NAIL ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND FUNCTION

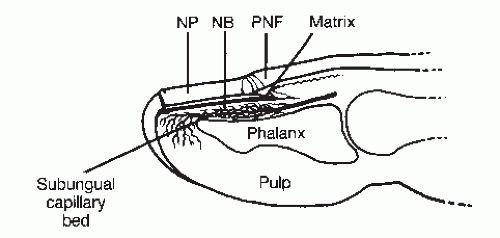

The perionychium consists of the paronychium (proximal nail fold, medial and lateral nail grooves), the nail matrix, and the nail bed (

Fig. 99.1) (

3). The proximal end of the nail plate rests in the proximal nail groove, with the proximal nail fold situated dorsally. The stratum corneum of the proximal nail fold forms the cuticle, which adheres to the dorsal surface of the nail plate. The nail plate consists of specialized keratin formed from germinative matrix cells located deep to the proximal nail fold and extending distally to the level corresponding to the distal margin of the lunula. The lunula is the visibly whitish-appearing semilunar area of matrix extending distal to the proximal nail fold and cuticle. The nail bed consists of epithelial cells that do not add to the ventral (plantar) surface of the nail plate but form a relatively smooth, longitudinally furrowed plateau on which the nail plate glides as it grows distally (

4,

5). It takes at least 5 to 6 months, and frequently as long as 9 months, to grow an entirely new toenail in a healthy adult. In general, toenails grow faster in children as compared with adults, and fingernails grow faster than do toenails. Moreover, toenails tend to grow faster in warmer environments and wellperfused digits.

The subcutaneous region deep to the nail bed is highly vascularized, and the nail bed and matrix are situated almost immediately adjacent to the periosteum of the distal phalanx. In essence, the nail bed anchors the nail plate to the distal phalanx, and at least 5 mm of healthy nail bed distal to the lunula is generally necessary for satisfactory nail plate adherence and stability (

6). This is an important guideline for reconstruction of digital-tip injuries that involve loss of the distal portion of the nail bed.

The plantar toe pulp consists primarily of subcutaneous tissue providing a firm, yet elastic pad for contact with the weightbearing surface. Afferent nerves terminating in the toe conduct touch-pressure and temperature sensations, allowing proprioception and nocioception, whereas digital vascular structures (subungual glomus) permit effective peripheral temperature regulation. The resilient nail plate protects these underlying structures from injury and combines with the distal phalanx to provide a stable support against ground reactive force as the toe pulp contacts the substrate.

Nail matrix and bed damage can result in poor nail plate adherence and malalignment. Onycholysis, onychocryptosis, and a predisposition to onychomycosis, or bacterial infection, may develop following injury. Hypertrophic, dystrophic, and deformed nails with ridges, split-nail (canaliformis) changes, discoloration including streaking and loss of normal nail plate sheen, and pterygium formation (permanent adherence of the proximal nail fold ventral epithelium to the dorsal surface of the nail plate) may occur after perionychial injuries. It has been reported that distal growth of the nail plate is arrested or delayed for up to 21 days following local trauma or significant systemic stress to the individual (

7). This results in the appearance of relative thickening of the nail plate proximal and distal to the visibly thinner transverse line of diminished nail plate production. Proximally, the newly formed nail plate is actually thicker than the normally formed, distal segment of the plate. The proximal thickening results from an approximately 50-day period of increased matrix activity without distal elongation of the plate. Toward the end (last 30 days) of the period of increased matrix activity, distal progression of the nail plate occurs. Following the period of increased nail plate production, there is an approximately 30-day period of decreased activity before normal matrix activity resumes. Therefore, approximately 100 days of abnormal nail plate production can be expected following trauma. The nail plate will typically reveal a transverse groove, or Beau’s line, after such an injury (

Fig. 99.2). Other late term sequelae to injury of the nail root include ectopic nail formation (onychoheterotopia), which is a rather rare occurrence wherein nail-like growth develops in an area separate from the normal nail bed (

8), as well as contraction of the soft tissues of the proximal nail fold, proximal to the nail plate and exclusive of the nail matrix and bed, which is commonly associated with digital burn wounds (

9).

The nail plate and perionychium are subject to a variety of injuries ranging from minor contusions to trauma causing severe tissue loss and the need for either acute or delayed surgical reconstruction. The hierarchy of nail bed injuries, ranging from least extensive to most extensive, includes primary

(idiopathic) onycholysis, subungual hematoma, simple nail bed lacerations, complex (crushing or stellate) nail bed lacerations, nail bed lacerations with distal phalangeal fracture, and a variety of nail bed and toe-tip tissue loss (avulsion, amputation, and degloving) injuries (

Table 99.1). A more comprehensive system of digital-tip injuries has been described in regard to repair of fingertip trauma and is known as the pulp-nail-bone (PNB) classification (

10) (

Table 99.2). The PNB classification has gained popularity among hand surgeons due to its descriptive capabilities and ease of communicating the precise location and characteristics of the full range of digital-tip injuries (

11). Patients with such injuries may seek medical attention at the hospital emergency department or the local foot surgeon’s office. Accurate initial diagnosis of the extent of injury and proper initial treatment will greatly enhance the chance that posttraumatic sequelae will be minimized (

12). A useful guideline to remember for the acute care of the traumatized nail is to preserve the unity of the toe tip: nail plate, nail bed and matrix, proximal and medial and lateral nail folds, distal phalanx, and the toe pulp.

MECHANICAL ONYCHOLYSIS

Mechanical onycholysis, or minor separation of the nail plate from the underlying bed due to repetitive friction and pressure, is not, in any way, considered an emergency situation. However, a distinction between chronic mechanical nail injury and pathogenic onychomycosis should be made so that appropriate therapy can be rendered (

13). Separation of the nail plate from the underlying nail bed effects a change in the nail plate’s refractive index to light, and the area of separation appears as a small white blotch in the nail plate. Mechanically induced separation of the distal margin or edges of the nail plate from the nail bed often occurs in conjunction with hammertoes and other digital contractures, or digital pressure caused by tight-fitting shoes, and frequently affects the hallux or longest toe. The area of nail plate separation may become secondarily infected with dermatophytes, yeast, or bacteria. Associated subungual hematoma may also occur, especially in athletes (turf toe). Treatment is aimed at alleviating the cause of the repetitive mechanical trauma and providing appropriate antimicrobial therapy, if necessary.

SUBUNGUAL HEMATOMA

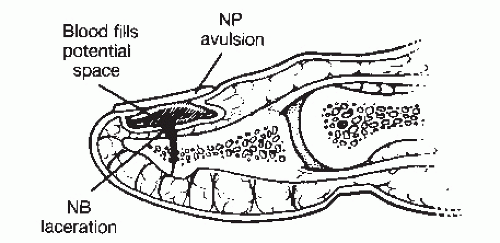

A potential space exists between the nail plate and the underlying nail bed and matrix (

Fig. 99.3). Onycholysis results in the creation of a space between the plate and bed, which may or may not fill with blood. Acute injuries that create visible onycholysis greater than 1 mm

2 usually result in subungual hematoma. When a patient is seen with a swollen toe and reports throbbing pain shortly after sustaining a digital injury, nail bed damage and subungual hematoma should be suspected. Subungual pressure secondary to hemorrhage can damage cells of the matrix and nail bed, especially if it is not relieved within 6 to 12 hours after the initial trauma. Hemorrhagic nail plate discoloration, which appears reddish blue initially and brownish black after 5 to 7 days, confirms the diagnosis of a disrupted nail bed. Unless subungual hematoma is suspected, it may be overlooked in the presence of a thick, discolored, or mycotic nail plate because the overlying dystrophic nail plate can hide the hematoma. Moreover, radiographs of the digit should be considered during the initial evaluation of a subungual hematoma because approximately 19% to 25% of these lesions are associated with an underlying phalangeal fracture (

2,

14).

Treatment of subungual hematoma involves draining the blood to reduce subungual pressure. If the hematoma involves an area less than 25% of the visible nail plate, drainage can be obtained through the nail plate with the use of a hand cautery unit, an 18-gauge needle, a no. 11 blade scalpel, a heated paper clip, or a rotary drill with an appropriate small ball bur or bit (

3,

14). The status of the patient’s tetanus prophylaxis should be ascertained and the nail plate cleansed before penetrating it. Consideration should also be given to the use of appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis or therapy, when indicated.

Unfortunately, trephination of the nail plate in an effort to drain subungual hematoma in the presence of intact nail folds can be painful, especially if the nail bed is subjected to contact with the cutting instrument used to bore through the nail plate. For this reason, a number of options have been used to enable satisfactory evacuation of the hematoma without inflicting pain. Obviously, proximal nerve blockade with local anesthetic can be used to completely eliminate pain related to distal manipulation of the injured nail plate and bed; however, administration of the local anesthetic block can be painful in and of itself. Moreover, it can be difficult to apply enough pressure to the trephine, bur, or other cutting edge, or heated coil, to readily penetrate the nail plate without contacting the nail bed. In an effort to avoid pain associated with contact with the nail bed after penetrating the nail plate, the use of a motorized device (PathFormer, Path Scientific, Carlisle, MA) to drill completely through the nail plate while lowering the cutting edge has been recommended (

15,

16). The device is adjusted to stop drilling and penetrating based on the selected amount of electrical resistance (kiloOhms). Since the water content of the nail bed is much higher than that of the nail plate, the electrical resistance of the nail plate, which approximates 5 mΩ, is much greater than that of the nail bed, which is 10 to 20 kΩ. The motors that lower and rotate the drill bit through the nail plate are linked to the bit by means of an electrode that registers the resistance of the tissues at the tip and, as soon as a resistance of 10 to 20 kΩ is registered, the motors stop and the device is removed. In this way, subungual hematoma can be evacuated without excessive contact with the sensitive nail bed and without the need for local anesthetic blockade of the injured toe. To our knowledge, this device has not yet come into widespread use, and we have not yet personally used it ourselves.

Once the plate is penetrated, blood is expressed and subungual pressure alleviated. A water-soluble antiseptic solution or antibiotic cream and a dry sterile dressing with appropriate splinting are then applied, and the patient is reevaluated in 1 to 2 weeks. If the subungual hematoma involves more than 25% of the visible nail plate or the nail plate has been avulsed in such a way as to disrupt the proximal, medial, or lateral nail folds, then a significant nail bed laceration should be suspected and direct visualization and surgical repair of the nail bed is recommended (

Fig. 99.4) (

3,

17). Although repair of the lacerated or avulsed nail bed remains the most common approach to such injuries, it is not the only way to manage these cases. In fact, in a prospective study of 52 children, Roser and Gellman (

18) compared fingernail bed repair with simple trephination and no surgical intervention for fingernail injuries that resulted in subungual hematoma occupying greater than 25% of the nail bed. In that study, the authors reported no significant difference in outcome between the treatment groups. It is also interesting to note that in one series of 12 cases, observed over an approximately 7-year period, severe avulsion injuries were treated successfully without grafting the injured nail bed (

19). Furthermore, in another series, 66 patients with nail bed lacerations were treated only by means of drainage of the hematoma, cleansing débridement, and replacement of the nail plate with an overlying tension suture (

20).