2.8 Therapy for Lymphedema

Definition of Lymphedema

Definition of Lymphedema

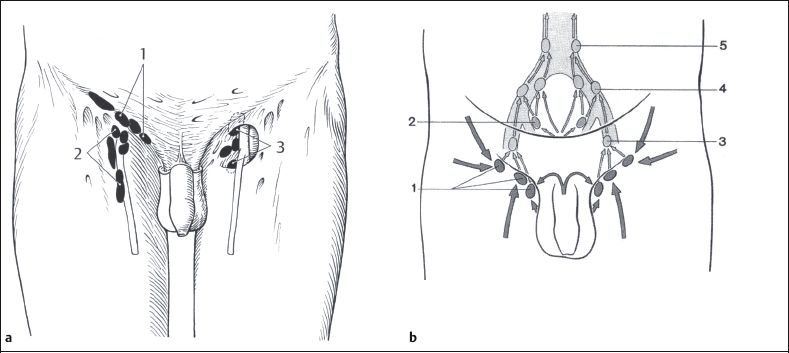

Lymphedema is a chronic condition, characterized by protein-rich swelling in the interstitium, which can occur anywhere in the body with the exception of the central nervous system and cornea [Foeldi et al. 2003]. Lymphedema is usually seen in the subcutaneous tissues of the arms or legs, or both. The swelling is a result of the body’s inability to transport accumulated fluid along lymph pathways and is usually caused by a mechanical insufficiency of the lymphatic system. If lymphedema occurs in the genitals, it is usually seen in combination with lower-extremity involvement [Foeldi et al. 2003]. Because of the close proximity of the genitals, lymphedema may be concurrent in the abdominal tissues (Figs. 2.102, 2.103). It may occur in men and women, and in primary (at birth and/or hereditary) or secondary (acquired) forms of lymphedema. There have been few reports regarding the number of people affected by genital lymphedema, but it is estimated that 10–20% of gynecological oncology surgery procedures and radiation therapy procedures result in genital lymphedema [Cheville 2003]. Signs and symptoms of lymphedema may include:

- Swelling usually with pitting

- Cellulitis (bacterial skin infection)*

- Numbness and tingling (increasing edema pressure)

- Fibrotic changes in the skin

- A sensation of heaviness in the affected tissues

- Papillomas (lymph blisters or cysts)*

- Tightness of skin

- Persistent genital yeast infections*

- Lymphorrhea (weeping)*

- Pain (secondary to increased edema pressure)

The signs and symptoms marked with asterisks are common in genital lymphedema because of the moist environment typical of the anatomy.

Primary functions of a healthy lymph system [Foeldi et al. 2003]:

- To produce and deliver lymphocytes to protect the body from infection and diseases (immune response).

- To provide fluid transport, leading to chemically balanced interstitial fluid and normal blood volume.

Components of the lymph system

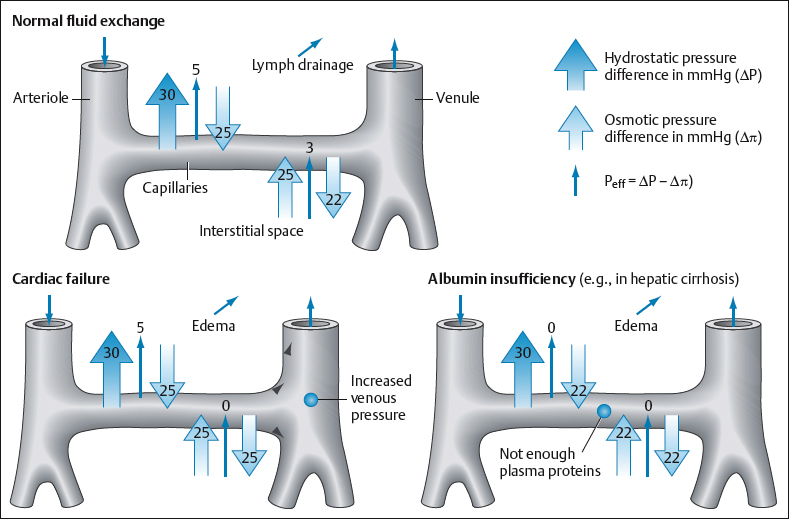

- The lymph vessels, beginning with smaller-lumen vessels and progressing to deeper and larger-lumen vessels, manage protein diffusion and reabsorption [Starling’s equilibrium] [Foeldi et al. 2003, Wittlinger and Wittlinger 2003] (Fig. 2.104). Medium-sized vessels, known as collectors, have one-way valves that pump lymph fluid toward the lymph nodes for filtering.

- The lymph nodes are organs that filter waste and regulate the protein concentration in lymph fluid. Other lymph organs include the thymus and spleen.

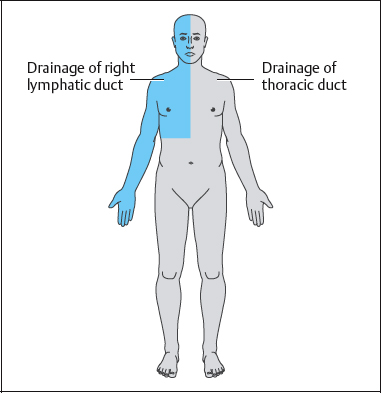

- The lymphatic trunks constitute the deeper larger lymph vessels. They empty into the thoracic duct, which receives three-quarters of the lymph processed by the body, and the right lymphatic duct, which receives the remaining quarter of the lymph (Fig. 2.105). These two large trunks deliver lymph to the venous angles for removal of processed waste products via the kidneys. The thoracic duct empties into the left subclavian vein, and the right lymphatic duct empties into the right subclavian vein. In a 24-h period, approximately 2–4 L of lymph flows through the lymph vessels and ducts to the subclavian veins. There is a large functional transport capacity reserve of about 30% in the lymphatic system, which allows most individuals with lymphatic system damage to escape developing lymphedema. Risks include factors that cause increased circulation, such as extreme heat, trauma, and excessive exercise. Due to its effects on the sympathetic nervous system, stress is an additional risk factor for patients who have lymphedema [Foeldi et al. 2003, Wittlinger and Wittlinger 2003].

Primary versus Secondary Lymphedema

Primary versus Secondary Lymphedema

Primary lymphedema is a rare form of the disease that is usually the result of lymphnode or lymphvessel hypoplasia, although other dysplasias may be present. The lower extremities are more often involved than other body parts. While the onset of primary lymphedema usually occurs around age 17 (lymphedema praecox), it may be present at birth (Milroys’) or may present after the age of 35 (lymphedema tarda). Eighty-seven percent of cases occur in females [Casley-Smith 1995, Kelly 2002].

Secondary lymphedema is acquired and is much more common than the primary form. The most common etiologies of secondary lymphedema include:

- Operations for cancer of the breast and pelvic regions often result in disruption of lymph flow, caused by damage to the lymph nodes and vessels in the axillary and inguinal areas. Disruption of the inguinal lymph nodes may cause genital lymphedema. Other forms of surgery, depending on the extent and location of the operation, may cause or intensify lymphedema—for example, multiple plastic, venous, and pelvic operations conducted may cause sufficient scarring of lymph structures to reduce the transport capacity in the affected region.

- Radiotherapy causes fibrosis of the affected tissues, thereby reducing the avenues of transport for lymph as it moves through the local lymph vessels and nodes. Fifty percent of patients receiving radiotherapy develop lymphedema [Casley-Smith and Casley-Smith 1997].

- Filariasis is a condition caused by invasion of the nematode worm into lymph vessels via mosquito bites. It is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, but rarely seen in Western countries. The worm larvae reproduce and die in the lymph vessels, causing blockage. Secondary bacterial or fungal infections are common; if they are not treated with antibiotics during the early stages of the disease, infected people usually develop lymphostatic elephantiasis, a grossly disfiguring chronic condition [Weissleder and Schuchardt 1997, Kelly 2002, Foeldi et al. 2003].

- Tumor growth invading lymph nodes may cause lymphedema.

- Infection may increase edema in an already overloaded lymph system, due to increased local blood flow and capillary permeability, resulting in tissue fibrosis and destruction.

- Chronic venous insufficiency may cause lymphedema-like symptoms, due to a fluid overload caused by diseased veins.

- Applying a tourniquet to a body part for an extended period of time, or wearing extremely tight clothing, can cause artificial or self-induced lymphedema [Klose and Thoma 2004]. Genital lymphedema may occur if a tourniquet effect is present around the abdomen or upper thigh in persons who are at high risk for developing lymphedema. Male patients with diabetes mellitus may be inclined to place a band around the base of their penis to achieve adequate erection for sexual function. This can also cause lymphedema due to a tourniquet effect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree