Traditional Procedures for the Repair of Hallux Abducto Valgus

Bradley D. Castellano

Joe T. Southerland

In the early history of surgical treatment for hallux abducto valgus deformity, the procedures consisted primarily of osseous resection of the medial aspect of the metatarsal head or the proximal phalangeal base with or without associated soft tissue repair or soft tissue correction alone. Although repair of the condition has become more sophisticated, some of these procedures remain suitable repair techniques. In particular, the simpler approaches have been deemed preferable in older patients, in whom osteotomies may pose a higher degree of risk. However, the indications for these procedures are certainly broader than just in the elderly, and their use may be appropriate in patients with a wide age range.

EARLY PROCEDURES

The early means of surgical treatment for hallux abducto valgus deformity often consisted of soft tissue procedures that preceded true bunionectomy. Surgical excision of the bursa overlying the head of the first metatarsal was advocated (1), but in the early to mid-1800s, controversy existed about whether bursectomy should be combined with exostectomy of the metatarsal head.

Reverdin described exostectomy of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (2), and in 1881 he reported on two cases in which he used a wedge osteotomy of the first metatarsal head. Sagittal plane resection of the medial eminence of bone of the first metatarsal head was then made popular by Moeller, who described the surgical procedure performed by Max Shede between 1884 and 1892 (3). Shede’s simple exostectomy was performed on the medial first metatarsal head, and an elliptic skin resection was used to aid in relocation of the hallux. Forceful manipulation of the toe was performed intraoperatively to release the shortened lateral structures of the joint. Although Bromeis noted that correction of an abducted hallux was rarely obtained using simple exostectomy (4), he nonetheless reported satisfactory results in 87% of his cases using Shede’s procedure.

SILVER BUNIONECTOMY

In 1923, Silver described his method of capsulorrhaphy of the first metatarsophalangeal joint for hallux valgus repair (5). Silver was probably influenced by Fuld, an ophthalmic surgeon, who proposed abductor hallucis tendon transfer for the repair of hallux abducto valgus (6). Furthermore, the philosophy of joint preservation may have been a reaction to the earlier arthroplasty procedures, which Silver found to be indiscriminate and nonspecific. Later, prominent surgeons such as McBride (7), Lapidus (8), and Mitchell et al. (9) noted and used Silver’s technique to supplement their own procedures. The technique was remarkable because medial exostectomy or at least decortication of the medial head of the first metatarsal was performed. Supplemental to this, the medial joint capsule was reinforced with the abductor hallucis tendon and the inferior capsular attachments by relocating the tendon insertion to a more dorsal position on the proximal phalangeal base. Fuld detached all the structures attached to the abductor tendon before its transfer (6). Silver noted the significance of the lateral position of the sesamoid apparatus and attempted its relocation by maintaining the attachment of the flexor plate to the abductor tendon. Finally, the tendon of adductor hallucis and the lateral joint capsule were sectioned with a U-shaped capsulotomy.

Silver immobilized patients for prolonged periods in an attempt to maintain the correction obtained with this primarily soft tissue procedure. However, this prolonged period of immobilization is not necessary today because numerous different types of splints are available to help maintain the hallux in the corrected position. Extended splinting may be helpful in allowing the capsular tissues to adapt to the new position, but it may also contribute to joint stiffness.

Indications

The Silver bunionectomy procedure, or a slight modification thereof, is frequently combined with osteotomies of the first metatarsal or proximal phalanx of the hallux. As an

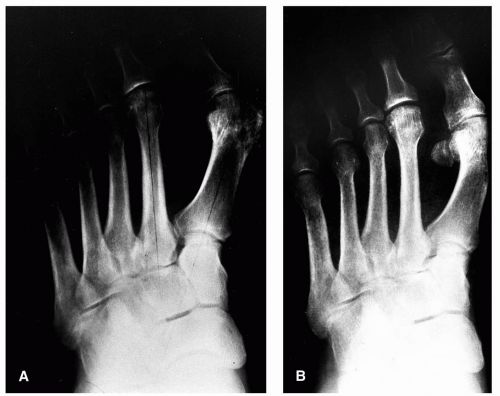

isolated procedure, it is best used in the presence of a true dorsomedial or medial prominence of the first metatarsal head with little hallux valgus or increase in the first intermetatarsal angle. Less than favorable results occur in most other situations. Patients undergoing Silver bunionectomy should be warned that cosmetic results are generally poor because the hallux position is unaffected or is sometimes made worse if the medial capsule is weakened by the procedure (Fig. 1). The Silver bunionectomy provides few advantages over other, slightly more involved techniques.

isolated procedure, it is best used in the presence of a true dorsomedial or medial prominence of the first metatarsal head with little hallux valgus or increase in the first intermetatarsal angle. Less than favorable results occur in most other situations. Patients undergoing Silver bunionectomy should be warned that cosmetic results are generally poor because the hallux position is unaffected or is sometimes made worse if the medial capsule is weakened by the procedure (Fig. 1). The Silver bunionectomy provides few advantages over other, slightly more involved techniques.

MCBRIDE BUNIONECTOMY

In 1928, McBride described a procedure similar to the Silver bunionectomy, but he added a transfer of the conjoined tendon of the adductor hallucis and the fibular head of the flexor hallucis brevis to the dorsum of the first metatarsal head. The fibular sesamoid was removed on occasion as well, and, if it was not excised, the lateral head of the flexor hallucis brevis was tenotomized (7,10). McBride believed that eliminating the lateral joint contracture was essential to allow the first metatarsal to resume a more rectus alignment. During this time, much attention was paid to the tendon transfer described by McBride. Although some surgeons may have interpreted this maneuver as a means of attempting to reduce the intermetatarsal angle, McBride himself stated that its purpose was to ensure that the lateral tendinous structures would not serve as a potential deforming force in the future (11).

Modification of the McBride bunionectomy has generally been concerned with the method of adductor tendon transfer and the performance or omission of fibular sesamoidectomy. In a later publication, McBride indicated that the adductor tendon was sutured into the lateral aspect of the first metatarsal, as opposed to dorsally (11). DuVries modified the procedure by suturing the adductor hallucis tendon to the adjacent capsular structures of the first and second metatarsophalangeal joints (12). McGlamry and Feldman discussed the transfer of the adductor hallucis across the dorsum of the metatarsal (13). The tendon was then sutured into the medial joint capsule to aid in repositioning the sesamoid apparatus.

Removal of the fibular sesamoid has been widely discussed. The proponents of fibular sesamoidectomy argue that this method provides effective release of the lateral contracture of the first metatarsophalangeal joint, even in advanced deformity. In contrast, fibular sesamoidectomy has been shown to be a risk factor for hallux varus when the procedure is combined with a rounded first metatarsal head (14). The evolution of anatomic dissection techniques has provided the surgeon with a means by which the lateral joint contracture may be released without indiscriminate removal of the fibular sesamoid. Nonetheless, excision of the fibular sesamoid may be required when the standard soft tissue release is inadequate to alleviate lateral joint contracture and when the fibular sesamoid is deformed or arthritic. Because removal of the sesamoid does result in a significant alleviation of joint tension and contracture, this technique may also

be important in some older or compromised patients, in whom avoiding an osteotomy may be preferable.

be important in some older or compromised patients, in whom avoiding an osteotomy may be preferable.

Indications

In general, the McBride procedure is usually discussed with regard to whether or not the fibular sesamoid should be excised. Lateral release without excision of the sesamoid is often referred to as a modified McBride procedure. As an isolated procedure, this approach may be used in patients of any age with a painful bunion deformity, who have little hallux abducto valgus and normal to mild increase in the intermetatarsal angle. Otherwise, the procedure is most commonly employed as a step in joint release in conjunction with metatarsal osteotomy procedures.

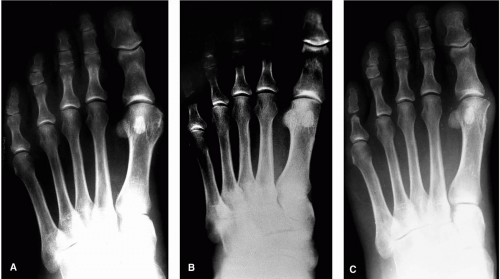

The true McBride procedure, consisting of removal of the fibular sesamoid, may be an option for older patients who may be at greater risk for complications with an osteotomy because of poor bone stock, unstable gait, previous osteomyelitis of the metatarsal head, or other special situations. The key to determining whether the McBride procedure would be potentially successful for any given deformity is the flexibility of the first ray. The ability of the surgeon to reduce the intermetatarsal angle with a soft tissue release alone is predicated on the first ray’s being flexible and reducible. If the first ray possesses a limited range of motion, then success is less likely. Flexibility is usually assessed by evaluating the sagittal plane mobility of the first ray. Should good motion be available in this plane, then the patient will most likely possess adequate mobility in the transverse plane to allow reverse buckling at the first metatarsophalangeal joint and reduction of the intermetatarsal angle. However, if the first ray is rigid, then one can anticipate a limited degree of reduction of the intermetatarsal angle and generally a disappointing correction (Fig. 2).

In younger patients, the modified McBride procedure results in reduced healing time and a quicker return to function, as compared with more frequently used osteotomy procedures, although the procedure may not always result in muscle tendon balancing about the first metatarsophalangeal joint, and a recurrence of deformity may be noted (Fig. 3). This thought has persuaded some surgeons that the modified McBride procedure is not well suited in younger patients (14,15). A capital osteotomy with a small degree of transposition may be considered as an alternative. However, it would be difficult to argue against using the modified McBride procedure when the intermetatarsal angle is normal, yet a problematic bunion is present.

Technique

Both the medial and lateral sides of the first metatarsophalangeal joint are easily approached from a single dorsolinear incision made just medial to the extensor hallucis longus tendon. The dissection approach is a standard technique that is employed by many surgeons and is discussed in the section on anatomic dissection of the first ray (see Chapter 7). Several important points should be considered in the process. One needs to ensure that the adductor tendon is completely released and is not tethered to the proximal aspect of the fibular sesamoid. The fibular sesamoidal ligament needs to be transected to relieve lateral contracture completely and to allow the flexor apparatus to relocate beneath the first metatarsal head. If continued lateral contracture persists, then the segment of the flexor hallucis brevis between the fibular sesamoid and the proximal phalanx may be sectioned. Persistent contracture indicates a need to consider removal of the fibular sesamoid. A judicious resection of the dorsomedial eminence should be performed. If significant prominence persists after exostectomy, then an osteotomy may be indicated. Transfer of the adductor tendon may enhance the overall repair and the balance of the tissues about the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Complications

Removal of the fibular sesamoid has often been considered a predisposing factor for the development of hallux varus. However, the incidence of this complication is probably not as great as imagined. Pfeffinger reported an 8% hallux varus rate in 72 McBride procedures (16), although Feinstein and Brown found only 10 cases of hallux varus in 878 cases (17). Nine of the 10 cases were the result of McBride bunionectomies. Unfortunately, most studies do not compare the rate of complications with those achieved with osteotomy techniques, thereby making an absolute determination of the influence of fibular sesamoidectomy with hallux varus less certain.

Other complications of fibular sesamoidectomy may include subsequent tibial sesamoiditis or the development of a plantar hyperkeratosis beneath the tibial sesamoid. Usually, these problems are well managed with accommodative insole devices.

Recurrence of the hallux abducto valgus deformity may be seen regardless of whether the fibular sesamoid was removed. In younger patients undergoing the modified McBride procedure, the medial capsular tissues may not provide enough stability to resist lateral deviation of the hallux in later years. When the true McBride technique is employed, patients generally have a greater degree of deformity present preoperatively that one is attempting to correct by redirecting the vectors of force across the first metatarsophalangeal joint with soft tissue alone. In this instance, an element of persistent instability may be noted that may not be present in other procedures when an osteotomy is performed.

KELLER JOINT RESECTION ARTHROPLASTY

Joint resection procedures were first performed in the early 1800s. Fricke described a complete arthrectomy with resection of both sides of the first metatarsophalangeal joint along with the sesamoids (18). This operation was reported to be a perfect success. In 1877, Hueter described a procedure in which the first metatarsal head was resected for hallux valgus deformity (19). Keller believed that the resection of the proximal phalangeal base was a less destructive approach to hallux valgus repair (20), because complete resection of the first metatarsophalangeal joint created complications such as metatarsalgia and flail hallux. Furthermore, he believed that weight was primarily borne by the heel and the first and fifth metatarsal heads, hence the impetus to preserve the metatarsal head. The Keller procedure initially entailed resection of the proximal half of the proximal phalanx of the hallux. Brandes subsequently reported a more significant two-thirds resection of the proximal end of the phalanx (21). Resectional arthroplasty was supplemented with implantation of durillium and then silicone joint prostheses in later years. With the addition of numerous modifications, the resectional arthroplasty often bears little resemblance to the original Keller procedure, except for the removal of the base of the proximal phalanx.

Opinion varies regarding the success and utility of the resection arthroplasty, probably more so than with any other procedure for the repair of hallux abducto valgus deformity. Much of this controversy results from some of the complications encountered with the procedure. These complications may be real, but they are probably overemphasized and the incidence overstated, particularly with the modifications in technique that are available. Today, one may perform the procedure with greater reliability, and most of the historical problems witnessed with this approach can be minimized. The modifications of the procedure can make a significant difference in the success or failure of the procedure.

Indications

The indications for resection arthroplasty are not exclusively based on the patient’s age. However, the significant indications based on degenerative joint disease and osteopenia may be more frequently encountered in the older patient. More recently, the procedure has been considered as a primary means of addressing the “geriatric bunion.” This term conjures the image of an older patient who may be less stable or propulsive in ambulation, who may have osteopenic bone or cystic degeneration of the metatarsal head, who may present with significant deformity, and in whom an osteotomy may create too great a risk in the perioperative and postoperative periods. In such patients, resection arthroplasty provides a viable means of safely repairing the deformity and providing a lasting correction. The advantages of the procedure include avoidance of an osteotomy, avoidance of a joint prosthesis, reduction in convalescence, and ablation of arthritic or hypertrophic bone. Several studies have reported a greater than 75% satisfaction rate with the Keller resection arthroplasty. In these particular studies, the average age has ranged from 43 to 66 years (22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree