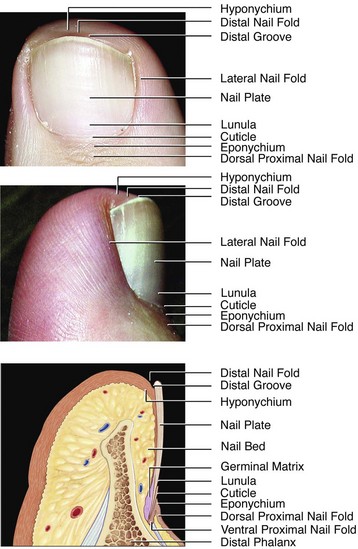

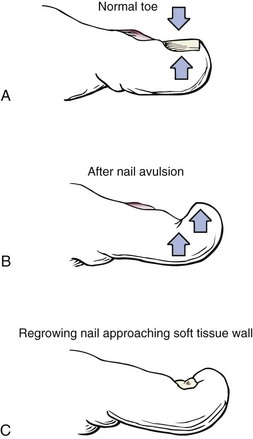

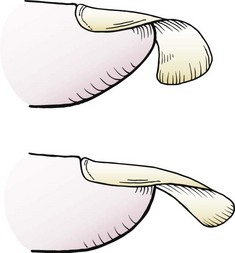

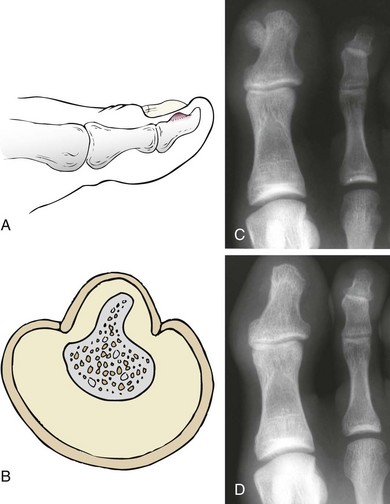

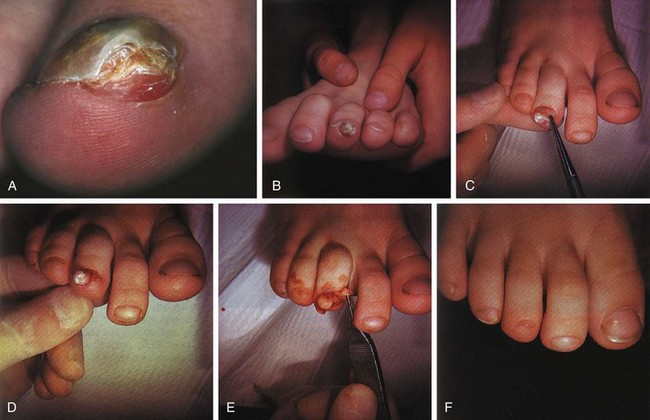

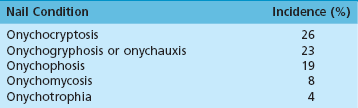

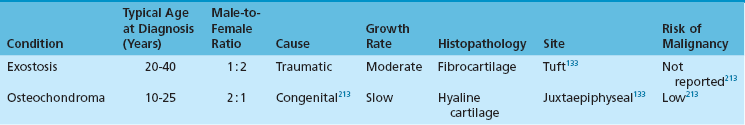

Chapter 11 DERMATOLOGIC AND SYSTEMIC NAIL DISORDERS GENETIC DISORDERS WITH NAIL CHANGES ONYCHOPATHIES AND OTHER COMMON NAIL ABNORMALITIES Conservative and Surgical Treatment The nails are special cutaneous appendages that have the primary function of protecting the distal phalanx. Only primates have toenails, and whether the first primates with flat nails had an advantage over their peers by being able to remove parasites better from their bodies (thus promoting their evolutionary superiority) is a matter of fascinating speculation.232 Although few studies of physicians’ reports have documented the frequency of nail disorders, Krausz123 did examine the incidence of nail disorders (Table 11-1). During 41 years of practice, Krausz reported on 7670 patients displaying one or more nail disorders.153 Table 11-1 Data from Krausz CE: Nail survey (1942-1970). Br J Chir 35:117, 1970; Nzuzi SM: Common nail disorders. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:273–294, 1989. The toenail or nail plate is composed of several layers of dense, overlapping keratinized cells. There are three layers, each originating from a different area of the nail unit. The relatively thin dorsal layer is stiff and brittle and covers the relatively thick softer middle layer. The deep layer is thought to be derived in part from the nail bed itself.95,113,114 The nail plate differs from hair or skin in that it does not desquamate skin cells. The hardness of the nail plate can be attributed to its high sulfur content56 and to the paucity of water within the plate. Although the nail plate is 10 times more permeable to water than the skin, the nail plate, unlike the skin, has a low fat content and thus cannot retain water.12 The normal nail plate grows distally approximately 0.03 to 0.05 mm/day, and it has a thickness of 0.5 to 1 mm.107 The nail plate is supported by the nail unit,61 or perionychium,232 an area of epithelial tissue that is divided into four components (Fig. 11-1)228: nail bed, hyponychium, proximal nail fold, and nail matrix. Synonyms are common for various anatomic units (Box 11-1). The nail plate lies on the nail bed, a roughened epithelial surface consisting of longitudinal grooves that interdigitate with corresponding grooves on the undersurface of the toenail. This interdigitation firmly bonds the nail plate to the nail bed. The nail bed or sterile matrix has only one or two layers of germinal cells, which produce the nail plate.232 At the distal end of the nail bed, where the nail bed and the nail plate separate, a smooth border of skin called the hyponychium forms a seal between the distal end of the toenail and the nail bed. On the tibial and fibular borders of the toenail, the nail plate is surrounded by epidermal skin folds termed lateral nail folds. The base of the toenail is covered by the proximal nail fold, a complex structure that has germinal cells on the proximal half of the plantar surface of the nail fold.232 The dorsal surface of the nail fold is composed of skin on the dorsal surface of the toe. On the plantar surface of this fold, the eponychium forms a thin surface that attaches to the nail plate. The distal surfaces of these two components of the proximal nail fold comprise the cuticle. The nail matrix or germinal matrix is the main germinal area of the toenail. The germinal matrix extends from a point just distal to the lunula and as far laterally as the entire width of the nail plate,55 and it extends 5 to 6 mm proximally to the edge of the cuticle and closely borders the insertion of the long extensor tendon and the interphalangeal joint.95 The nail matrix is seen beneath the nail plate as the lunula—the opaque, crescent-shaped area at the base of the nail. It lacks color because it is less vascular than the heavily vascularized nail bed. Distally, the nail matrix is contiguous with the nail bed. The nail matrix is covered by a small epidermal surface but does not have the epidermal ridges characteristic of the nail bed. At the distal end of the lunula, the nail matrix terminates. As noted above, at the proximal margin of the matrix, a small area on the plantar surface of the proximal nail fold appears to contribute to the growth of the nail plate.95,134,182 This is important to remember when trying to permanently ablate the nail by removing the germinal matrix from which the nail grows. Most matrix germination occurs between the apex of the matrix and the distal border of the lunula. The area covered by the proximal nail fold forms the thin dorsal layer of the nail plate. The area of the lunula produces the thicker, softer middle portion of the nail plate and joins with the dorsal area to form the nail plate.95 Although the germinal matrix is the major origin for toenail growth, additional microscopic germinal areas of growth may be present within the lateral nail folds and the distal nail bed.113,114,126 These produce a thin layer of the ventral toenail plate, a factor that occasionally accounts for postoperative regrowth.55,95,134 The germinal matrix cells of the nail plate are oriented longitudinally. Because of pressure from the proximal nail fold, the nail plate grows distally rather than in an elevated direction. However, if the nail matrix is injured or altered because of trauma or surgery, the nail plate may grow in an abnormal direction. Likewise, the nail plate gives a certain rigidity to the soft tissue of the distal part of the toe. If the toenail is removed or ablated, the distal nail bed and soft tissue can grow in an elevated direction because of lack of dorsal pressure from the nail (Fig. 11-2). As the new nail plate begins to grow distally, it can abut these soft tissues and lead to a club nail or an ingrown toenail. Common diseases involving the nail include infection, psoriasis, contact dermatitis and eczema, tumor, trauma, and general or systemic diseases.216 A systematic review of nail disorders by Pardo-Castello and Pardo165 provides a useful classification for both common and uncommon nail abnormalities and also discusses disorders caused by trauma and neoplasia. The classification includes the following: Nzuzi154 presented the following logical classification of common nail disorders (onychopathies) based on the anatomic structures primarily involved (Box 11-2): Skin disorders involving the nails are usually within the province of the dermatologist, and systemic disorders involving the nails are typically within the internist’s scope of practice. Few of these entities require localized or systemic treatment. Nonetheless, an awareness of the underlying pathologic processes and an understanding of the nail changes associated with specific dermatologic and systemic disorder assists in making a definitive diagnosis. Pathologic conditions of the toenail are defined in Box 11-3, and terms describing infections are defined in Box 11-4. Psoriasis of the toenails often accompanies cutaneous disease, and patients often mistake it for fungal involvement of the nail (Fig. 11-4A-E). Involvement of the nails is seen in 80% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and in 30% of patients who have psoriasis without arthritis.176 The most severe form of nail involvement with psoriasis, which sometimes involves shedding and loss of the nail (onychomadesis), is associated with arthritic changes. Many patients without arthritic changes who have psoriasis have the following abnormal findings in either their toenails or their fingernails225,226: Treatment of psoriatic nail changes of the feet is generally unsatisfactory. Intralesional injection of corticosteroids may be effective for treating psoriasis in fingernails,25 but similar therapy for involved toenails is administered less often. Bacterial infections occur commonly in the feet and are divided into primary and secondary pyodermas. Impetigo is a superficial skin infection that is often caused by Staphylococcus and/or Streptococcus species, and it usually affects younger children. The typical lesion consists of a thin-walled vesicle on an erythematous base. The vesicles form yellow crusts, and peripheral extension results in irregular serpiginous lesions. The lesions are common on the face but can occur anywhere on the body except the palms and soles. Ecthyma is a form of pyoderma that begins as small vesicles or pustules on an erythematous base and quickly develops a purulent, irregular ulcer. These lesions are common on the lower extremities and, as with impetigo, readily respond to systemic antibiotics. Burow compresses are helpful in removing the crusts, and topical antibiotic ointment is usually applied several times a day (Box 11-5). The infection should be carefully investigated to determine the presence of any underlying systemic disorders, such as diabetes, lymphoma, or an immunodeficiency syndrome, that could predispose the patient to such cutaneous infections. Amonette and Rosenberg5 found that the best treatment regimen was topical management with a combination of bed rest, exposure to air, and application of silver nitrate solution, Castellani paint, and gentamicin sulfate cream. Erythrasma is often seen in intertriginous areas, such as the web spaces. The causative organism is Corynebacterium minutissimum, which produces a well-demarcated, reddish brown, fine desquamation that fluoresces orange-red or coral-pink under a Wood lamp. Wearing loose stockings and shoes and using antibacterial soaps usually prevent this infection or eliminate it after it has been established. Treatment occasionally requires appropriate oral antibiotics. With the sudden arrest in longitudinal nail growth, a transverse sulcus, a Beau line develops, which is 0.1 to 0.5 mm deep (Fig. 11-7). With further growth of the nail plate, the Beau line progresses distally. This is associated with severe febrile episodes, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, trauma, Hodgkin disease, and infections such as malaria, rheumatic fever, syphilis, leprosy, typhoid fever, and various parasitic infections. Mees lines are also associated with growth arrest of the nail plate. Mees lines are horizontal striations that typically involve more than one nail. They are usually 1 to 3 mm wide and are associated with Hodgkin disease, myocardial infarction, malaria, and arsenic and thallium poisoning.153,154 In the Terry nail, characteristic changes involve opacification of the nail plate with a 1- to 3-mm pinkish band at the distal edge of the nail plate. Often, this condition is connected with chronic changes associated with diabetes mellitus and liver disease (see Fig. 11-7B). Kosinski and Stewart122 described pathologic nail conditions that are often associated with systemic disease entities. These nail changes may be manifested in cardiovascular disorders (yellow nail syndrome or splinter hemorrhages, see Fig. 11-7C and D and Table 11-2), hematologic diseases (Table 11-3), endocrine disorders (Table 11-4), connective tissue diseases184 (Table 11-5), local and systemic infections (Table 11-6), neoplasia (Table 11-7), and renal, hepatic, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal disorders (Table 11-8). Table 11-2 Cardiovascular Disorders and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Table 11-3 Hematologic Disorders and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Table 11-4 Endocrine Disorders and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Table 11-5 Connective Tissue Disorders and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Table 11-6 Systemic and Localized Infections and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Table 11-7 Tumors and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Table 11-8 Hepatic, Renal, Pulmonary, and Gastrointestinal Disorders and Associated Toenail Conditions Modified from Kosinski MA, Stewart D: Nail changes associated with systemic disease and vascular insufficiency. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 6:295–318, 1989. Used with permission. Heritable traits can influence the appearance of toenails. Many genetic diseases with collagen abnormalities are associated with dermatologic abnormalities and hair and nail disorders (Table 11-9). Table 11-9 Genetic Disorders and Associated Nail Changes DOOR, Deafness, onychoosteodystrophy, osteodystrophy, and mental retardation. Modified from Norton LA: Nail disorders: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2:451–467, 1980. Used with permission. Darier disease (Darier-White disease or keratosis follicularis)148 is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by distal subungual wedge-shaped keratoses, red and white longitudinal striations (Fig. 11-8A, B, and E), splinter hemorrhages, notching of the distal nail plate, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thinning of the nail plate with splintering along the edge. Pachyonychia congenita (Jadassohn-Lewandowsky syndrome),125,152 another autosomal dominant genetic disorder,151,152 is characterized by hypertrophy of the nail plate, with severe thickening and yellowish-brown discoloration of the nail plate (Fig. 11-8C). The extreme thickening is more solid and more regular than with onychogryphosis and is accompanied by palmar and plantar keratoses. The thickening of the nail plate can lead to elevation of the distal nail plate and an incurved and elevated toenail. Tauber et al202 reported a case of pachyonychia congenita and reviewed published reports of this disease. The nail-patella syndrome (onychoosteodysplasia)152,193 is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by a triangular lunula and total atrophy or hemiatrophy of the nail plate (Fig. 11-8D). Other orthopaedic conditions associated with this disease include subluxation or dislocation of the radial head, presence of iliac horns, joint hypermobility, and a subluxated or dislocated hypoplastic patella. Dyskeratosis congenita152 (Zinsser-Cole-Engman syndrome) can be transmitted as an autosomal dominant or X-linked recessive trait and is characterized by ridging and thinning or atrophy of the nail plate. DOOR syndrome152 (deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, and mental retardation) is an autosomal recessive trait characterized by mental retardation and deafness. It may also be associated with absent or atrophic nails and curved fifth digits. Congenital malalignment of the hallux toenail may be transmitted by an autosomal dominant gene of variable expression (Fig. 11-8E). It is characterized by lateral deviation of the long axis of the nail relative to the distal phalanx. Complications of this condition are local, such as perionychium onychocryptosis. In one review, 50% of cases spontaneously improved or resolved; however, the misdirected nail matrix can be rotated surgically.15 Congenital nail abnormalities are errors of development that can produce other anomalies, such as anonychia (absence of the nails) and polyonychia (presence of more than one nail on a digit) or micronychia (small nails) (Fig. 11-9). Trauma to the nail plate may be caused by biomechanical abnormalities as well (see later discussion on subungual hematoma). The second toe can compress the lateral nail fold of the great toe adjacent to the second toe, causing an overgrowth of soft tissue with secondary infection. With more acute trauma, when the nail bed over the distal phalanx is crushed, after the nail bed is repaired, the fragmented nail can be replaced and secured with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond; Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.).93 This material creates a bond between the nail fragments and the skin for 7 to 14 days, when the new nail pushes it off. The material serves as a rigid splint for a fracture as well as a biologic covering to minimize desiccation and hyperkeratinization of the nail matrix. It also prevents the cuticle from adhering to the underlying germinal matrix.190 Similar to nail plate repairs in the hand,34 germinal matrix and nail bed repairs in the foot may be made under loupe magnification, using 7-0 absorbable suture to repair the tissue, with the intention of preventing functional or cosmetic problems. Replacing the nail prevents the eponychium from adhering to the nail bed. It may be held in place with a distal suture or two side sutures (5-0 nylon), which are removed at 7 to 10 days to prevent an epithelialized tract. If the nail is crushed too severely, similar to hand injuries, 0.020-inch silicon sheeting may be placed under the proximal nail fold to protect the nail fold. The surgeon could also remove the nail longitudinally, excise the scar tissue or lesion, and undermine the nail bed all the way to the perionychial tissues to achieve a tension-free closure, as is done for split fingernail injuries.6 A figure-of-eight suture may be used to hold the nail in place.112 1. Create two small slits in the distal aspect of the nail plate. 2. Place the nail plate under the eponychial fold. 3. A 4.0 absorbable or nonabsorble suture is placed into one side of the paronychium distal to proximal. 4. The suture is passed through the notches in the distal nail plate. 5. The suture is placed in the contralateral paronychium from distal to proximal (Fig. 11-10). A germinal matrix graft could also be harvested from adjacent nail tissue, and the nail narrowed as in a Winograd procedure (Fig. 11-11), or harvested from another toe.198 Few studies are available, however, on toenail bed reconstruction. Nonetheless, it makes sense that similar procedures could be used on the toes and the fingers. On the medial aspect of the nail plate, with excessive pronation, hypertrophy of the ungualabia can result in an ingrown toenail. Parrinello et al166 compared the shape of the great toenail with the base of the distal phalanx and found a significant correlation between the shape of the proximal aspect of the nail plate and the shape of the phalangeal base. However, they found no correlation between the shapes of the proximal and distal portions of the nail plate. They concluded that many other factors besides trauma influence the shape of the nail, including constricting footwear, snug-fitting stockings and hosiery, inadequate or inappropriate pedicures, and heritable traits that can lead to incurvation of the nail border, with subsequent inflammation and infection. Split-nail deformities may be treated surgically with nail removal, elliptic nail bed scar removal, and careful elevation of the matrix off the bone with extension of this dissection laterally until the nail matrix can be closed without tension.87 Defects in the nail bed from excisional biopsy can be repaired with a free graft from the lesser toes or with split-thickness, sterile matrix grafts from the adjoining nail matrix.50 Subungual splinters may be removed by sequential thin, sharp filings of the nail until the splinter is exposed along its entire length. This allows complete splinter removal without having to remove the entire nail.188 Avulsion of the nail plate can leave the nail bed open and possibly injured (Fig. 11-12). As the nail bed scars, the surface may become irregular, resulting in a deformed new nail or arrest of new nail regeneration. Wounds into the germinal matrix may result in a longitudinal groove in the nail plate or a split nail. To minimize these possible outcomes, keep the proximal fold patent with foil or the injured nail plate by placing it back under the proximal fold after fracture irrigation and nail bed repair. If the proximal portion of the germinal matrix under the proximal fold is intact, a tear in the distal germinal matrix will not necessarily prevent regrowth of the nail but may cause deformity with time. Matrix contusions may also lead to loss of nail growth. Hematomas may be evacuated to reduce pain and pressure depending on size. In treating nail crush injuries, devitalized tissues should be excised. For fractures of the terminal phalanx, large bone fragments can be splinted or sutured. The nail often serves as a splint once the soft tissues are repaired. Damage of the matrix and periosteum requires repair with fine (6-0 or smaller) suture (Fig. 11-12). Tumors of the soft tissue adjacent to the toenails or involving the nail unit itself can be benign or malignant (Box 11-6). Periungual and subungual warts (verrucae) are common soft tissue growths (Fig. 11-13). Fibromas181 and fibrokeratomas can result from trauma to the toes, with consequent nodule formation impinging on the nail plate. These benign connective tissue lesions can also develop beneath the nail plate itself and cause elevation and deformity. Pressure on the nail matrix can create a longitudinal defect in the nail plate as well. A periungual fibroma or angiofibroma (see Fig. 11-13F) may be the first evidence of tuberous sclerosis or ectodermal dysplasia. In general, fibromas respond readily to excision or cauterization. Glomus tumors, pyogenic granulomas, and keratoacanthomas must all be considered in the differential diagnosis. A glomus tumor is most commonly encountered on the acral portions of the extremities. This lesion is often in the subungual area and consists of a reddish purple nodule measuring only a few millimeters in diameter. It is tender and gives rise to severe paroxysmal pain. Glomus tumors rarely ulcerate or bleed, and excision usually results in a cure, although subungual lesions are more difficult to eradicate. They are almost universally benign; however, because of symptoms and malignant potential, diagnosis and treatment is essential.138 The differential diagnosis includes melanoblastoma, melanoma, neuroma, chronic perionychium, gout, arthritis, foreign body granuloma, and Kaposi sarcoma. The glomus tumor appears to be a cutaneous arteriovenous anastomosis arising from a highly vascular compilation of epithelioid cells and glomus cells known as a glomus body.138 This thermoregulatory structure, found densely within the fingers and toes, is responsible for temperature, vascular regulation, and sensation; hence it tends to give the patient cold insensitivity.105,138 The only effective treatment for a glomus tumor is complete surgical excision.138 Excision with negative margins results in adequate diagnosis and treatment. If malignant features are present, wide excision is needed, with close follow-up for development of metastasis.138 Previously, it was necessary to remove the nail, incise the nail matrix, remove the tumor, and repair the nail bed. A study of seven cases,105 however, demonstrated that creating an L-shaped incision, 5 mm distal and 5 mm medial or lateral to the nail, and lifting off the entire vascular flap allowed removal of the tumor (Fig. 11-14A-C). The flap was then sutured back to its origin after hemostasis.105 There were no recurrences or nail irregularities. This technique might lend itself to other subungual operations as well, such as treatment of subungual exostosis. This approach has been used by others and is recommended for all noninvasive space-occupying subungual lesions, regardless of type.180 Radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans may show small cortical abnormalities in the distal phalanx. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine the precise location of the tumor and may show a well-circumscribed highly vascular mass (Fig. 11-14D and E).138 Pahwa161 described a “trap door” technique used for glomus tumor excision in which medial and lateral slits were cut in the proximal nail fold in line with the gutters. The distal plate is then carefully freed from the underlying bed and elevated from it distally, with the proximal plate and proximal fold acting as a hinge. The tumor can then be excised and then the nail plate and nail fold sutured back into position. Another type of glomus tumor, which is different histologically and is characterized by multiple painless hemangiomas, often has an autosomal dominant familial pattern.43,138 These multiple lesions are usually asymptomatic. A subungual exostosis is a benign bony growth typically occurring on the dorsomedial aspect of the distal phalanx tuft (Fig. 11-15A-D).37,39,52,142,145 Originally described by Dupuytren in 1817, subungual exostosis has a predilection for the hallux, although occasionally it develops in the lesser toes. A subungual exostosis typically has a moderate growth rate, resulting in growth that rarely exceeds 0.5 cm. Osteochondroma characteristically occurs on the dorsal aspect of the phalanx in a juxtaepiphyseal region, whereas exostosis may be closer to the tip of the phalanx (Table 11-10),129,142,207 Osteochondroma occurs more often in adolescent boys than girls (2 : 1 ratio). In contrast, subungual exostosis is seen more commonly in young adults aged 20 to 40 years. Ippolito et al108 found that subungual exostoses occurred more often in the female population (2 : 1 ratio), whereas Miller-Breslow and Dorfman142 reported an equal distribution between male and female patients. Table 11-10 Distinguishing Features of Subungual Exostosis and Subungual Osteochondroma Modified from Norton LA: Nail disorders: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2:457–467, 1980. Used with permission. Osteochondroma is attributed to a congenital cause, although the patient may recall a traumatic event that brings a formally asymptomatic lesion to their attention.210 Vazquez-Flores et al210 noted in a review of 27 cases of subungual osteochondroma, trauma was recalled by 40.7% of the patients. The cause of subungual exostosis is thought to be traumatic, infectious, or from chronic irritation.73,145,155,207 Fikry et al73 found a history of trauma or repetitive microtrauma in 21 of 28 cases of exostosis. In distinguishing between subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma, the histologic characterization of the cartilage cap is diagnostic. In a subungual osteochondroma, a hyaline cartilage cap overlies a trabeculated bony pattern. However, subungual exostosis has a fibrocartilaginous cap that is a reactive fibrous growth with cartilage metaplasia.142 Jahss109 noted that a subungual exostosis is characterized histologically as chronic fibrosis caused by irritation. A trabecular bony pattern connecting with the distal phalanx can underlie the fibrocartilaginous cap.142 Reporting on 21 cases of subungual exostosis, Ippolito et al108 noted that 12 patients were athletes involved in activities such as dancing, gymnastics, or football. It is believed that increased pressure against the dorsal aspect of the nail plate from a constricting toe box can cause irritation that leads to the development of a subungual exostosis. The connection between a specific traumatic incident and the subsequent development of a subungual exostosis can also explain the increased incidence of this abnormality in athletes. Many patients describe pain that is aggravated by activities such as running or walking and is most likely from the pressure of an expanding lesion against the toe box. A subungual exostosis can be misdiagnosed or confused with other toenail abnormalities.108 Elevation of the nail plate (Fig. 11-16A) and discoloration can resemble chronic onychomycosis or a subungual hematoma. Chinn and Jenkin39 reported two cases of patients with pain in the proximal nail groove who had undergone an unsuccessful surgical matrixectomy and who later received a diagnosis of subungual exostosis. The differential diagnosis includes subungual verruca, pyogenic granuloma, glomus tumor, keratoacanthoma, subungual nevus, and epidermoid inclusion cyst as well as malignant lesions, such as carcinoma of the nail bed and subungual melanoma.

Toenail Abnormalities

Anatomy

Dermatologic and systemic diseases

Dermatologic and systemic diseases

Congenital and genetic nail disorders

Congenital and genetic nail disorders

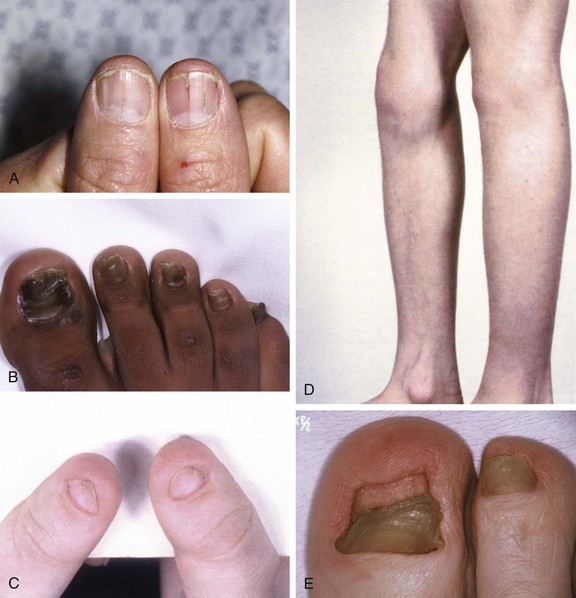

Common nail abnormalities and onychodystrophies (Fig. 11-3A-E)

Common nail abnormalities and onychodystrophies (Fig. 11-3A-E)

Dermatologic and Systemic Nail Disorders

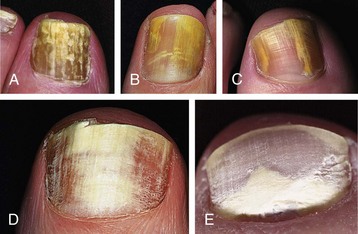

Psoriasis

Stippling or geographic pitting (tiny, often grooved depressions in the surface of the nail plate) (Fig. 11-4), which is not unique to psoriasis and is seen in alopecia areata

Stippling or geographic pitting (tiny, often grooved depressions in the surface of the nail plate) (Fig. 11-4), which is not unique to psoriasis and is seen in alopecia areata

Onycholysis, especially laterally and distally, sometimes with yellowing and opacity of the nail plate, which separates and then detaches from the nail bed (Fig. 11-4B-D)

Onycholysis, especially laterally and distally, sometimes with yellowing and opacity of the nail plate, which separates and then detaches from the nail bed (Fig. 11-4B-D)

Staining of the nail (oil spot lesions) (Fig. 11-4B and C)

Staining of the nail (oil spot lesions) (Fig. 11-4B and C)

Subungual keratosis (Fig. 11-4E)

Subungual keratosis (Fig. 11-4E)

Pyodermas

Systemic Diseases

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Arterial emboli

Splinter hemorrhages

Arteriosclerosis obliterans

Leukonychia partialis

Bacterial endocarditis

Clubbing, splinter hemorrhages

Hypertension

Splinter hemorrhages

Ischemia

Onycholysis, pterygium

Mitral stenosis

Splinter hemorrhages

Myocardial infarction

Mees lines, yellow nail syndrome

Vasculitis

Splinter hemorrhages

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Cryoglobulinemia

Splinter hemorrhages

Hemochromatosis

Brittleness, koilonychia, leukonychia, longitudinal striations, splinter hemorrhages

Hemophilia

Ingrown toenails,98 pyogenic granulomata

Histiocytosis X

Onycholysis, pitting, splinter hemorrhages

Hodgkin disease

Leukonychia partialis, Mees lines, yellow nail syndrome

Hypochromic anemia

Koilonychia

Idiopathic hemochromatosis

Brittleness, koilonychia, longitudinal striations, splinter hemorrhages

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease

Splinter hemorrhages, telangiectasia

Polycythemia rubra vera

Clubbing, koilonychia

Porphyria

Onycholysis

Sickle cell anemia

Leukonychia, Mees lines, splinter hemorrhages

Thrombocytopenia

Splinter hemorrhages

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Addison disease

Brown bands, diffuse hyperpigmentation, leukonychia, yellow nail syndrome, longitudinal pigmented deep yellow bands

Diabetes mellitus

Beau lines, koilonychia, leukonychia, onychauxis, onychomadesis, paronychia, pitting of nail plate, proximal nail bed telangiectasia, pterygium, splinter hemorrhages, yellow nail syndrome

Hyperthyroidism

Clubbing, increased nail growth, onycholysis, splinter hemorrhages, yellow nail syndrome

Hypothyroidism

Onycholysis, koilonychia, yellow nail syndrome

Thyroiditis

Yellow nail syndrome

Thyrotoxicosis

Koilonychia, onychomadesis, splinter hemorrhages, yellow nail syndrome

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Alopecia areata

Leukonychia partialis, nail pitting

Atopic dermatitis/eczema

Onycholysis, onychorrhexis

Lichen planus169,174

Atrophy of nail plate, onycholysis, onychorrhexis, pterygium

Psoriasis

Beau lines, leukonychia, Mees lines, nail pitting, onycholysis, splinter hemorrhages

Raynaud syndrome

Koilonychia, yellow nail syndrome

Reiter syndrome

Onycholysis, nail pitting

Rheumatoid arthritis

Splinter hemorrhages, yellow nail syndrome

Scleroderma (62% of patients)189

Absent lunula, koilonychia, leukonychia, onycholysis, onychorrhexis, pterygium

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Clubbing, hyperpigmented periungual tissue, nail pitting, onycholysis, subungual petechiae, yellow nail syndrome

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Bacterial endocarditis

Clubbing, splinter hemorrhages

Hansen disease

Loss of lunula, nail plate dystrophy, onychogryphosis, onychauxis, onycholysis, onychodesis, onychomadesis, onychorrhexis

Malaria

Grayish nail bed, leukonychia

Measles

Onychomadesis

Recurrent cellulitis

Yellow nail syndrome

Scarlet fever

Onychomadesis

Syphilis

Koilonychia, leukonychia partialis, onychauxis, onychia, onycholysis, onychomadesis, onychorrhexis, paronychia

Trichinosis

Splinter hemorrhages, leukonychia

Tuberculosis

Leukonychia partialis, yellow nail syndrome

Typhoid fever

Leukonychia, Mees lines

Yaws and pinta

Hypopigmentation, nail atrophy, onychia, onychauxis, paronychia, pterygium

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Breast carcinoma

Yellow nail syndrome

Bronchogenic carcinoma

Clubbing, Muehrcke lines, onycholysis

Hodgkin disease

Leukonychia partialis, Mees lines, yellow nail syndrome

Laryngeal carcinoma

Yellow nail syndrome

Metastatic malignant melanoma

Clubbing, yellow nail syndrome

Multiple myeloma

Onycholysis

Disease

Pathologic Changes

Hepatic

Chronic hepatitis

Half-and-half nails, leukonychia

Cirrrhosis

Clubbing, Muehrcke lines, splinter hemorrhages, Terry nails

Renal

Nephritis

Leukonychia

Nephrotic syndrome

Half-and-half nails, Muehrcke lines, yellow nail syndrome

Renal failure

Brown lunula, half-and-half nails, Mees lines

Pulmonary

Asthma

Yellow nail syndrome

Bronchiectasis

Clubbing, inflammation of nail fold and nail bed, onychauxis, onycholysis, yellow nail syndrome

Chronic bronchitis

Clubbing, yellow nail syndrome

Interstitial pneumonia

Clubbing, yellow nail syndrome

Pleural effusion

Clubbing, onycholysis, yellow nail syndrome, leukonychia, Mees lines

Pneumonia

Clubbing, yellow nail syndrome

Pulmonary fibrosis

Cyanosis, multiple paronychia, nail pitting

Pulmonary tuberculosis

Onychauxis

Gastrointestinal

Peptic ulcer disease

Splinter hemorrhages

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

Koilonychia

Postgastrectomy syndrome

Koilonychia

Regional enteritis

Clubbing

Ulcerative colitis

Clubbing, leukonychia

Genetic Disorders with Nail Changes

Disease or Syndrome

Genetic Inheritance

Pathologic Nail Findings

Darier disease

Autosomal dominant

Longitudinal red-and-white striations, atrophy or hypertrophy of nail plate, splinter hemorrhages, distal subungual wedge-shaped keratoses

Pachyonychia congenita

Autosomal dominant

Massive hypertrophy of nail plates, brown or yellow discoloration

Nail-patella syndrome

Autosomal dominant

Atrophy or hemiatrophy of nail, triangular-shaped lunula

Dyskeratosis congenita

X-linked recessive or autosomal dominant

Atrophy of nail plate, ridging, fusion of proximal nail fold

DOOR syndrome

Autosomal recessive

Anonychia or atrophic nails

Frizzled D 6 caused isolated nail dystrophy78

Autosomal recessive

Nail dysplasia, hyponychia, onycholysis, onychauxis

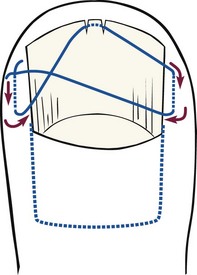

Trauma

Transeverse Figure-of-Eight Suture for Securing the Toenail

Surgical Technique

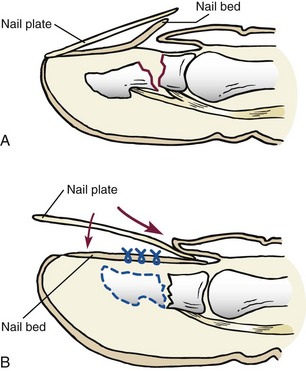

Crush Injuries to the Nail

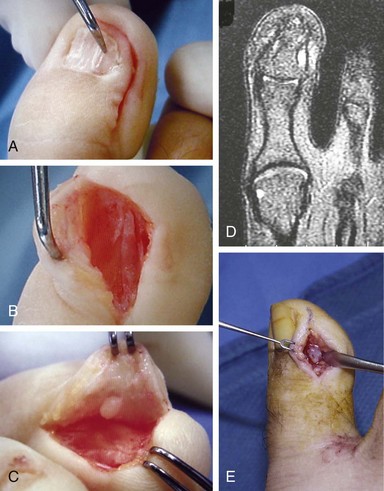

Tumors

Glomus Tumor

Subungual Exostosis and Osteochondroma

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Toenail Abnormalities