Total Ankle Arthroplasty in the Valgus Ankle

James K. DeOrio

INTRODUCTION

The valgus ankle is less commonly seen than the varus ankle. Trauma, posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD), and, more infrequently, the “ball-and-socket” ankle joint are the major categories for the valgus ankle. Ankle sprains fall within the trauma etiologies, and can lead to long-standing ankle instability, resulting commonly in a varus ankle. Occasionally, however, this ankle instability can lead to a valgus ankle deformity.

INDICATIONS

The indications for the treatment of the valgus ankle are pain and/or a significant alignment problem which is known to lead to increased deformity and pain. Although some authors have placed limits on the amount of correction attainable, we have found that with the judicial use of adjunctive procedures, we can correct coronal plane deformities to match the results of those ankles with no deformity.1

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications for the treatment of these deformities have been previously discussed in this book and includ poor skin, peripheral vascular disease, generally patients younger than 35 years, type 1 diabetes, neuromuscular paralysis, and avascular necrosis of the talus and/or distal tibia. The avascular necrosis of the distal tibia seen in plafond-type injuries may be overcome with a modular-type tibial stem component.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION, PLANNING, AND CONCEPTS

As usual the preoperative planning should include standing anteroposterior view, mortise and lateral views of both ankles, a calcaneal Saltzman view, standing lower leg views when there is a deformity above the ankle, and vascularity tests when there are no or faintly palpable pulses (consider a vascular consultation as well). A computed tomography scan may be necessary when looking for adjacent joint arthritis, and a magnetic resonance imaging scan is utilized when assessing the talus or distal tibia for vascularity.

STEPWISE TECHNIQUE

FIBULAR LENGTHENING

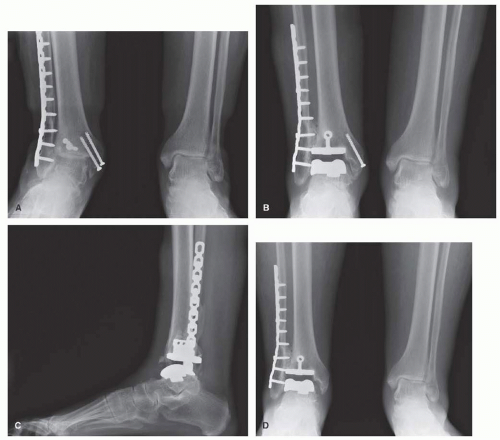

Trauma is a frequent cause of a degenerative ankle in valgus position. Commonly the result of a pronation external rotation injury, the lateral plafond is damaged and the fibula is fractured, usually with shortening. Such was the case in Figure 10.1, where the lateral plafond was too comminuted to really avail itself to reconstruction, and the fibula, although fixed, was not brought down to length along with syndesmosis fixation. Thus, the question in the case of this 71-year-old, osteoporotic woman who was slightly demented is, how many surgeries should you undertake in order to make her better? The decision was made to simply resurface the ankle. The valgus deformity was corrected to 3°. In an effort to avoid gross instability, the syndesmosis was prepared and bone graft, without fixation, was laid between the fibula and the talus for long-term stability.

In retrospect, a lengthening of the 7-mm shortened fibula could have been done by simply taking out the distal screws, cutting the fibula, distracting the fibula distally, and replanting the screws through the plate. Syndesmotic screws could also have been placed to support that lateral side and get the patient out of valgus, and bone graft could have been used to fill in the defect in the fibula. This procedure of lengthening the fibula is similar to that done for the overcorrected clubfoot.2 Those patients did well with no significant complication, and all had the ability to wear normal shoes. Unfortunately, in this case, because not enough was done to correct her deformity, 2.5 years after her arthroplasty (Fig. 10.1D), she required an arthroscopic debridement of her medial gutter.3 This is not an uncommon phenomenon when balance after total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) is not fully obtained. In contrast to this patient is the one seen in Figure 10.2 with a 40° severe valgus deformity secondary to a ball-and-socket ankle joint. Here, doing this case without a fibular lengthening osteotomy to support the ankle would not have been possible.

TIBIAL-FIBULAR OSTEOTOMY

Unless the condition is particularly severe, that is, more than 20° of valgus, an opening lateral tibial-fibular osteotomy is usually not necessary. I have, however, done this procedure with good results.4 Nonetheless, because of the proximity of the lateral and anterior wounds, staging the osteotomy and the ankle replacement is quite reasonable. The same logic applies to the closing-wedge medial tibial osteotomy, albeit one can plate the medial side of the tibia from the anterior TAA wound. If they are chosen to be done simultaneously, percutaneous screw fixation of the medial plate may be preferable to a large dissection of the medial flap.

ARTHRODESES

Another frequent source of a valgus degenerative ankle is PTTD with a stage IV ankle. Here the valgus position of the hindfoot has gradually worn away the lateral tibial plafond and placed the patient in valgus with little or no cartilage in the lateral ankle joint. Getting the ankle in place is only half of the operation. The other half are the procedures done in addition to the ankle placement in order to regain balance for the ankle.5 These adjunctive procedures may include a talonavicular (TN) or subtalar arthrodesis. Here the deformity is judged to be too severe for soft tissue balancing. The TN joint is approached and cleaned out through the same anterior incision

in the ankle. I like to fix these in an anatomic position with two fully threaded screws inserted from the medial and dorsal medial navicular bones into the talus. The joint can be prepared early, but it is best to have the ankle in position before the TN joint is fixed.

in the ankle. I like to fix these in an anatomic position with two fully threaded screws inserted from the medial and dorsal medial navicular bones into the talus. The joint can be prepared early, but it is best to have the ankle in position before the TN joint is fixed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree