Chapter 29 Treatment of Juvenile Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans (JOCD) is a condition in which a portion of subchondral bone and its overlying cartilage become damaged; it usually affects the knee.* This results in a spectrum of pathology beginning with a lesion to the bone only, followed by eventual cartilage separation, bone separation, and loose body formation.

JOCD may result in myriad nonspecific clinical symptoms, ranging from mild pain to joint effusion to locking,13,31,38,55 which can complicate the diagnosis. Furthermore, the cause of and most effective treatment for osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) and JOCD still remain largely unclear today because of conflicting reports, studies that combine lesion types, small study population sizes, and short follow-up periods.7,9,23,78 Regardless, treatment should seek to prevent early-onset osteoarthritis, which is associated with unhealed lesions and may show favorable results in up to 77.7% of cases.1

History

Osteochondritis dissecans exists in both juvenile and adult forms, distinguished as originating before or after closure of the distal femoral epiphysis, respectively.12,73 Cahill and Ahten10 have proposed a further subdivision of quiescent JOCD (QJOCD) as an asymptomatic form of JOCD, which will become symptomatic if left untreated.

Paget first described OCD in 1870 as resulting from a “quiet necrosis” of the bone.65 It was König, however, who named the condition osteochondritis dissecans in 1887, under the false impression that the lesion arose from an inflammatory process.47 König later rejected this hypothesis, but the misnomer remained.4

Epidemiology

It is difficult to determine the true prevalence of JOCD largely because papers tend to report OCD and JOCD cases as single populations.9,12,23 The lesion may also be confused with normal variants in ossification, which could lead to over- or underreporting of its true incidence.30 Finally, patients with JOCD often wait several months before seeking treatment, leading some to speculate that many lesions may heal spontaneously and hence will never be diagnosed. Most authors agree, however, that the condition is relatively uncommon.13

Historically, more boys present with JOCD than girls; the ratio of boys to girls affected ranges from 2 : 1 to 3 : 2, although this seems to be decreasing.3,9,23,38,39 The average age of children afflicted with JOCD is reported as between 11.3 and 12.9 years.13,69,83 This, too, seems to be changing; some have noted that the average patient age has gone down in recent years.

Right and left knees are affected in approximately equal proportions, although some report a slight preponderance for right knee involvement.38,61 Bilateral lesions have been reported in 21.1% to 47% of affected children.11 Lesions tend to be located in the medial femoral condyle, with most being in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle.3,13 Lesions in the central and medial aspects of the medial femoral condyle are somewhat less common. The lateral femoral condyle has been reported as the lesion site in 15% to 16.5% of cases. The patella tends to be involved less often, with reports ranging from 4.8% to 6.5% involvement. Lesions have also been reported in the tibial plateau, the entirety of the femoral trochlea,72 and both the lateral and medial condyles of a single femur,35 although these are not common findings.

Cause

There is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the cause of JOCD, and many theories have attempted to explain the condition.9 König initially described OCD as stemming from inflammation, but even König himself has rejected this theory since its first proposal4,47 because no evidence of inflammation had been noted.25

It has also been suggested that aseptic necrosis is responsible because of a proposed poor blood supply to the medial femoral condyle.31,70 Another report, however, found no evidence of necrosis in excised OCD lesions, challenging this idea.14

Some studies have postulated that there is a familial form of OCD, with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.34,60,64,68,75 Petrie,67 however, conducted a study of 86 first-degree relatives in 34 patients with OCD lesions and found only one relative who also had the disease. Additionally, Hefti and colleagues38 have found that only 4.2% of their 452 patients with OCD reported having family members with the condition. It is possible that conditions such as multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, which has both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns, may be mistaken for familial OCD.15 Various other theories for the cause of JOCD have been proposed, including links to embolism,25 ossification abnormalities,71,73 patient height, endocrine dysfunction, and Osgood-Schlatter disease, but these hypotheses have not been well supported.61,67

The remaining proposals largely center on some type of trauma as the cause of JOCD. Fairbank25 has suggested that the lesion results from internal tibial torsion, which drives the tibial spine into the femoral condyle thereby causing a fracture, leading to OCD. A more recent study by Bramer and associates6 have shown that individuals with OCD have a significantly greater degree of external tibial torsion as compared with unaffected individuals.

These theories have been questioned, however, because several studies have observed large percentages of lesions in areas that could not have been from such an injury.41,61 Additionally, direct trauma is reported in only 21.2% to 46% of patients with OCD or JOCD and in less than 10% of patients with JOCD.3,10,38,83

The currently prevailing theory relates JOCD to repetitive trauma. Several reports have supported the idea that repeated microtraumatic events lead to stress fractures in the subchondral bone, compromising vascular supply to the area and causing lesion formation.3,9,10,12,40,48 This is supported by the observation of joint deformities in several patients, which may increase joint stress and the location of many lesions in weight-bearing areas of the knee. The theory is further strengthened by the fact that many JOCD sufferers are active athletes,23,25,38,41,83 although it is questionable whether they are significantly more active than their unaffected peers.61

Finally, there may be a link between JOCD of the lateral femoral condyle and discoid meniscus, with speculation that the altered meniscus has a decreased capacity to absorb loads.19,37,74 This lends further support to the microtrauma theory.

Prognostic Indicators

JOCD lesions tend to show greater healing rates than OCD lesions.7,38,42,69 Additionally, younger children may show an increased propensity for healing than older children, although this has been challenged.78 It is generally accepted that smaller JOCD lesions have a greater ability to heal than larger lesions12,62 and that unstable lesions have a poorer prognosis than stable lesions. Despite these generalities, each theory has been questioned.45,79 Although many have speculated that lesion location may be related to prognosis, reports vary38,45,62,69,83; thus, it seems best to disregard location when determining a patient’s outlook.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Early JOCD lesions tend to show nonspecific symptoms, such as pain, swelling, and quadriceps atrophy.13,38,55 Later lesions may show more severe symptoms, including limping, effusion, decreased range of motion, and locking, especially if loose bodies are present. Even with such varied symptoms, Green and Banks31 have observed no clinical abnormalities in half of their 27 patients. Similarly, physical examinations for JOCD tend to yield few definitive results. Palpation may elicit tenderness, although this has been reported in from 36.2% to 74.6% of patients.

Wilson80 has indicated that children with JOCD may walk with their ipsilateral foot laterally rotated to relieve pain from contact between the ACL, tibial spinous process, and lesion and described a technique for using this finding to diagnose JOCD. The patient lies supine and the knee is flexed by the examiner to 90 degrees; the tibia is medially rotated and the knee is extended, which should elicit pain that is relieved with lateral rotation or successful treatment. Unfortunately, a more recent study found the test to be positive in only 25% of 32 cases of known OCD.16

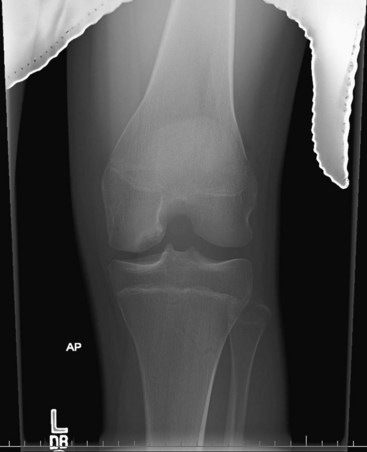

Therefore, imaging studies may be the best means of diagnosing JOCD. Anteroposterior, lateral, skyline, tunnel, and notch radiographs are always indicated to detect the presence of a bony lesion11,31,36 (Fig. 29-1).

Many have advocated the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to visualize the cartilaginous aspects of the lesion to determine its size.* MRI may also be useful in ascertaining lesion stability and prognosis, because lesions surrounded by a high T2 signal intensity line may be unstable, particularly if the line has the same intensity as the joint fluid around it, is surrounded by a second low T2 intensity line, is present along with breaks in the subchondral bone plate as seen on T2-weighted MRI, or is surrounded by cysts.83 Dipaola and coworkers22 noted a better correlation between MRI and arthroscopic staging than between radiographic and arthroscopic staging, suggesting that MRI is a superior technique. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI may further aid in diagnosis49 (Fig. 29-2).Cahill and colleagues9,11,12 have recommended the use of technetium scans to determine the healing status of the lesion and rule out normal ossification variants as potential JOCD lesions, but not to ascertain lesion prognosis. Cepero and associates13 have also suggested that computed tomography (CT) scans are helpful for discerning the extent and location of JOCD lesions, especially in younger patients who might have difficulty staying still for an MRI. Regardless of the study, normal ossification variants common in the femoral condyles of children may resemble JOCD lesions.8,30 Thus, care must be taken when interpreting images to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

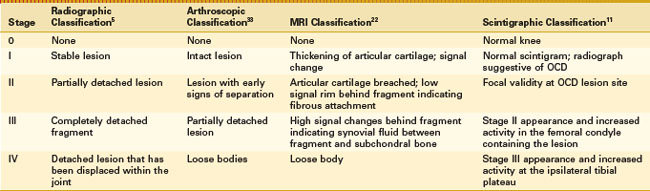

To further assist with assessing OCD lesion prognosis, several classification systems have been developed; these are summarized in Table 29-1.

Treatment

Untreated JOCD lesions have been shown to lead to early-onset osteoarthritis; treatment is aimed its prevention.1,7 Although many treatment options exist for JOCD, they are difficult to evaluate because authors often mix OCD and JOCD and stable and unstable lesions into the same study populations.9,78

Initial Management

In spite of the mixed study population, there is a general consensus that stable JOCD lesions should initially be managed nonsurgically.38 Whether this management should include immobilization or continuous motion is uncertain. Healing has been reported in up to 50% of JOCD lesions at an average of 10 months after management by restricting activities, but not mobility or weight bearing.9,10,12 Others have also found good results with similar activity modifications and quadriceps exercises to avoid quadriceps atrophy, stiffness, and potential cartilage degeneration that may be associated with immobilization,3,16,83 as noted by Hughston and coworkers.41

In contrast, several studies have recommended that conservative treatment include some form of immobilization. Green and Banks31 reported excellent results in 17 of 25 knees that were kept in braces or casts. Others have also found favorable results following treatment with a cast69 or cast followed by a brace.78 In spite of these differing theories, Hefti and colleagues38 were able to find no statistically significant difference between a number of conservative treatment methods used for 154 patients in their study, which included the use of casts and braces, no treatment, or physical therapy.

It is important to note that noncompliance may be a significant hindrance to successful conservative treatment, especially among the active population typically affected by JOCD. This has prompted some to recommend a shortened period of conservative treatment followed by surgery, which has shown positive results in this group.10,23,38 Similarly, Cepero and associates13 have reported that 89.5% of their 67 patients required surgical intervention and that compared with conservative management, arthroscopic treatment decreased clinical healing time by an average of 4.8 months and radiographic healing by an average of 3.4 months.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree