Chapter 7

Training motor tasks

Often patients with spinal cord injury are unable to perform motor tasks because they lack skill. That is, they do not know how to move optimally with their newly acquired paralysis. For example, rolling in bed is initially difficult for a patient with high-level paraplegia. An inability to roll is rarely due to lack of upper limb strength or poor joint range of motion; more often it is due to an inability to swing the arms rapidly across the body while lifting the head.1 The task is novel and must be learnt. Some motor tasks are within themselves novel, such as performing a wheelstand.2,3 They also must be learnt.

Motor control and motor learning

The importance of training motor tasks for patients with neurological disabilities was first advocated by Carr and Shepherd as part of their ‘Motor Relearning Approach’,4–7 and later by Shumway-Cook and Woollacott in their ‘Task–Oriented Approach’ (also called the ‘Systems Approach’).8 These approaches are based on theories about motor control and motor learning and primarily developed for the physical rehabilitation of patients with stroke and brain impairments.5–7,9–14

The mechanisms underlying motor control and the acquisition of motor tasks are complex and not fully understood. A range of paradigms, each with their own theories, have been used to explain motor control and motor learning.6,8,15–18 Two key theories which have influenced neurological physiotherapy are Bernstein’s ‘motor schema theory’19 and Fitts and Posner’s three key stages of motor learning.20 These theories have primarily evolved from research with able-bodied individuals and athletes, but arguably are equally applicable to patients with spinal cord injury. They are important because they help explain how patients with spinal cord injury learn motor tasks and how physiotherapists can best facilitate the learning process.

The ‘motor schema theory’ is based on the premise that control strategies are matched to the specific context of motor tasks. There are an infinite number of contexts for the performance of motor tasks, so it is not possible to learn separate motor strategies for all the possible contexts. Instead, it is proposed that motor tasks are largely controlled by motor schemas.16–18 Motor schemas provide a background programme or code which dictates the timing, order and force of muscle contractions. They are like basic building blocks which dictate the general rules for movement. Once motor schemas are set down, motor tasks can be performed with a certain degree of automaticity.21 This enables people to perform motor tasks while concentrating on other mental or physical activities. It also explains the skilled performer’s ability to perform a motor task very rapidly when there is little time to rely on feedback mechanisms. Motor schemas can be modulated to accommodate variations in speed or the precise way motor tasks are performed. Patients with spinal cord injury are initially unable to perform novel motor tasks because they do not have the necessary motor schemas. New motor schemas are required to code how, when and in what way non-paralysed muscles need to contract for purposeful movement.

Fitts and Posner20 proposed that motor tasks are learnt in three key stages. These are:

1. Cognitive stage. During this time people attain a general understanding and ‘cognitive’ map of the overall motor task. People use trial and error to gain an approximation of the motor sequencing. Attempts at movement are associated with excessive effort and unnecessary muscle contractions. Visual feedback and other sensory cues are particularly important during this stage.

2. Associative stage. Refinement of the motor task occurs at this point. The movement is performed in a more consistent way and unnecessary movements are progressively eliminated. People are increasingly attentive to proprioceptive cues which refine how movements are performed

3. Autonomous stage. In this stage movement becomes more automated, requiring less effort and concentration. There is little error and little unnecessary associated movements. The skill can now be successfully performed in varied environments and does not require ongoing practice to maintain competency.

Principles of effective motor task training

The training of motor tasks in patients with spinal cord injury relies on physiotherapists’ problem-solving skills and their understanding of how patients with different patterns of paralysis move (see Chapters 3–6). Initially, physiotherapists need to identify the motor tasks which patients can hope to master (such as rolling, sitting unsupported, moving from lying to sitting, transferring or walking; see Chapter 2). This is formally done through the goal planning process. Patients are asked to perform these tasks and their attempts at each motor task are then analysed. The aim of the analysis is to identify which sub-tasks patients can and cannot perform, and determine the reason why patients cannot perform specific sub-tasks. The reason for failure to perform a sub-task needs to be expressed in terms of one or more impairments (usually lack of skill, strength, joint mobility or fitness). When lack of skill is the primary impairment, physiotherapists need to teach patients appropriate movement strategies. This chapter focuses on how physiotherapists can train important motor tasks which need to be learned by patients with spinal cord injury.

The importance of practice

A key feature of learning motor tasks is intense, well structured and active practice which is task- and context-specific.4–8 Task- and context-specific practice implies practise of precisely the task which needs to be learned. For example, patients with the potential to stand need to actively and intensely practise standing6 and patients with the potential to transfer need to practise transferring.

The ‘similar but simpler’ approach

The ‘similar but simpler’ approach requires breaking complex motor tasks into sub-tasks and practising each individually, if necessary in a simplified way.6 Sub-tasks are progressively made more difficult as patients master them. Sub-tasks are then practised in an appropriate sequence until the whole task is mastered.

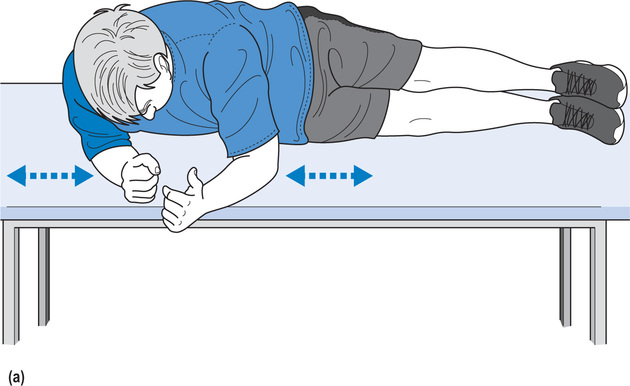

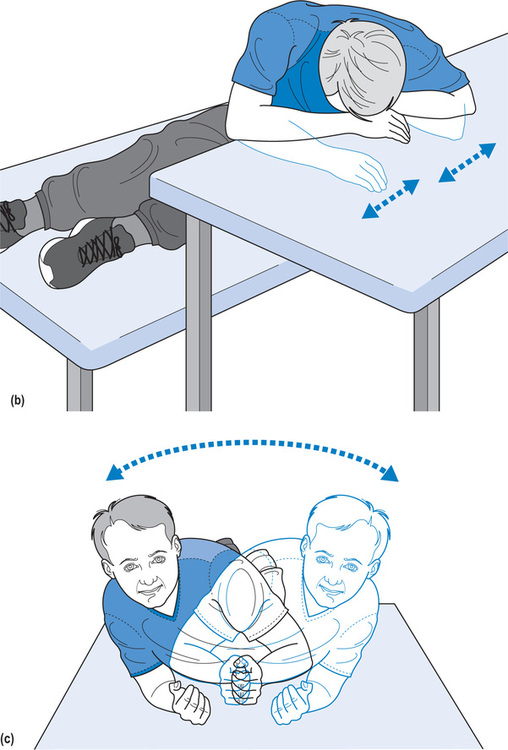

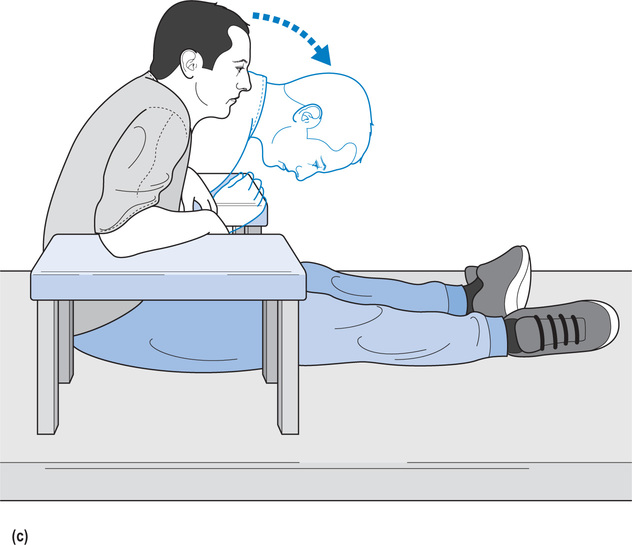

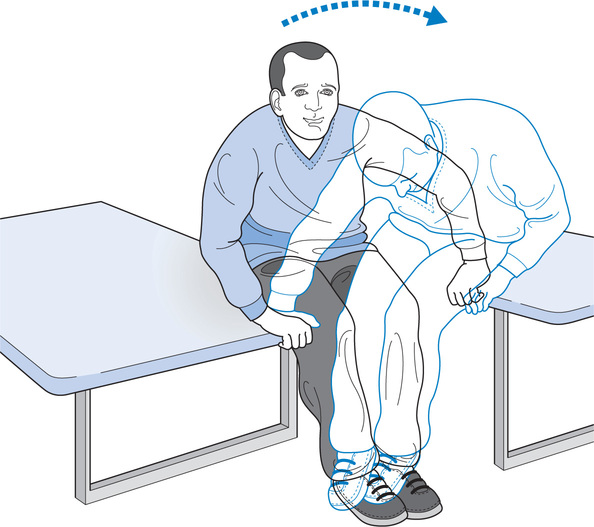

For example, a patient with C6 tetraplegia may be unable to move from lying to sitting because of an inability to bear and shift weight through the elbows in an awkward side-lying position: an essential sub-task of moving from lying to sitting (see Figure 7.1a). The patient may benefit from practising bearing and shifting weight in the same awkward position but with the elbows supported on a higher adjacent bed (see Figure 7.1b). Alternatively the patient may benefit from practising bearing and shifting weight in a prone position (see Figure 7.1c). In both instances the patient practises a motor task which is similar but simpler to the original sub-task. If patients are in the very early days of rehabilitation and unable to do either of these exercises, they might practise an even simpler variation, such as sitting in a wheelchair leaning through elbows placed on high adjacent beds (see Figure 7.2b). The height of the bed can be adjusted to increase difficulty. These exercises are directed at improving patients’ ability to bear weight through the elbows because this is an essential sub-task of moving from lying to sitting.

If the same patient was unable to transfer due to an inability to lift and shift weight forwards and laterally (see Figure 7.2a), therapy would consist of simplified drills and exercises to address this specific sub-task of transferring. For instance, the patient could practise lifting through fully extended elbows while sitting on a plinth. Small blocks could be placed under the hands if this made the task easier for the patient (see Figure 7.6). A slippery board or sheet could be placed under the legs to promote a forward slide. The patient could practise with the knees extended to minimize the likelihood of a backwards fall but then progress to lifting with the knees flexed (i.e. sitting over the edge of the plinth). Initially the patient may require trunk support but with progress this can be withdrawn. Some patients may be unable to do any of these exercises, and instead may benefit from practising something as simple as lifting body weight through flexed elbows while either sitting in a wheelchair (see Figure 7.2b) or sitting on a plinth (see Figure 7.2c).

A similar process is followed for patients with more advanced skills. For instance, a patient with thoracic paraplegia unable to perform difficult transfers in community settings might benefit from practising a similar but easier transfer between two physiotherapy plinths (see Figure 7.3). The transfer training concentrates on the particular sub-task which the patient is having difficulty with.

Experienced physiotherapists have a large repertoire of appropriate drills and exercises for all the sub-tasks comprising the various motor tasks patients need to learn. They draw on this repertoire to provide patients with varied, interesting and effective training programmes appropriate for patients’ stages of learning and rehabilitation. Examples of ways to simplify sub-tasks for training can be found throughout the tables in Chapter 3. Readers are also directed to a website developed by the author and her colleagues: www.physiotherapyexercises.com This website describes hundreds of ways to simplify motor tasks. Alternatively, with a little imagination, physiotherapists can devise their own unique training drills.

Progression

Training needs to be appropriately progressed. This is achieved by articulating goals for each therapy session (see Chapter 2). The goals may be for very modest increments in performance, but nonetheless must be clearly defined. As soon as a goal is consistently attained, a new goal is set. The new goal may be to perform the same task in a slightly different situation, at a slightly faster pace, or while performing concurrent tasks.21,22 Concurrent tasks might be physical or cognitive. For instance, gait training could progress to walking while carrying shopping bags or reciting numbers.21 Initially, the patient might practise in the fairly constrained and close environment of the physiotherapy gymnasium then progress to practising in a more complex and changing community environment with its inherent distractions. Goals should be written and their achievement recorded.

Practice outside formal therapy sessions

Complex motor tasks cannot be learnt without repetitious practice.6,23,24 Surprisingly, however, only two randomized controlled trials have looked at the effectiveness of practice and training in people with spinal cord injury. Both studies looked at the effectiveness of a wheelchair skills training programme, and demonstrated the effectiveness of structured and repetitious practice for the acquisition of wheelchair skills.25,26

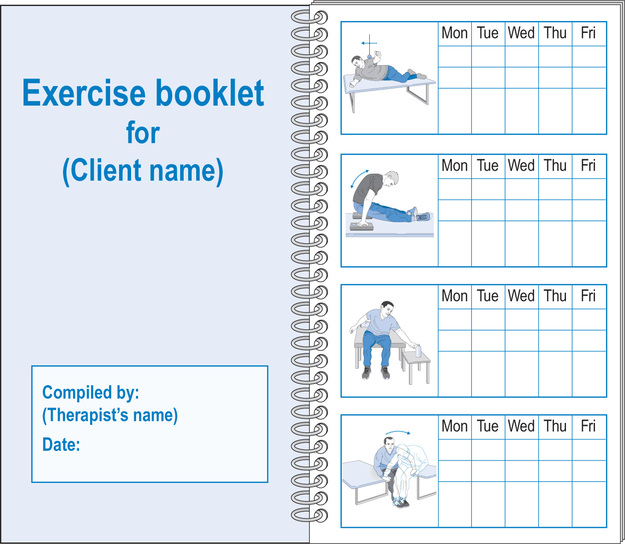

Practice needs to be performed during therapy sessions but also, wherever possible, practice should be performed in patients’ own time. Practice out of therapy time should be structured with the same care as practice in therapy time. Importantly, practice outside formal therapy needs to be monitored. For example, an ambulating patient who is asked to practise stepping outside therapy should be required to record either the number of steps or the time spent on this activity. Commercially available step counters can be used for this purpose. Physiotherapists need to review written records of practice, and provide feedback on the quantity and quality of practice to reinforce the belief that practice is important. Personalized exercise booklets provide an excellent way of structuring and monitoring practice, both within and outside formal therapy sessions (see Figure 7.4). The website at www.physiotherapyexercises.com. can be used to generate professional looking customized exercise booklets.

One of the biggest challenges in designing effective training programmes is ensuring they maintain interest and motivation. This can be achieved by providing a variety of exercises, setting clear and attainable goals, and progressing task difficulty as performance improves. A particularly useful strategy for maximizing interest and motivation is to provide group sessions in which patients of similar ability practise together.11 This also serves to reduce demands on physiotherapists’ time.

Effective training methods

Motor learning can be enhanced by effective use of instructions, demonstrations and feedback.

Instructions

Instructions need to be tailored to the stage of learning and the patients’ cognitive abilities. During the early stages of learning, instructions need to be general and targeted at the overall goal. For example, instructions appropriate for a patient’s initial attempts at transferring might outline the overall purpose of the task and one or two key strategies to prevent skin damage and injury (see Chapter 3). As some overall ability to transfer is developed, instructions can become more specific. Instructions might include suggestions for positioning of the hands or for timing of the lift. Instructions need to be articulated according to patients’ education and understanding of the task. Some will benefit from understanding the intricacies of movement and being cued to increase their awareness of internal feedback systems. For example, they might find it helpful to think about the position of the head in relation to the hips, or the amount of shoulder depression and trunk forward lean associated with a successful transfer. Others will be better served by the provision of external cues based on vision. For example, they might look down between their legs to ensure they have moved far enough forward in the wheelchair prior to transferring. (If the patient has moved far enough forward they should not be able to see the seat between their thighs.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree