Abstract

First created in 1996, the French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units (UEROS) now play a fundamental role in the social and vocational rehabilitation of patients with brain injury. As of today, there exist 30 UEROS centers in France. While their care and treatment objectives are shared, their means of assessment and retraining differ according to the experience of each one. The objective of this article is to describe the specific programs and the different tools put to work in the UEROS of Limoges. The UEROS of Limoges would appear to offer a form of holistic rehabilitation management characterized by the importance of psycho-education and its type of approach towards vocational reintegration.

Résumé

Les unités d’évaluation, de réentraînement et d’orientation sociale et professionnelle (UEROS), créées en 1996, sont actuellement des dispositifs fondamentaux pour la réinsertion socio-professionnelle des patients cérébrolésés. À ce jour, elles sont au nombre de 30 sur le territoire français. Elles ont en commun leurs objectifs de prise en charge, mais leurs moyens d’évaluation et de réentraînement varient en fonction de l’expérience locale. L’objectif de cet article est de décrire les programmes et les outils mis en application au sein de l’UEROS de Limoges. Il apparaît que l’UEROS de Limoges propose une réhabilitation holistique, dont les spécificités sont la place de la psycho-éducation et le type d’approche de la réinsertion professionnelle.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units (UEROS) are organizations specifically designed for patients with traumatic brain injury, and their stated objective is “to upgrade medico-social management of this population in view of favoring genuine social and vocational reintegration”.

They were brought into being by a 4 July 1996 circular assigning them four distinct missions:

- •

precise assessment of the somatic and the psychic sequelae in the injured person and of his principal potentialities in terms of subsequent social, educational or professional rehabilitation;

- •

elaboration of a “transitional program of retraining for his return to active life”;

- •

establishment of communication involving the injured person, his family and the various institutional interlocutors (attendant physicians, the departmental homes for the disabled known as maison départementale des personnes handicapées [MDPH]);

- •

personalized follow-up and assistance along the path to employment.

The terms of this circular were speedily implemented, and UEROS facilities have emerged throughout France according to the different environments and means placed at their disposal . And so, even though they all share the same objectives, the 30 existing UEROS centers differ and vary in their actual functioning.

A 17 March 2009 decree enlarged the potential population of the UEROS establishments by opening them to any person presenting cognitive, behavioral or emotional disorders connected with “traumatic brain injury or any other acquired cerebral lesion”. The decree was aimed at standardizing UEROS functioning, and stated that assessment “had to be carried out at least at the outset and the end of retraining and, if at all possible, in a real-life setting”. As for the retraining program, the contents were not elaborated in detail, but it has got to include “assessments, workshops, and the phasing-in of simulated familial, societal, educational and vocational situations”.

The French inter-federal group responsible for statistical evaluation regularly provides a qualitative as well as quantitative analysis of the UEROS facilities centered on the overall functioning of the structures and their results in terms of their activities, trainee outcomes and the follow-up they offer. On the other hand, the specific characteristics of the different UEROS centers and their rehabilitation programs are not widely known. One example of the functioning of a regional network for brain-injured patients has been described by the Nord Pas de Calais team . Two experiences in overall UEROS management, those of Mulhouse and Bordeaux , have been the subjects of detailed study in the literature. As regards trainee outcomes, the only available results, which date back to 2007, are those pertaining to the Aquitaine UEROS .

The objective of this work is to describe the rehabilitation program presently carried out at the Limoges UEROS.

1.2

The place of the French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units in the health care network

In the French Limousin region, the small scale of the existing structures facilitates coordination of the different health care providers dealing with brain-injured patients.

During the acute phase of head injury, treatment generally occurs in the intensive care and neurosurgery units of the Limoges-based regional university hospital. Post-acute care initially takes place in the psycho-rehabilitation department, which is associated with the Esquirol psychiatric hospital. This postoperative and recuperation facility includes a recovery ward, a brain injury inpatient rehabilitation unit, a unit dedicated to chronic vegetative patients and a brain injury day-patient unit. The four structures are all located in the same wing.

Following post-acute rehabilitation, the most severely impaired patients may carry on rehabilitation in the day-patient unit, while the others undergo outpatient rehabilitation. Furthermore, a mobile team specialized in brain trauma care may intervene wherever a patient resides for purposes of reeducation and rehabilitation.

As regards social and/or vocational reintegration, two structures, both of them found in the Esquirol hospital, are regularly called upon:

- •

the Limousin-based brain injury network helps the patient manage his social and vocational activities both at home and at the workplace;

- •

the Limoges UEROS.

The UEROS structure involves a coordinator (an ergonomics psychologist), two occupational therapists, a neuropsychologist, a social worker, a secretary, a social and family finance counselor, an occupational psychologist and a medical consultant. The process of admission to the Limoges UEROS is equally applied at other UEROS establishments. Preadmission procedure consists in consultation with a physician in the psycho-rehabilitation unit, an interview with the UEROS coordinator and another interview with the social worker. An application is subsequently sent to the departmental house for disabled persons [MDPH], which facilitates orientation towards a UEROS unit. So as to reduce waiting time, the patient is immediately registered on the UEROS waiting list, which generally contains 10 to 20 requests. A visiting day allows the UEROS team to meet the future trainee and decide on the course of action to be undertaken: no management indicated, a simple evaluation or an evaluation followed by a UEROS training program. If the MDPH decides upon a UEROS orientation, 3 to 6 months later the patient is admitted to UEROS as a vocational trainee. From admission onwards, one of the staff members takes on supervisory functions so as to guide him and those close to him throughout the training and ensure long-term follow-up.

The Limoges UEROS was created in 1997 and is accredited to host six trainees at the same time. Between 2005 and 2008, those admitted were predominantly male (82.4%), relatively young (mean age = 31.5 years), traumatically brain-injured (82%) and of a low pretraumatic educational level (74%). They presented with moderate (80%) Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) 2 to severe (20%) GOS 3 disability. Strokes were the second most frequent cause for disability (9.5% of the cases); other causal pathologies included tumors, encephalitis, cerebral anoxia and epilepsy. UEROS management generally got underway well after the traumatic event: only 32% within 2 years, 48% from 3 to 10 years later, and 16% more than 10 years subsequent to the brain injury.

1.3

The Limoges French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units programs

Through development of a holistic approach , programs take into account a person considered in his entirety and target “ecological” objectives close to his actual experience.

An evaluation phase leads to definition of a set of objectives that will serve as guidelines during a retraining phase aimed at social and vocational reintegration.

Sustained support is designed to enable the trainee to draw a connection between his condition before and after the traumatic event and to thereby develop awareness of not only his difficulties but also his potentialities and go on to adopt a realizable project and find the means to see it through.

1.3.1

The evaluation

The evaluation phase is standardized and lasts four weeks.

Medical, neuropsychological, occupational, psychological, social and vocational evaluations take place over the same time period. In typically analytical approaches, neuropsychological test results constitute the first step towards the determination of objectives and reeducation management strategy. In the UEROS approach, on the other hand, impairments are initially observed in an ecological situation. Only afterwards will neuropsychological test results serve to interpret the mechanisms of the disorders and help to orient the choice of compensation strategies that will be brought to bear in daily life.

1.3.1.1

The medical evaluation

The medical evaluation is performed at the outset by the Physical and readaptation medicine (PRM) hospital practitioner serving as coordinator of outpatient care, takes place in the presence of a UEROS staff member and is based upon the European Brain Injury Scale (EBIS) . The attendant medical recommendations, whether they involve therapeutic adaptations or supplementary explorations, will be applied over the course of the training program. After discharge, the same coordinating physician will systematically provide follow-up consultation.

1.3.1.2

The neuropsychological evaluation

The initial interview is devoted to reconstitution of the trainee’s medical history and personal biography. Cognitive evaluation is then carried out with standard tools. At the outset, global efficiency is assessed by means of the WASI-IV scale. The different memory capacities are quantified by the memory span measured in the MEM III test, the Grüber and Buschke test, the California Verbal Learning test and the Baddeley Doors and People test. The Rey Figure test is likewise administered. Attentional abilities are evaluated by the Zimmermann and Finn neuropsychological test battery, the D2 test and the BAMS-T. Language use is assessed by the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE), the Deloche and Hannequin oral denomination test (DO 80) and verbal fluency exercises. Praxia and gnosia are subjected to exploration only if need be. Executive functions are evaluated by means of the Trail Making test, the Martin shopping test, Shallice’s Six Element test, the Wisconsin Card Sorting test and the Tower of London test.

Neurobehavioral evaluation is performed with the GREFEX dysexecutive syndrome battery . The relevant data are collected by the neuropsychologist and the occupational psychologist.

Ecological evaluation is based on the Multiple Errands Test (MET) elaborated by Shallice and Burgess in 1991 , which is administered in a specially adapted form on a shopping street not far from the UEROS premises.

Specific cognitive objectives are determined once the neuropsychological evaluation process has been completed.

As a step towards retraining, as soon as the patient is admitted, his work on a date book serving as a memory aid gets underway.

1.3.1.3

The occupational evaluation

This evaluation focuses on the functional impact on daily life of the cognitive impairments; it consequently deals with everyday activities and consists largely in ecological tests.

During the initial individual interview, the trainee is asked to assess his degree of autonomy in daily life and, more precisely, to describe a day typifying the rhythm of his usual routine. His educational level is assessed through testing devised by the French distance learning school (CNED) and, if necessary, ascertained by the online learning portal of the French public education regional organ (GRETA). This evaluation of the trainee’s knowledge, abilities and vocational experience is supplemented by the EVAL3 software .

In addition to this psycho-technical evaluation, we carry out a functional evaluation involving several routine, “ecological” tasks: use of a phone book, a calendar, a washing machine; dealing with administrative documents and orienteering; woodwork and cooking. The cooking session is assessed according to widely used criteria. The trainee selects his menu, draws up a shopping list, makes a price estimate and plans out the meal itself (tasks to undertake/instructions to give, time management). In some cases, particularly when the trainee’s chosen vocational orientation is cooking-based, culinary therapy testing is carried further, with a video recording meant to foster impairment awareness and to facilitate the upcoming retraining program.

Sports abilities are also specifically evaluated. Individual physical drills are designed to assess motor skills, while team sport activities necessitating cognitive and behavioral adaptation are videotaped. Grading is qualitative as regards adaptation, memory, self-control, initiative, motivation and respect for both the rules of the game and for fellow players, while it is quantitative as concerns the different aspects of motor skills, ranging from 0 (no difficulty) to 4 (extreme difficulty).

This phase of evaluation is concluded by establishment of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) quotation, which is commonly employed as a medico-social reference.

1.3.1.4

The psychological evaluation

An interview with the clinical psychologist of the medical network allows for assessment of the psychological repercussions of the traumatic event and its impact on the trainee and his family. The trainee is constantly reminded of the psychologist’s availability throughout the training period. Outpatient intervention is offered if need be.

1.3.1.5

The social evaluation

The social worker assesses where the trainee stands in society and pays particular attention to his degree of autonomy in everyday organization and money management. If necessary, the social worker contacts the relevant social protection and outpatient social welfare services.

1.3.1.6

The vocational evaluation

Carried out by the occupational psychologist, the evaluation consists firstly in a one-hour clinical interview and secondly in creation of a “portrait” of the trainee over eight hours by means of a tool created at the Limoges UEROS. It is supplemented by two standardized tests: Holland’s personality inventory and the French classification of professional interests .

Designed to delineate a person’s identity, the “portrait” is composed of ten parts:

- •

after indicating his civil identity and level of studies, the trainee describes the circumstances surrounding his traumatic event and distinguishes what he wishes from what he does not wish to divulge to a future employer;

- •

he then gives definition to his personal objectives and their underlying motivations;

- •

after that, in the part entitled “who I see and how I represent work”, he enumerates the professions exercised by those around him and states how he perceives them (attraction or lack of interest);

- •

the trainee is then provided with an opportunity to retrace his life story by placing on parallel tracks his personal or emotional pathway and his educational and vocational pathways. The aim is to observe his professional itinerary through the lens of key events in his life and thereby better comprehend his personal development and reestablish a continuum between his life prior to brain injury, what happened in the aftermath, and his projects yet to come. For the benefit of trainees who immediately feel comfortable with this approach, the pathway is presented as a “frieze of life”. This part of the portrait should be seen not only as a skills assessment but also as a psychodynamic translation of a personal career path. It may likewise be considered as an approach taking the trainee’s identity into account in such a way as to allow him to achieve grounding in reality without being drawn back to the past;

- •

the work placements once carried out by the subject are inventoried, as are the subjects piquing his interest at school and the skills he acquired outside the educational system. Once he perceives his different learning experiences from a distance, he is called upon to pinpoint his strengths, which will bolster his self-image, along with his weaknesses, of which he shall remain aware throughout the training period;

- •

the same approach is implemented with regard to the different jobs held by the subject, the aim being to determine the main lessons to be drawn from these professional steps and stages. If need be, the social worker will supplement the job list with the corresponding pay slips;

- •

in this part, extracurricular activities and personal accomplishments are highlighted;

- •

these elements and items shall all contribute to the elaboration of a standard résumé in chronological order;

- •

the trainee will then proceed to an assessment of his present-day physical, intellectual, social and overall personal skills;

- •

the ultimate phase of “portrait” building consists in elaborating a realistic vocational project. While the portrait has been sketched out in detail during the evaluation, it will be finalized only over the course of the retraining period.

1.3.1.7

Conclusion and report on the evaluation

The evaluation is concluded by determination of the MPAI quotation , which is a standardized medico-social clinical reference assessing initial physical and cognitive skills, along with the capacity for adaptation and participation that will condition social reintegration.

The different members of the staff help to define the objectives of the training period and go on to provide the trainee with feedback on the evaluation and the objectives, which are subsequently discussed individually with the UEROS coordinator and the neuropsychologist. In close conjunction with the trainee, they think over the objectives so as to set up milestones in the reintegration process and underscore the overall purpose of the project. The objectives also constitute material facilitating coping and paving the way to acceptance of accident sequelae.

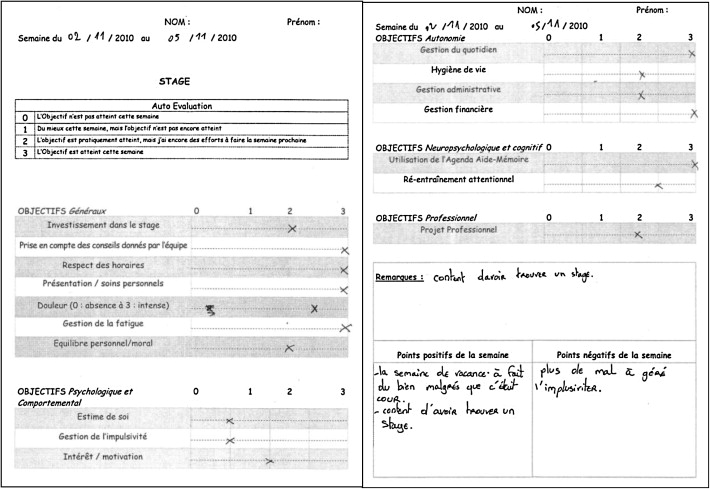

The trainee is asked to note his objectives in his training record booklet, which he will use throughout the training period as he puts into writing his accomplishments, his observations and a running commentary. The booklet will attest to the pathways taken by the trainee, and they will enable him to assess his development in terms of the goals to be reached and, more specifically, as regards his accomplishment of the personal project ( Fig. 1 ).

A written report on the evaluation results will be sent to the attendant physicians and to the MDPH, and will also be explained to the trainee’s relatives.

1.3.2

The retraining

Retraining is carried out over 20 weeks and consists in cognitive retraining, behavioral retraining, autonomy reinforcement, and vocational reintegration involving professional retraining.

The functioning of our UEROS center is based above all on tram dynamics. Its nine members are in constant interaction and work in pairs when conducting group sessions. In addition, weekly staff meetings facilitate overall assessment of each trainee’s ongoing development. This way of functioning likewise facilitates elaboration of both a socio-professional project and a retraining program that is at once comprehensive and individualized.

During individual sessions the trainee works through the difficulties specific to him, becomes increasingly aware of his impairment, and comes to terms with his disabilities as he lays emphasis in his residual abilities. During group sessions, the strategies brought into being with regard to the trainee are applied, and the feedback emanating from peers helps to further social reintegration.

1.3.2.1

Cognitive retraining

1.3.2.1.1

Conventional cognitive retraining

Conventional cognitive retraining plays only a minor role in the Limoges UEROS, which prefers to emphasize more ecological tasks. Its development is contingent on understanding of the difficulties outlined and underlined in the initial neuropsychological evaluation. Retraining should be apprehended as global, and it is built around attention skills and working memory. It is carried out in a standard manner with paper-and-pencil tests, and also with dedicated software: span forward exercises, word arranging, acronyms, N-back task, attentional retraining with the help of GERIP ® software, utilization of Tap-Touche ® software in occupational therapy. Particularized retraining is carried out on a case-by-case basis with regard to specific cognitive impairments such as visuo-constructional disorders that entail major consequences in daily life.

1.3.2.1.2

Practical applications

In all cases, emphasis is laid on regular use of the date book, which serves as a memory aid. Different technical workshops are propitious to the implementation of compensatory strategies: gardening, culinary therapy, journal workshop, woodwork, wickerwork, cardboard or mosaics… Sustained focus on concrete tasks tends to enhance trainee involvement and adhesion.

1.3.2.1.3

Psycho-education through “stimulation groups”

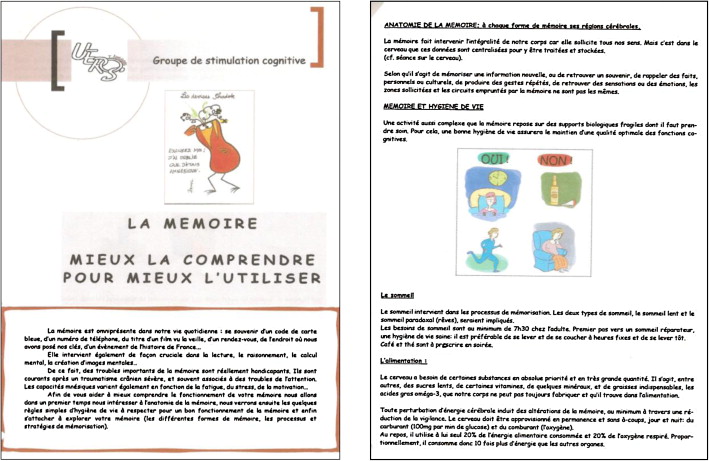

From the very outset, we strongly encourage investment of the trainee in his retraining program. One of the factors limiting investment is the difficulty encountered by trainees in their apprehension of the brain itself with its structures and functions; as a result, they are ill-equipped to analyze the consequences of their brain injury, not to mention the objectives put forward by the UEROS center. That is why we have elaborated an educational program dealing with the cognitive functions, its aim being to render accessible the ideas put forward during the evaluation and to render meaningful the different activities proposed to the trainee. The program is carried out through weekly 90-minute “stimulation” sessions. Each week, several major themes are taken up: human anatomy, memory, attention, the executive functions, mental flexibility, language, logic and reasoning. Tangible support for these discussions consists in the information sheets drawn up by the neuropsychologist and the occupational therapist ( Fig. 2 ). During the second and final part of the session, the lessons derived from the first part are systematically put into practice either through parlor games calling upon memory, attention, self-control, mental flexibility or language, or through more conventional psycho-technical drills and exercises enlivened by the emulation characterizing the functioning of a group.

This “psycho-educational” activity allows trainees to distance themselves from the initial traumatism, to become more precisely aware of their disabilities and of situations in which they are likely to fail, and to gradually internalize their retraining objectives. These sessions are particularly appreciated insofar as they reinforce the therapeutic community by creating and maintaining a culture of trust and stimulation that avoids projecting difficulties directly onto the trainee and helps to enhance his self-esteem.

1.3.2.2

Behavioral retraining and psycho-social rehabilitation

Two other forms of group management are designed to promote social rehabilitation. Each week, trainees are made to alternate between a “communication” group and a “speaking-out” group.

It should be mentioned that each group session is doubly evaluated, once by the moderator and once by the trainees themselves. At the end of each session, they open up their record booklets and fill out a self-evaluation form in which they note their interest in the theme, their participation in the discussion and their behavior as part of the group. As for the staff members, they share their observations during a weekly “wrap-up” meeting. Comparison between the trainee’s assessment and the staff’s assessment sheds light not only on potential cognitive or behavioral difficulties, but also on the degree of awareness of their existence. These different points are dealt with in more depth during individual sessions.

1.3.2.2.1

The “communication group”

The “communication group” offers an opportunity to work on verbal and non-verbal communication rules, language pragmatics, empathy ability and the “function” of theory of mind. Group dynamics are first created through the formal tasks given by the neuropsychologist such as defining emotions, interpreting gazes, engaging in role-play… After that, the trainees dialogue with each other on experiences of theirs to which the ideas they have just exchanged apply, and also on possible attitudes to adopt in given situations. According to the group dynamics, the exchanges may be more fully elaborated through informal work on short sketches or the staging of a brief play; job interviews may likewise be simulated. Little by little, the groups turn into scenes of behavioral remediation as the different simulations compel the trainee to tackle his issues with regard to conceptualization, mental flexibility, inhibition, judgment and interpretation. Interaction with fellow trainees and productive exchanges provide him with both positive reinforcement and a feedback mechanism.

1.3.2.2.2

The “speaking-out”

The “speaking-out” group offers a more open communication framework and a form of social interaction even closer to real-life situations. Trainees are encouraged to freely debate on a subject that they have preliminarily chosen themselves, while taking into account the usual social rules pertaining to communication and behavior. The staff member acting as a mediator intervenes only when it appears necessary to “fine tune” the group dynamics. The themes selected by the trainees have been wide-ranging: youth, ecology, sport, fashion, silence… This group presents an accurate translation of development with regard to language, behavior and reasoning, and it also attests to the trainees’ abilities to adapt and successfully integrate social life.

1.3.2.2.3

The social skills

Individual retraining employs a tool borrowed from psychiatry known as the Program of Reinforcing Autonomy and Social Capacities (PRACS) and focused on four areas:

- •

money management;

- •

time management;

- •

developing communication skills and leisure-time activities;

- •

learning how best to introduce oneself.

In accordance with needs, games and exercises may be organized.

Too often neglected by trainees after their traumatism, the renewal of leisure-time activities is from our standpoint an important aspect of social reintegration.

Our scheduling systematically includes an hour and a half of sport a week. The session comprises relaxation time, which is presented as a means of loosening up and a behavior regulation technique. The previously mentioned sport skills evaluation ( 1.3.1.3 ) is used individually as feedback with regard to work on representations of the body, perceptions of movement and coordination, the setting up of strategies, and behavioral adaptation. In addition, the pursuit of physical activity subsequent to the UEROS program constitutes a springboard to social reintegration.

Physical activity also facilitates ongoing reinvestment of the body, which is furthered through individual sessions, particularly “aqua-fitness” lessons in a therapeutic pool. This physical attempt at reinforcing self-esteem will soon be widened to the “socio-esthetic” workshops we are presently setting up.

Finally, the UEROS structure affords access to artistic activities in which trainees participate on a volunteer basis. Workshops in drawing, painting and modeling initiate them to different means of expression, thereby developing their creativity and enabling them to gain self-confidence. Moreover, they are regularly invited to take part in cultural outings, which allow them to discover artisanship and the performing arts.

1.3.2.2.4

The psychological approach

The network’s clinical psychologist is only intermittently present, and her task consists in providing a view from the outside when institutional difficulties arise either between trainees or between trainees and staff members. She also receives trainees who are either severely distressed or who have requested an appointment. When more structured individual management is deemed necessary, the trainee is steered towards the outpatient consultation route. This type of personalized approach is likely to extend his long-term involvement into the period subsequent to the UEROS program.

1.3.2.3

Autonomy reinforcement

The holistic management conceptions put into practice at the Limoges UEROS involve all aspects of autonomy in daily life. While the front-line professionals are the occupational therapists, social workers and family finance counselors also assume key roles. We insist on comprehensive retraining as regards hygiene, daily management tasks and mastering a budget. Work is carried out either individually or in groups.

The social and family finance counselor coaches groups taking up themes as varied as food, addictions, contraception, budgets and insurance. The trainees benefit from written support in the form of documents compiled by the departmental health education committee or the French syndical family confederation.

As for the occupational therapists, their efforts are centered on trainee autonomy from a vocational standpoint. Computer use and automobile driving are two basic skills that greatly matter when following through on a professional project. As concerns driving, we offer assistance with the administrative formalities, and when it is necessary to relearn the highway code and undertake a road test, we work hand in hand with our driving school partners, all of whom are particularly sensitized to the difficulties stemming from brain injury. A driving simulator has recently been added to these different forms of organization.

1.3.2.4

The vocational reintegration

1.3.2.4.1

The vocational project definition

Building of the trainee’s vocational project is based upon the “portrait” elaborated during his evaluation and supplemented by what he will have learned during his training period. The final project is a realistic one, structured on both the wishes of the injured person and the means at his disposal.

1.3.2.4.2

The vocational retraining

Repeated simulations of professional scenes placing the injured person in a real-life setting will allow him to “fine tune” his professional project. They can be staged with regard to all kinds of work in an ordinary or in a controlled environment. If at all possible, several work placements in different establishments should be envisioned. Their duration may vary, but they will generally last at least two weeks, and be renewable. The work pace is modulated according to the trainee’s disabilities, and will only gradually pick up. On-site weekly follow-up is provided by the staff. At the end of the vocational trial, a group interview brings together the staff, the trainee and the company, and is designed to evaluate the trainee’s behavior and his social and professional skills in such a way as to answer the question: “If a position were available, would he be hired?”

In accordance with the project, retraining also involves apprenticeship to the strategies deployed by a job seeker; this phase is undertaken in close coordination with the French employment agency called Pôle Emploi and involves participation in workshops along with the creation of dedicated “job space” on the Internet site.

1.3.3

Follow-up

Statutorily mandatory 2-year follow-up consists in an interview with the supervisor and administration of a questionnaire on the subject’s socio-professional status. The supervisor also ensures more comprehensive follow-up consisting in regular telephone conversations and meetings on request.

As regards vocational follow-up, wherever the trainee works, the occupational therapist and the occupational psychologist strive as would “job coaches” to sensitize and educate the employer and, if possible, the colleagues of the injured person. In addition, the regularly ensured interventions of our team forestall tensions and conflicts at the trainee’s workplace with regard to his condition. Problems entailed by his cognitive or motor difficulties are dealt with by modifying his tasks, while behavior disorders entail direct remediation. After the work placement has been completed, follow-up may be pursued with the Limousin brain injury patient network. As for job-seeking subjects, they are monitored in close conjunction with Pôle Emploi.

As regards social follow-up, interventions similar to those already mentioned are conducted in trainees’ families or on-site (voluntary, associative, sports activities…) in accordance with the orientations and recommendations put forward in the evaluation put together at the end of the training program.

1.4

French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units activity and results in a few figures

In order to sum up our activity and results in terms of reintegration, we have examined the files of all UEROS trainees from January 2005 through December 2008, that is to say 149 patients, and noted their development in the immediate aftermath of their UEROS training programs and as of September 2009 (at a distance of 9 to 51 months). Between 2005 and 2008, UEROS welcomed an average of 37 trainees a year (min. 35, max. 39).

Vocational reintegration is a primary objective of the Limoges UEROS; in 95.3% of all cases, the project recommended by the latter at the end of the evaluation phase involved vocational orientation. Between 2005 and 2008, no care-based orientation was recommended, and no UEROS program was interrupted on account of an inappropriate indication. The fact that only 2.7% of the patients were reoriented attests to successful recruitment and efficient coordination; moreover, 57.4 of the trainees also benefited from social reintegration.

In order to compare trainee outcome at discharge and on a long-term basis, it would appear particularly representative to enumerate the results for the 39 trainees admitted to Limoges UEROS in 2005. When discharged, 48.25% were employed (7.4% with the work placement employer, 23% with an employer catering to the special needs population, and 17.9% with ordinary employment), 17.9% were undergoing vocational training, and 33.3% were looking for work. In September 2009, 51 months later, 46.1% still had a job (28.2% with ordinary employment, 17.9% with an employer catering to the special needs population, 7.7% worked with an association, 12.8% were unemployed, 10.2% were undergoing various kinds of vocational training), 5.1% had been reoriented towards independent means of living, 5.1% had rejoined a medical assistance program and 12.8% had been lost track of.

The aim of this study was not to evaluate but rather to describe the Limoges rehabilitation program, and the results have been indicated for informative purposes alone. Compiled retrospectively and with no predefined methodology, they cannot be usefully compared to data from the literature.

1.5

Discussion

1.5.1

The role of evidence-based medicine in the Limoges French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units programs

1.5.1.1

The priority given to ecological tasks

Numerous executive function-training techniques are put into practice day in and day out by means of the ecological tasks favored by the staff. For example, in their technical workshops our occupational therapists apply problem resolution tenets, time pressure management as proposed by Fasotti , and the goal management training described by Robertson . On the other hand, task performance prediction and Luria’s verbal mediation strategy are only rarely used.

As regards culinary therapy, it is applied in a less formalized manner than with Chevignard et al. . Its goal consists not only in improved cognitive functioning, but also in experiencing the pleasure of sharing the fruits of one’s efforts in a meal partaken in common.

Our retraining program frequently resorts to games and entertainment as integral components of a rehabilitation strategy. The few available studies on game-like formats in cognitive retraining have generally reported positive results. Such formats may alleviate the stress inherent to evaluation settings while usefully resorting to varied strategies of exploration, imitation and repetition.

1.5.1.2

The uses of targeted behavioral remediation

The feedback principle is widely employed in our UEROS center through individual sessions, group therapy and videotape. The interest of feedback in therapeutic guidance has been repeatedly shown in the literature . The feedback we strive to encourage is direct, respectful, empathetic and meaningful for the person(s) involved.

In addition, metacognition and self-control are reinforced in accordance with the principle known as “self-monitoring training” , in which the trainee is systematically asked to comment on his behavior and to compare his observations to the team members’ evaluations. In the end, his judgment is enhanced and he is able to anticipate and to adjust his reactions.

Group therapy has already been shown to improve social communication skills in brain-injured persons . In our experience, regularly scheduled sessions, particularly in the “communication” and “speaking-out” groups, facilitate procedural behavioral retraining through observance and context-based reiteration of the social rules conducive to communication. According to Sohlberg et al. , behavior may improve without alteration of self-awareness, and some persons are able to learn compensatory strategies through recourse to implicit and procedural memories without necessarily apprising themselves of the interest of these strategies.

Finally, there is evidence that a combination of group-based and person-to-person interventions is likely to durably enhance performances, behavior and psycho-social well-being .

1.5.1.3

The preponderance of education

As has been reported by Ownsworth et al. , psycho-education in a group setting brings about significant improvement in self-awareness and psycho-social functioning, years after the brain injury.

1.5.1.4

The fostering of trainee awareness

Self-awareness is a highly complex phenomenon encompassing neuro-cognitive and psychological factors along with the influence exerted by the socio-cultural environment. The interventions carried out in our UEROS center represent attempts to put into practice the biopsycho-social (BPS) model of Fleming and Ownsworth by targeting the different areas in which metacognition plays a role.

Improved self-awareness is a key element in successful rehabilitation and a predictive factor with regard to employability . Prigatano has observed that the most successful subjects in his reintegration program are those who evaluate the consequences of their brain injury as does the rehabilitation team, while the subjects who fail are those whose evaluations of the consequences of their brain injury are underestimations in comparison with those of the rehabilitation team.

In the Limoges center, work on self-awareness is initiated during the preliminary evaluation and structured when the trainee’s portrait is drawn up and his efforts at self-evaluation are recorded in the diary-like training booklet.

1.5.1.5

The psychotherapeutic approach

Psychotherapy after brain injury is composed of a wide range of practices based on a number of techniques designed to improve self-awareness and foster self-acceptance through a realistic perspective on the many difficulties experienced subsequent to brain injury. According to Klonoff , on the one hand holistic management is integrally constitutive of one of these techniques, and on the other hand psychotherapy for the brain-injured employs neurophysiological tools aimed at enhancing both disability awareness and communication pragmatics. Cross-fertilization involving psychotherapy and neuropsychology is a major characteristic of management for the brain-injured .

Ever since its creation in 1978, one of the original features of the Limousin network has consisted in its being rooted in a psychodynamics-based psychiatric culture closely associating brain and psyche . With this in mind, its teams have gradually been sensitized to a double reference applying the breakthroughs achieved by the pioneers of holistic management and taking into account the emotional vicissitudes and the coping strategies characterizing the traumatic adventure.

Staff members are uniformly receptive to the psychological facts; along with the holistic dimension characterizing our establishment, their sensibility explains why our psychotherapeutic management is not isolated, but rather tends to permeate the comprehensive program we have to offer.

1.5.2

Comparison with other models of holistic management

1.5.2.1

In keeping with the precepts of American models

The holistic management carried out in the Limoges UEROS corresponds to the criteria put forward at the 1994 American consensus conference : multidisciplinary team, program contents encompassing cognitive functions, psychological factors and the socio-environmental context, rehabilitation partially undertaken in a therapeutic community, development of a therapeutic alliance between team and patient, approaches adapted to the life experience of the brain-injured person, and involvement of his family.

The group dynamics practiced in our UEROS center follow the blueprint of the milieu-oriented rehabilitation programs elaborated by Ben Yishai and Prigatano . Since the trainees feel accepted in a peer-based or therapeutic community, their interactions constitute a source of reassurance, stimulation and mutual assistance.

Contrarily to the aforementioned programs, family involvement is practiced not on a daily basis within the walls of our UEROS structure, but only occasionally, at key junctures in the patient’s development such as the decision on his admission to the UEROS, feedback from the evaluation phase, and definition of his professional project.

1.5.2.2

Some comparison with the other French evaluation, retraining, social and vocational orientation units facilities

Due to the lack of precise data pertaining to the other French UEROS centers, it is difficult to draw direct comparisons. While the list of retraining centers compiled by the different UEROS establishments includes workshops similar to those existing in Limoges, especially as regards the notion of a stimulation group and workshops encouraging free expression, the psycho-education feature is relatively absent.

In France, the first team to have rigorously applied the principles of holistic management was that of Mulhouse, and it initially did so through two programs, Delta (social reintegration) and Omega (vocational reintegration), and then through the first French UEROS establishment, which opened its doors in 1997. Today’s UEROS programs in Limoges and Mulhouse have in common their approach to group management in terms not only of cognitive retraining, but also in the framework of behavioral rehabilitation and a psychotherapeutic approach. At both centers, accompaniment takes on the form of guidance as well as regularly scheduled meetings involving the team, the trainee and his family. On the other hand, post-reintegration follow-up in Mulhouse is more systematic if not standardized, featuring a phone conversation with the supervisor at least once a week, and subsequently once a month.

1.6

Limitations

This descriptive study has been a presentation of the functioning of the Limoges UEROS and its distinct characteristics. Along with standardized tools, we have also used the internal tools we have developed on our own, and of which the validation will necessitate supplementary studies. In addition, a prospective study allowing for more precise evaluation of our trainees’ development and outcomes remains necessary.

Perspectives for development involve opening our facilities to a wider public of brain injury patients, especially those recovering from a stroke, and children, as well.

1.7

Conclusion

The Limoges UEROS offers a holistic rehabilitation program built around the trainee’s life project and recommended with regard to management of moderate to severe brain injury . The strategies elaborated in accordance with actual experience correspond to models that are clearly established in the literature. A psychological and functional approach is aimed at enhanced self-acceptance by the brain-injured patient in the perspective of long-lasting social and vocational reintegration.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree