Total Scapulectomy and Reconstruction Using a Scapular Prosthesis

Panayiotis J. Papagelopoulos

Andreas F. Mavrogenis

Tumors of the scapula often become quite large before being brought to a physician’s attention. In the early stages, they are usually contained by a cuff of muscle (infraspinatus, subscapularis, and supraspinatus). Tumor extension to the chest wall, axillary vessels, proximal humerus, glenohumeral joint, and rotator cuff may follow during disease progression (1,3,10,13,18,19).

The first reported scapular resection was a partial scapulectomy performed by Liston in 1819 for an ossified aneurysmal tumor. Since then, most shoulder girdle resections are performed for low-grade tumors of the scapular and periscapular soft tissue sarcomas (7,8,9,10). After the initial description of the Tikhoff-Linberg resection for osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma of the proximal humerus or scapula in the 1980s, a variety of new techniques and modifications of shoulder girdle resections have been developed, and several classification systems have been proposed (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20). The earlier systems were purely descriptive and related almost exclusively to the bones resected. In addition, they did not accommodate or reflect concepts or terminology that have developed in the past 2 decades in orthopedic oncology. The present surgical classification system was described by Malawer in 1991 (Table 27.1) (7). This classification was based on the current concept of surgical margins (intra-articular vs. extra-articular), the relationship of the tumor to anatomic compartments (intracompartmental vs. extracompartmental), the status of the glenohumeral joint, the magnitude of the individual surgical procedure, and consideration of the functionally important soft tissue components.

INDICATIONS

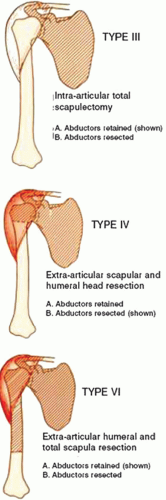

Total en bloc scapulectomy and limb-salvage surgery are indicated for most low- and high-grade primary sarcomas of the scapular and soft tissue sarcomas that secondarily invade the bone when an adequate soft tissue cuff can be obtained for surgical margins, that is, Type III (intra-articular total scapulectomy), Type IV (extra-articular scapulectomy and humeral head resection), and Type VI (extra-articular humeral and total scapular resection) resections (Fig. 27.1).

It may be performed if the potential results are equivalent to or better than amputation, with preservation of good elbow and hand function.

TABLE 27.1 Surgical Classification of Shoulder Girdle Resections | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 27.1 The three types of total scapulectomy according to Malawer et al (7). |

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications for the procedure include tumor extension into the axilla with involvement of the neurovascular bundle, inability to spare the required muscles, and the patient’s inability or unwillingness to tolerate a limb-salvage operation.

Although a functioning deltoid is recommended for use of a scapular prosthesis, resection of the axillary nerve should not be considered an absolute contraindication for scapular replacement (14,21).

Relative contraindications may include chest wall extension, pathological fractures of the scapular or proximal humerus, lymph node involvement, and an inappropriately placed biopsy that has resulted in infection or extensive hematoma and tissue contamination.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Physical examination, plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are important means for evaluation of a patient with a tumor of the shoulder girdle. The MRI can help estimate whether there will be enough soft tissue remaining for the reconstruction. For large tumors involving the proximal humerus, a venogram may also be useful if there is evidence of distal obstruction suggesting tumor thromboembolism (analogous to tumor thromboembolism seen in the iliac vessels and inferior vena cava from large pelvic sarcomas).

The goals of preoperative templating are to guide both proper sizing of the humeral and custom-made scapular components, as well as intraoperative restoration of the soft tissue balance of the shoulder joint. CT scan data are used to design the prototype model to manufacture the custom scapular prosthesis. Alternatively, nonmodular scapular prostheses are available in two sizes, adult and pediatric. Thinking of the glenohumeral articulation, either a reverse constrained shoulder replacement (i.e., the head on the scapular and a captive cup in the proximal humeral prosthesis) or a nonconstrained replacement with a shallow glenoid and a large head on the proximal humeral prosthesis (much like a Neer II prosthesis) can be performed. However, when a large amount of periscapular soft tissue is resected, a constrained shoulder joint prosthesis is indicated.

SURGERY

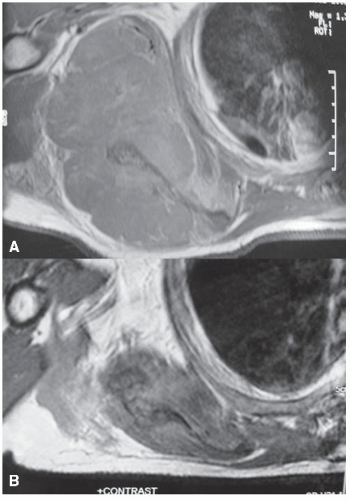

Limb-salvage surgery at the shoulder girdle is more difficult than a forequarter amputation. The surgical options are technically demanding and fraught with potential complications. One should be experienced with all aspects of shoulder girdle anatomy. Anatomic landmarks to be considered include the clavicle, acromion, acromioclavicular joint, scapular spine and the borders of the scapular, proximal humerus, and glenohumeral joint. We describe herein the procedure of intra-articular total scapulectomy and constrained reverse total scapular reconstructions after resection of a sarcoma of the right scapular (Fig. 27.2A,B).

Patient Positioning

The patient is placed in the lateral position on a standard operating room table secured with commonly available positioners (Fig. 27.3A,B). A Foley catheter is inserted, and preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is administered. An axillary roll is inserted distal to the opposite axilla under the chest wall. The dependent arm is placed on a well-padded arm board in an extended position.

The arm is prepared and draped free for intraoperative manipulation. It may be placed on a bolster or a sterile Mayo stand.

Incision

A combined anterior and posterior approach is utilized (utilitarian shoulder girdle incision), as it permits wide exposure and release of all muscles attached to the scapular including the rhomboids, latissimus dorsi, and trapezius. The utilitarian shoulder girdle incision is identical to that of the Tikhoff-Linberg procedure for resection of the proximal humerus. This incision, or parts of it, permits safe exposure for resection and reconstruction of most shoulder girdle tumors and safe exposure of the axillary vessels and brachial plexus. The surgical incision should incorporate the biopsy tract and remove it with the surgical specimen.

Anteriorly, the incision begins at the junction of the inner and middle thirds of the clavicle and continues over the coracoid process, along the deltopectoral groove at the anteromedial aspect of the deltoid muscle, and down the arm over the medial border of the biceps muscle.

Posteriorly, the incision begins over the midclavicular portion of the anterior incision, crosses the suprascapular area, runs over the lateral aspect of the scapular along the neck of the glenoid, proceeds distally to

the inferior tip of the scapular, and curves toward the midline. One skin flap is mobilized medially toward the vertebral border of the scapular and the other laterally to expose the entire scapular and its covering fascia and musculature. To preserve vascularity to the skin, care should be taken not to make the flaps any wider than necessary.

the inferior tip of the scapular, and curves toward the midline. One skin flap is mobilized medially toward the vertebral border of the scapular and the other laterally to expose the entire scapular and its covering fascia and musculature. To preserve vascularity to the skin, care should be taken not to make the flaps any wider than necessary.