The Use of Free Flaps in Upper Extremity Reconstruction/ Anterolateral Thigh Flap

Lawrence Lin

Samir Mardini

Steven L. Moran

Indications/Contraindications

Soft tissue deficiencies within the upper extremity are common following trauma, burns, infection, and tumor extirpation. The coverage of such defects can usually be accomplished with the use of pedicled flaps or local rotational flaps. However, when defects are very large or encompass multiple structures including nerve, bone, or muscle, the use of composite free tissue transfer provides a reliable and single stage means of reconstructing complex defects.

The benefits of free tissue transfer within the upper extremity include the transfer of additional vascularized tissue to the injured area, the ability to carry vascularized nerve, bone, skin, and muscle to the injured area in one procedure, and the avoidance of any additional functional deficits to the injured limb which may be incurred with the use of a local or pedicled flap. Free flaps are not tethered at one end, as is the cases for pedicled flaps, and this allows for more freedom in flap positioning and insetting. More recent fasciocutaneous and perforator flaps also allow for primary closure of donor sites with minimal sacrifice of donor site muscle. With current microsurgical techniques, free flap loss rates are between 1% and 4% for cases requiring elective free tissue reconstruction. Finally, the upper extremity is particularly suited for free tissue transfer as the majority of recipient blood vessels utilized for anastomosis are located close to the skin, and are of relatively large caliber.

Major indications for free tissue transfer are: (a) primary coverage of large traumatic wounds with exposed bone, joint, and tendons or hardware, (b) coverage of complex composite defects requiring bone and soft tissue replacement, (c) coverage of soft tissue deficits resulting from release of contractures or scarring from previous trauma, and (d) significant burns.

There are few absolute contraindications for free flap transfer and in many cases free tissue transfer may be the only option for upper limb salvage following significant soft tissue loss. Despite this, relative contraindications to free tissue transfer include a history of a hypercoagulable state, history of recent upper extremity DVT, and evidence of ongoing infection with the traumatic defect. Other contraindications would include inadequate recipient vessels for flap anastomosis. Disregarding

technical error, the status of the recipient vessel used for flap anastomosis may play the greatest role in flap failure; recipient vessels within the zone of injury are prone to postoperative and intraoperative thrombosis. Recipient vessels for microvascular transfer should ideally be located out of the zone of injury, radiation, or infection. In rare cases, arterial venous fistulas may be created proximally within the upper extremity or axilla using the cephalic or saphenous vein. These fistulas can be brought into the zone of injury and divided to provide adequate inflow and outflow for free tissue transfer.

technical error, the status of the recipient vessel used for flap anastomosis may play the greatest role in flap failure; recipient vessels within the zone of injury are prone to postoperative and intraoperative thrombosis. Recipient vessels for microvascular transfer should ideally be located out of the zone of injury, radiation, or infection. In rare cases, arterial venous fistulas may be created proximally within the upper extremity or axilla using the cephalic or saphenous vein. These fistulas can be brought into the zone of injury and divided to provide adequate inflow and outflow for free tissue transfer.

Specific Indication for the Anterolateral Thigh Flap

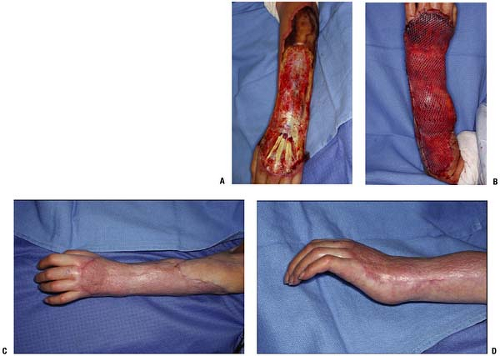

There are many choices for free flap coverage of the upper extremity. The scapular, parascapular, latissimus dorsi myocutaneous, and lateral arm flap have long been favorites of surgeons for reconstruction of traumatic upper extremity injuries. Many of these flaps will be described in later chapters of this text. If joints are to be crossed, fasciocutaneous flaps are much preferred as muscle flaps can undergo atrophy and restrict flexion and extension across joints or fingers (Fig. 18-1).

Classic cutaneous free flaps, such as the radial forearm flap, lateral arm flap, and scapular flap, have limitations in size, donor site morbidity, and overall thickness. Musculocutaneous flaps such as the latissimus dorsi and rectus abdominus flaps result in functional loss and donor site morbidity including, particularly in the abdomen, potential hernia formation. In addition, in coverage of joint surfaces, muscle flaps tend to undergo fibrosis and atrophy over time, which may limit muscle excursion, particularly when placed over the elbow or dorsum of the hand. Muscle is still indicated for those circumstances involving osteomyelitis or significant soft tissue contamination. More recently, chimeric flaps have been harvested to include both muscle and a large component of skin, providing the ideal coverage for many complex defects in the upper extremity.

In recent years, the anterolateral thigh flap has become the major flap in reconstructive microsurgery, including head and neck defects and extremity wounds. It has replaced many other flaps. The skin overlying the anterior thigh region has relatively constant anatomy with the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery (LFCA), giving rise to either pure muscular (musculocutaneous) or subcutaneous (septocutaneous) perforators that supply the area. Based on their experience with over 1,500 anterolateral thigh flaps for various anatomic defects including the upper extremity, Chen et al determined that 12% were based on direct septocutaneous perforators, and 88% were based on musculocutaneous perforators. Variations in perforator anatomy can exist, which include absence of skin perforator, perforators which are too small for elevation, a perforator artery which does not run with the vein, and perforator arteries that have no accompanying vein. These anatomical variations are rare, accounting for 2% of cases, however they need to be noted by the surgeon. As proposed by Chen, an algorithm for managing anatomical variations begins with attempting to identify a more proximal perforator in the upper thigh, usually arising from the transverse branch of the LFCA, and harvesting the flap based on this perforator. Alternatively, an anteromedial thigh flap may be raised or the vastus lateralis may be taken as a musculocutaneous flap. Finally, exploration can be performed on the contralateral side as the anatomy may be different.

The anterolateral thigh flap serves as the ideal flap for upper extremity coverage due to its many considerable advantages. The flap provides a long pedicle (up to 16 cm) with suitable vessel diameters; the arterial pedicle can measure up to 2.5 mm and the two venae comitantes can measure up to 3 mm in diameter. It is also a versatile flap with the ability to incorporate different tissue components with large amounts of skin, as the flap can be harvested as a cutaneous, fasciocutaneous, or musculocutaneous flap with vastus lateralis. In addition, based on the supply of the LFCA system, a chimeric flap incorporating the rectus femoris or tensor fascia lata can be raised to cover extensive, complex defects. The flap may be harvested as a sensate flap by including the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve or as a flow-through flap in cases of significant arterial trauma. Inclusion of thigh fascia with the flap allows its use as an interposition graft for tendon reconstruction. The thickness of the flap may be debulked primarily, optimizing the match of donor tissue for the upper extremity. Ordinary skin flaps can sometimes produce bulkiness with poor aesthetics. Thick skin paddles, such as with parascapular flaps, may interfere with motor function and flexion of the metacarpal phalangeal joints or inter-phalangeal joints. Flaps as thin as 3 mm to 5 mm have been harvested for tendon coverage. The donor site results in minimal morbidity with most sites able to be closed primarily, resulting in a linear scar and absence of any long term leg dysfunction. Lastly, its anatomic location allows for a two-team approach for flap elevation and recipient site preparation, saving considerable operative time.

Anterolateral Thigh Flap for Upper Extremity Reconstruction

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative requirements for flap consideration begin with the preparation of a clean wound bed. Radical debridement of all necrotic tissue is the most important component of a successful reconstruction. Tissue considered to be of marginal viability should be debrided early rather than performing multiple dressing changes or utilizing vacuum-assisted therapy in the hopes of rescuing traumatized tissue; such measures can lead to delayed definitive surgical reconstruction, perpetuate the inflammatory component of wound healing, perpetuate distal edema, and result in hand and limb stiffness. If the surgeon can guarantee a clean wound bed, free of any necrotic material, immediate flap coverage may be attempted in cases of acute trauma. We have found that most high energy traumatic injuries and agricultural accidents require at least one to two surgical debridements prior to definitive wound closure. Wound debridements in these cases are performed in conjunction with wound cultures for bacteria and fungal species. The ideal timing for upper limb free tissue reconstruction has been debated within the literature but should be within 72 to 96 hours of injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree