utility ratios showed that manipulation was less costly and more effective than physiotherapy or general practitioner care. The manual therapy group showed a significantly faster improvement than the others, with a total cost of less than one-third of that of physiotherapy and general practitioner care.68 Other randomized clinical trials in patients with mechanical neck pain confirmed clinically and statistically significant short- and long-term improvements in pain, disability and patient-perceived recovery when treated with manipulation.69–71 In orthopaedic medicine the utmost precautions are taken to avoid any possible complication. Therefore the therapist must follow a strict routine (see Box 11.1). First of all, there should be a firm clinical diagnosis, if necessary confirmed with technical investigation. Warning signs and contraindications are heeded. Manipulation is only considered if there is an unambiguous indication for it. Prognosis is determined and, if provisionally positive, manipulation is begun with strict methods. The manipulator will only proceed when sure of personal skill. During each manipulative session, constant reassessment is made and the decision as to whether or not to continue is totally dependent on the response obtained so far. The results of the examination, both positive and negative, are then interpreted in the light of anatomical reality (see p. 181). Correlation between history and functional examination is sought (inherent likelihoods): does the behaviour of the pain (onset and evolution, referred versus local) and the paraesthesia (development, presence and pattern) match the clinical findings? Examination features are related to possible articular, root or cord origin. Articular signs are mirrored by specific patterns of limitation. Root involvement may be obvious from motor or sensory deficit or disturbances of reflexes. Evidence of cord involvement is revealed by particular patterns of neurological presentation. • The dura mater and/or dural nerve root investment. Multisegmental pain and tenderness show the dura mater to be affected; pure segmental pain points towards the investment of the nerve root. Scapular pain on coughing is considered to be a dural symptom. • The intervertebral joint. An asymmetrical pattern of pain and/or limitation (‘partial articular pattern’) indicates internal derangement in the intervertebral joint. Other features are pain on movement and/or posture, twinges and, in more acute examples, deviation of the head. • The nerve root parenchyma. Segmental (dermatomal) paraesthesia may accompany the root pain. Neurological deficit (motor, sensory and reflexes) is often present. • The spinal cord. Multisegmental paraesthesia in the hands and/or feet is provoked by neck flexion; other signs of motor and/or sensory tract involvement may also be found. During history taking and functional examination, the examiner must remain alert and constantly aware so as not to overlook possible warning signs (Box 11.2). The presence of any one of these red flags indicates a non-mechanical lesion and is an absolute bar to any active treatment. The patient should be referred for further investigations immediately. It is crucial to know when a manipulation is unsafe. In this regard, data collected from history and clinical examination are far more important than the outcome of one or more premanipulative tests (see p. 183). Great caution should therefore be observed in detecting potential contraindications during history taking and functional examination (Box 11.3). The moment that there is clinical evidence of an upper motor neurone lesion, manipulation must be abandoned. Symptoms are: paraesthesia in the hands and/or the feet influenced by neck flexion.72 Signs are: positive plantar reflex, positive Hoffman sign, spasticity and incoordination. This condition can lead to ligamentous laxity at the upper cervical joints, which creates an absolute contraindication to manipulation.73 The typical soggy end-feel puts the examiner on his/her guard.74,75 It is unwise to manipulate a patient who is on anticoagulant therapy because of the danger of an intraspinal haematoma.76 Only if the therapy can be stopped for the duration of treatment is manipulation possible. In the inflammatory stage of ankylosing spondylitis or in the unlikely event of a patient with this disorder developing a disc lesion, manipulation is not at all safe, especially in the cervical spine, where luxations, fractures and cord compression have been described.77,78 Posterocentral disc protrusions Rotation techniques are contraindicated. The larger the protrusion seems to be, the more the manipulator resorts to techniques without articular movement. Techniques are used under considerable traction, the effects of which help to reduce the fragment of disc (see p. 196). Acute torticollis in patients under 30 years Muscular guarding renders manipulation under traction in the direction limited by spasm impossible. Because the condition is the result of nuclear prolapse, the very restricted rotation and lateral flexion initially present are increased by gently sustained pressure. Restoration of movement is thus achieved (see p. 196). Significant deviations of the cervical spine, either in side flexion or in flexion, make manipulation under traction impossible. Before the usual techniques can be used, the manipulator must bring the patient’s head back to the neutral position. This happens after repeated tractions (whether or not with manipulative thrust) in the line of the deformity (see p. 196). It is not enough to have excluded warning signs and contraindications. It is just as important to make sure that a clear indication is present: a posterocentral or posterolateral disc protrusion causing a discodural or discoradicular interaction (Box 11.4). Acute torticollis with side flexion deformity A distinction is made between torticollis in the young (under 30 years old), which is usually of the nuclear type, and that in those over the age of 30, who suffer a cartilaginous displacement (see p. 196). • When severe scapular pain has remained after the root pain began: usually the scapular pain and the articular signs disappear or considerably diminish when brachial pain occurs. In the rare event that some movements remain limited and cause severe pain in the scapular area, especially at night, one manipulative session may abolish the scapular pain and restore a full painless range of movement. The root pain remains unaltered and continues its spontaneous course (see p. 157). • When root pain lasts for a considerable period: most root pain progresses to full recovery in the course of 3–4 months – except C8 pain, which may take up to 6 months to recover. Occasionally a patient may be seen with root pain that has lasted longer than 6 months, even up to 1 or 2 years, and investigation has not shown a neuroma or other similar lesion. Manipulation will not immediately influence the root pain; however, a few days after manipulation, the pain starts to diminish and after a second treatment 2 weeks later all symptoms may disappear. This peculiar clinical phenomenon could be explained by the concept that, although manipulation shifts the discal rim back immediately, it takes some time for the swelling and inflammation to abate and thus for pain to diminish.79,80 Before manipulation is decided upon, the chances of success should be assessed by considering the following questions. By answering these four questions one can make a reasonable prognosis for a number of clinical situations (Box 11.5).81 A central protrusion with spinal cord compression is potentially dangerous and any sign – positive plantar reflex, spasticity, incoordination, gross weakness – must therefore be considered as an absolute bar to manipulation (see p. 185). When movements affect scapular pain, this is considered as ‘favourable’ and manipulation has a fair chance of success. Circumstances in which neck movements augment root pain have to be regarded as ‘unfavourable’, as the result of manipulation is usually inferior (see p. 187).

Treatment of the cervical spine

Treatment of discodural and discoradicular interactions

Manipulation

Controversy

Dangers of manipulation

Vertebral artery dissection

Premanipulative testing

Dangers of not manipulating

Evidence: results

Precautions

Proper interpretation of the examination (clinical reasoning)

Diagnosis: discodural or discoradicular interaction

Exclusion of warning signs

Exclusion of contraindications

Absolute contraindications

Relative contraindications

Recognition of a clear indication

Posterocentral discodural interaction with unilateral cervicoscapular pain

Posterocentral discodural interaction with central neck pain or bilateral cervicoscapular pain

Posterolateral discoradicular interaction with unilateral root pain, without neurological deficit

Prognosis: criteria of reducibility – presence of favourable or unfavourable signs

Is the protrusion central, unilateral or bilateral?

Is the pain influenced by articular movements?

Manipulation technique