CHAPTER 35 Total Hip Arthroplasty in the Young Active Patient With Arthritis

Introduction

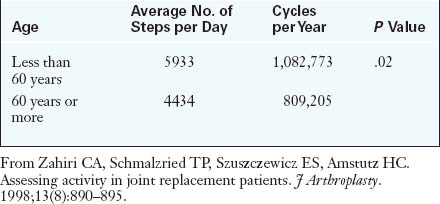

Although indicating a young patient for THA is always disheartening, the good news is that patients can usually expect excellent pain relief and a high level of performance in a reproducible and predictable manner. Long-term results are tempered by wear-induced failures, which are a function of the increased number of loading cycles as a result of increased activity levels (Table 35-1) and increased life expectancies (Table 35-2). This data shows that there is a higher risk of failure in a younger patient during the subsequent 15 years after THA.

Table 35–2 15-Year Survival of Patients with Total Hip Arthroplasties

| Age at Surgery | Percentage of Patients Still Alive | Percentage of Arthroplasties Still in Place |

|---|---|---|

| 45 years | 96% | 77% |

| 65 years | 72% | 92% |

From Berry DJ, Harmsen WS, Cabanela ME, Morrey BF. Twenty-five-year survivorship of two thousand consecutive primary Charnley total hip replacements: factors affecting survivorship of acetabular and femoral components. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:171–177.

This chapter will discuss the inherent challenges involved when performing a THA in a young patient.

Imaging and diagnostic studies

We prefer to routinely obtain five radiographs for preoperative evaluation:

Anesthesia and surgical technique

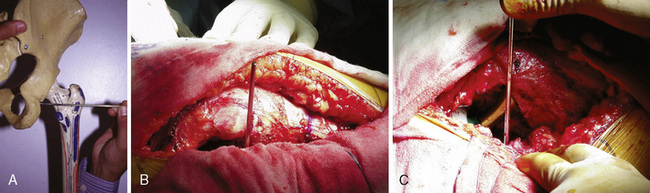

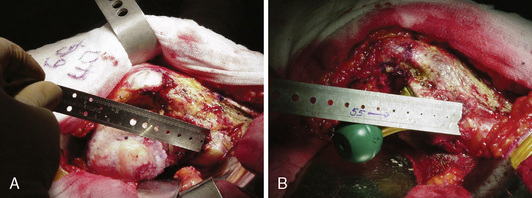

For the assessment of limb-length discrepancy, we prefer the method described by Ranawat and colleagues. This technique involves the use of the posterior approach. After the initial dissection and release of the short external rotators, the inferior capsule is incised at the 6-o’clock position to expose the posteroinferior lip of the acetabulum. A  -inch Steinmann pin is inserted into the posterior infracotyloid groove (Figure 35-1, A through C); this represents the bony groove inferior to the posteroinferior lip of the acetabulum. The pin is placed initially at an angle of approximately 60 degrees until it touches the ischium, and it is then made vertical and allowed to slide along the bone into the infracotyloid groove. The pin is kept vertical and viewed end-on from above, and then a mark is made on the greater trochanter before hip dislocation (see Figure 35-1, B). The hip is then dislocated. The center of the femoral head is marked with electrocautery, and the distance between the center and the lesser trochanter is noted and compared with the calculation made during the preoperative planning (Figure 35-2, A). The neck resection is now completed in accordance with preoperative templating.

-inch Steinmann pin is inserted into the posterior infracotyloid groove (Figure 35-1, A through C); this represents the bony groove inferior to the posteroinferior lip of the acetabulum. The pin is placed initially at an angle of approximately 60 degrees until it touches the ischium, and it is then made vertical and allowed to slide along the bone into the infracotyloid groove. The pin is kept vertical and viewed end-on from above, and then a mark is made on the greater trochanter before hip dislocation (see Figure 35-1, B). The hip is then dislocated. The center of the femoral head is marked with electrocautery, and the distance between the center and the lesser trochanter is noted and compared with the calculation made during the preoperative planning (Figure 35-2, A). The neck resection is now completed in accordance with preoperative templating.

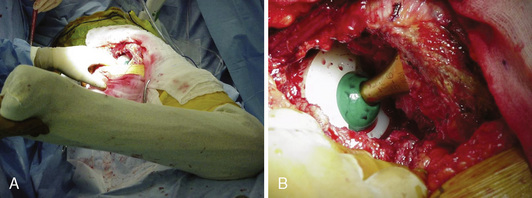

After bone preparation and the placement of the trial implants, the offset and the distance from the center of the head to the lesser trochanter are assessed (see Figure 35-2, B). After reduction, the component position is assessed with the use of the combined anteversion test (Figure 35-3, A and B). This test measures the angle of internal rotation required for the femoral head to be coplanar with the face of the acetabulum with 10 degrees of flexion and 10 degrees of adduction. Normally, the angle is between 35 degrees and 45 degrees of internal rotation for women and between 25 degrees and 35 degrees for men.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree