Nightingale who is noted to have started the profession of nursing, and continuing up to current day conflicts, military nurses have provided frontline injury care. In an early publication on the role of trauma nursing, Beachley notes that military nurses established the first principles for nursing management of devastating traumatic injuries: triage, rapid evacuation, surgical intervention, stabilization, and early rehabilitation.1,2 As early as the 1800s, there is documentation of the role of trauma nursing in the United States. This was initiated when General George Washington requested at the start of the Revolutionary War that the Second Continental Congress provide for the establishment of “female nurses to attend to the sick.”2,3 In 1901, the Army Nurse Corps was permanently established and at this time it was restricted to women. In 1904 by an Act of Congress, the American Red Cross was reorganized with a provision for a flexible nursing reserve, with chapters in all states who could be mobilized in times of national emergency.3,4 In 1908, the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps was established. By the end of World War I, their numbers had increased to 1,286. A total of 2,000 regular Army nurses and 10,186 reserve nurses were on active duty at 198 stations worldwide by June 1918. In World War II, more than 50,000 nurses served in the Army Nurse Corps. There were 200 military nurses killed by hostile fire during World War II and at least three Army nurses were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest military honor. In 1943, the first class of Army Nurses Corps flight nurses graduated from the School of Air Evacuation at Bowman Field, Kentucky and the Air Force Nurse Corps was established in 1949. Captain Lillian Kinkela Keil, a member of the Air Force Nurse Corps, flew more than 200 air evacuation missions during World War II as well as 25 transatlantic crossings. She returned to service during the Korean conflict and flew several hundred more missions as a flight nurse in Korea.4,5 Important lessons learned from the nurses who were caring for injured patients at altitude, with unique environmental considerations like vibration and noise, helped inform the process of developing civilian air medical transport teams. Models utilizing flight nurses to support civilian health care systems developed successfully from the military model.6 In his report titled the

Department of the Army’s Vietnam Studies, Medical Support 1965-1970, Major General Spurgeon H. Neel noted that the Vietnam War witnessed an evolution in trauma and combat casualty care. Progress in medical evacuation advanced the concept of intensive care nursing as a standard approach. This was followed by trauma care specialization and the eventual development of shock/trauma units. Rapid aerial evacuation, rapidly available whole blood, well-established forward hospitals, advanced surgical techniques, and improved medical/nursing management contributed to the prevention of deaths from battle wounds. The hospital mortality rate during the Vietnam War was 2.6% per 1,000 patients compared to 4.5% during World War II.6

TABLE 1 KEY MILESTONES OF THE SOCIETY OF TRAUMA NURSESa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 2 KEY ADVANCES IN CARE OF CRITICALLY INJURED IN COMBAT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

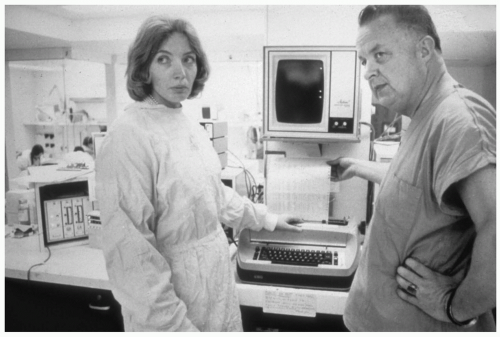

early trauma centers at Shock Trauma in Baltimore and Cook County in Chicago were in inner city/urban environments. There were not yet sophisticated diagnostics or blood transfusion, so the development of patient care plans relied primarily on the physical examination and ongoing assessments/monitoring. Military nurses helped to promote the practice of team nursing exemplifying the “can do” attitude. (R.N. Elizabeth Scanlan, personal communications, 2007.)

at Cook County opened. In this model, injured patients coming to Cook County bypassed the ED and went straight to a specialty trauma/resuscitation unit. In 1970, the Illinois legislature funded development of a trauma system. In 1971, Terry Romano, RN was hired as the first trauma nurse coordinator to direct education for nurses working in the developing Illinois trauma system. Dr. David Boyd and Terry Romano, RN together played a critical role in developing trauma care systems in the United States. Using medical corpsmen in a civilian setting, Dr. Boyd deployed these personnel, paired with nurses, to the hospitals that were going to be designated in the newly developing Illinois trauma system. Romano developed a Trauma Nurse Specialist (TNS) Course and based the curriculum on concepts that Norma Shoemaker had implemented in nursing practice at Cook County. (R.N. Teresa Romano, personal communications, 2007.) This curriculum was published in the American Journal of Nursing in 1973 and is one of the earliest articles outlining the role of the trauma nurse.

Figure 1 Elizabeth Scanlan, RN and R Adams Cowley, MD—Baltimore Shock Trauma Center, Maryland—1970s. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree