31 TRAUMA IN THE BARIATRIC PATIENT

Bariatric trauma patients present many challenges for health care professionals from the time of injury through rehabilitation. Principal challenges associated with problematic outcomes in critically injured bariatric trauma patients include obtaining a comprehensive assessment, meeting the patient’s physiologic requirements, and providing effective interventions. Providing health care to this special population lends specific risks and needs that must be recognized early and maintained throughout the continuum of care. Preparation should begin early, before arrival if possible, to accommodate the unique needs of the bariatric trauma patient. It is essential that nurses caring for bariatric trauma patients have an understanding of the anatomic differences, special equipment requirements, and psychologic needs of bariatric patients. Despite the recent increase in research related to the needs and injuries of the bariatric trauma patient, many nurses remain ill prepared to provide the specialized care required for this patient population.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

One only needs to pick up a magazine or watch the news to be reminded that obesity is at epidemic levels among the general population. The statistics of obesity in the United States are staggering. After the millennium, more than one half of all Americans are overweight, more than 30% are obese, and greater than 5% are morbidly obese.1,2 Obesity results in greater than 100,000 deaths each year in the United States, making it the leading cause of preventable death with an annual estimated cost of $70 to $100 billion.2,3

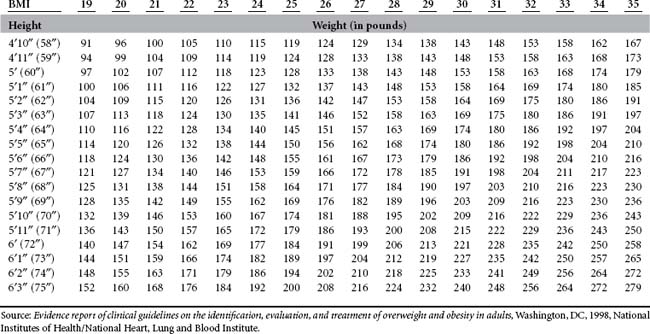

Obesity is defined as an abnormal increase in weight compared with the age, sex, height, and body type of an individual.4 Bariatric patients include those persons who are overweight, obese, and morbidly obese and those who have had some form of weight loss surgery. The body mass index (BMI) is the standard method used to evaluate obesity. Degrees of excess weight are frequently classified with the BMI, which correlates weight and height.5 BMI is determined according to the following formula: BMI = weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (Weight [kg])/Height [m2]).6 Table 31-1 summarizes the classifications of adult obesity according to the BMI.1,5,6 Table 31-2 illustrates the correlation of BMI to height and weight for adults.

TABLE 31-1 Classifications of Obesity in Adults

| Weight Classification | World Health Organization Classification | BMI |

|---|---|---|

| Normal weight | Normal weight | 18.5-24.9 |

| Overweight | Overweight | 25.0-29.9 |

| Obese | Grade 2 overweight | 30.0-39.9 |

| Morbidly/severely obese | Grade 3 overweight | 40.0-49.9 |

| Super obese | Not applicable | >50.0 |

Obesity is not a problem that is unique to adults. Each year the number of obese children in the United States continues to increase. Obesity in children is defined according to how their weight compares with the national percentile for both their age and sex. Standard growth charts are used to determine what percentile children and adolescents fall in for both height and weight.5 Although children whose weight is between the 85th and 95th percentiles are termed overweight, those whose weight falls in the range greater than the 95th percentile are classified as obese.3 These statistics indicate that one in five children in the United States falls into either the overweight or obese category.6

Although the number of articles being published in professional journals regarding the care of bariatric trauma patients is increasing, a major deficit in both research and literature persists. Trauma has been identified as the fifth leading cause of death in adults and the most common cause of death in children in the United States.7,8 Trauma patients who are obese, with a BMI greater than 30, and those who are morbidly obese, with a BMI of 40 or higher, have been shown to have a significantly greater number of complications, longer time on a mechanical ventilator, and higher mortality rates compared to individuals with similar injuries who are normal weight with a BMI less than 25.9–11 Morbidly obese trauma patients are eight times more likely to die from their injuries than are those with a normal BMI (<25 kg/m2).7

Studies probing for a correlation between obesity and mortality rates in trauma patients have various outcomes. A retrospective study by Morris et al12 attempted to correlate preexisting medical conditions with negative outcomes for trauma patients. In this study obesity was not found to be a significant factor. The results of the Morris et al study may have been skewed by a failure to include obesity as a secondary diagnosis. Another retrospective study published a year later by Smith-Choban et al13 found a significant correlation between the mortality rate of trauma patients and obesity. More recent studies by Arbabi et al,9 Brown et al,10 Byrnes et al,11 and Neville et al14 have supported the hypothesis that obesity is an independent risk factor in the mortality rate of trauma patients. A study by Whitlock et al15 found a U-shaped correlation between BMI of drivers involved in vehicular crashes and the rate of critical traumatic injuries sustained, not including deaths. This U-shaped distribution represents a twofold increase in the injury rate for drivers in the lowest weight classification (<23.5 kg/m2) and those in the highest weight class (>28.7 kg/m2).15 The U-shaped results of this study may be attributed to an increased risk of broken bones among individuals within the low weight range, a greater risk of falling asleep as a result of sleep apnea while driving for the overweight group and possibly aspects of vehicle safety design that are less effective for those who are overweight or underweight.15 Despite the need for further research, studies with a clear definition of obesity, BMI greater than 30, and a relatively large number of patients included in the study show a significant correlation between obesity and an increased mortality rate in trauma patients. Further research needs to be done to ascertain exactly why obesity increases the risk of death for trauma patients.

NURSING DATABASE

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Blunt Trauma

A study by Brown et al10 found that patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2 who sustained injuries from severe blunt trauma typically had different patterns of injury than those with a BMI <25 kg/m2. A total of 1,153 patients were included in the Brown et al study, including 283 obese patients and 870 nonobese patients. The patients in the obese group were found to have a lower rate of head injury but a higher risk of chest and lower extremity injuries. Patients with a BMI >30 also had a higher rate of complications and death.

A 1998 study by Bazelmans et al16 found that obese adolescents who participated in sports were more likely to be injured than were their normal-weight peers. This study found no correlation between obesity and the increased severity of injury.16 Use of protective gear (i.e., helmet, wrist guards, and knee and elbow pads) should be documented, particularly for traumatic incidents involving contact sports, motorcycle riding, bicycling, rollerblading, and skateboarding. School-age children who are overweight also tend to be targeted by bullies. Schoolyard fist fights frequently result in blunt trauma to the face and torso.

Falls

A British study by Spaine and Bollen17 found a correlation between increased BMI and the severity of ankle fractures. Only patients who had ankle fractures after “low energy trauma,” such as ground level or low level falls, were included in the study. Obese patients with displaced ankle fractures were also more likely than their normal-weight counterparts to have a redislocation injury.

Motor Vehicle Crash

Potential injury patterns can be determined on the basis of knowledge of the patient location in the car, use of safety restraints (lap belt only or lap belt and shoulder harness), air bag deployment, steering wheel deformity, ejection of the patient from the vehicle, passenger space intrusion, and the condition of other people in the same automobile. A study of the injury patterns of restrained drivers by Moran et al18 found that drivers whose body type was not similar to that of the crash test dummy frequently did not fit correctly in the vehicle, making safety features less effective, ineffective, or dangerous. The typical crash test dummy is patterned after a 5 foot 10 inch male weighing 170 pounds, a BMI below that of those classified as overweight or obese.18

According to a study by Reiff et al19 there is an increased rate of diaphragmatic injuries in front seat passengers who are overweight and involved in motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) where the damage to the vehicle involves same-side passenger space intrusion. Compared with automobile passengers of normal weight, a higher risk of rib fractures and pulmonary contusions was noted in obese passengers of MVCs by Choban et al.20 Arbabi et al9 studied 189 patients who were involved in MVCs, comparing injury patterns and mortality rates for normal-weight individuals (BMI <25 kg/m2) versus obese individuals (BMI >30). Although the results of this study did not find a correlation between obesity and increased Injury Severity Score, obesity was found to be associated with an increase in severity of lower extremity injuries, including pelvic fractures, and overall mortality rates. The Arbabi et al study also reported a decrease in the number of abdominal injuries among obese patients. The authors of this study suggest that the lower rate of abdominal injuries in the obese group may be associated with the “cushion effect” provided by layers of adipose tissue over the abdomen.

Burns

Obese or morbidly obese individuals who have difficulty ambulating, are unable to ambulate without assistance, or are completely nonambulatory are at greater risk of significant burn injuries and inhalation injuries when they are victims of structure fires. A 1993 study by Gottschlich et al21 found that burn patients who are obese or morbidly obese have higher risk of infection, bacteremia, and sepsis. This study also found that obese burn victims required twice as many doses of antibiotics and insulin as did nonobese burn patients. Obese burn patients also have higher metabolic demands than burn patients with a BMI <25.

Burn victims who have significant smoke inhalation injuries may require emergency airway management. Anatomic differences, such as extra layers of adipose tissue and a short neck, make intubating an obese patient difficult and often impossible. Alternatives to intubation for the obese patient include the use of a Combitube or percutaneous tracheostomy.22,23 As with other forms of trauma, obese burn victims typically necessitate longer periods of time on mechanical ventilation than do burn victims who are normal weight.21

MEDICAL HISTORY

It is important to obtain information about the medical history of all trauma patients. If the patient is not able to answer questions, then information should be obtained from a family member or friend if possible. Using the acronym AMPLE will help the trauma team to obtain a thorough patient history: A: allergies, M: medications, P: past medical history/surgeries/pregnancies, L: last meal, and E: events surrounding the injury.24 Table 31-3 has examples of pertinent information (in AMPLE format) that should be obtained when caring for a bariatric trauma patient. Medical history questions specific to bariatric patients include questions regarding medical conditions that affect mobility, diet, weight loss medications or supplements, previous weight loss surgeries, and diseases.

TABLE 31-3 Using AMPLE to Obtain a Medical History for a Bariatric Patient

| A | Allergies | Are you allergic to any medications? What type of reaction have you had after taking this medication? |

| M | Medications | What medications do you take on a routine basis? Prescription? Over the counter? Supplements? (Note any weight loss medications/supplements.) |

| P | Pertinent past medical/surgical/obstetric history | Do you have any medical history? (Specifically ask about diseases frequently associated with obesity, see Table 31-5.) Surgical history? Any form of weight loss surgery? Obstetric history: gravida, para, and abortions (spontaneous or elective). Is there any chance that you could be pregnant? Last menstral period? |

| L | Last meal | What time did you last eat or drink? What did you eat or drink? (Includes, water, protein shakes, or weight loss shakes or bars.) |

| E | Events related to the mechanism of trauma | How did the injury occur? Where did the injury occur? Do you use an assistive device to walk (e.g., cane, walker)? Do you normally stand or walk alone? |

RESUSCITATION PHASE

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT/TEAM APPROACH

When caring for bariatric patients, the term team approach has a dual meaning. As with any trauma patient, the assessment and care of the patient is a combined effort of trauma surgeons, emergency physicians, trauma nurses, and other support staff. The initial focus of the team is to perform a primary and then a secondary survey of the patient to rapidly identify and treat life-threatening injuries. (See Box 31-1 for an example of the guidelines used by one trauma center when caring for morbidly obese trauma patients.) In addition, bariatric trauma patients require more manpower to position, turn, and transport. To prevent injury to the patient or team members, it is important to ensure that enough help is present to perform these maneuvers safely.

BOX 31-1 Resuscitation of the Morbidly Obese Trauma Patient

I. OBJECTIVE: Resuscitation of the morbidly obese trauma patient can pose major difficulties in airway, breathing, and circulatory management as part of the primary survey, and then further difficulties with the secondary survey.

II. POLICY: The Guideline is designed to assist the trauma team in caring for morbidly obese trauma patients.

III. DEFINITION: A body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 or if using the Body Mass Index Table >20% over the patient’s calculated ideal body weight (IBW) (see Table 31-2).

Some extremely obese patients have undiagnosed sleep apnea and obstruct their airway when lying flat

• Breathing (assessment of breath sounds can be difficult)

Secondary assessment—special problems with the morbidly obese

• Recommendations for multisystem or moderately severe single system injury (AIS >4)

Borrowed with permission from Shands at the University of Florida.

ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF THE BARIATRIC TRAUMA PATIENT

The assessment and treatment of bariatric trauma patients may vary from other trauma patients because of differences in body composition, inability to use some forms of standard diagnostic machinery or techniques, and the need for more personnel to perform procedures. Table 31-4 provides an overview of challenges faced in the primary survey of a bariatric trauma patient.25 Obesity affects all of the major systems of the body. Special consideration needs to be given to how the differences in each system affect the care and recovery of bariatric trauma patients.

TABLE 31-4 Assessment and Management Challenges