Chapter 7 T51 Sitting: pelvic twist (swivel chair) test T52 Standing: pelvic side-shift test T53 Standing: one arm wall push test T54 4 point: one arm lift test T55 Side-lying: lateral arm lift test Thoracic/rib respiration control The thoracic spine has been the focus of little research or review attention compared to the lumbar and cervical spine. This may partly be due to the lower frequency of thoracic spinal pain syndrome and partly because the thoracic region is well stabilised by the rib cage and rib articulations to the thoracic vertebrae (Watkins et al 2005). Almost all of the research and review literature available that is related to the thoracic spine is based on anatomical and biomechanical analysis of osteoligamentous and myofascial influences on articular function (Edmondston & Singer 1997; Maitland et al 2005). There is a lack of research and analysis of neurophysiological motor control changes associated with pain and dysfunction in the thorax. The diagnosis of the site and direction of UCM in the thoracic spine can be identified in terms of the site (being thoracic spine) and the direction of flexion, extension, rotation and respiratory movement (Table 7.1). The site and direction of UCM at the thoracic spine can link with different clinical presentations, and postures and activities which may aggravate symptoms. The typical assessment findings in the thoracic spine are identified in Table 7.2. Table 7.2 The site and direction of UCM at the thoracic spine linked with different clinical presentations • Lumbopelvic restriction of flexion – a lumbopelvic flexion restriction may contribute to compensatory increases in thoracic flexion range. This is confirmed with manual segmental assessment (e.g. Maitland PPIVMs or PAIVMs) of the lumbopelvic joints. There may also be a loss of lumbar-dorsal fascia extensibility if a lordotic posture is exaggerated. • Cervical restriction of flexion – a cervical flexion restriction may contribute to compensatory increases in thoracic flexion range. This is not usually associated with articular restrictions of flexion. However, a chin poke neck posture may have an increased cervical lordosis and a loss of extensibility of the posterior cervical fascias and the ligamentum nuchae. • Scapular restriction of protraction – recruitment overactivity or postural change may result in a loss of extensibility of the rhomboids. A subsequent myofascial restriction of scapular protraction may also contribute to compensatory increases in thoracic flexion range. • Thoracic flexion – the thoracic spine may initiate the movement into flexion and contribute more to producing forward bending while the lumbar spine and hip contributions start later and contribute less. At the limit of forward bending, excessive or hypermobile range of thoracic flexion may be observed. During the return to neutral the thoracic flexion persists and presents as an increased thoracic kyphosis. The person stands with the back of the pelvis, the upper thoracic spine and the back of the head resting against a wall with the shoulders and arms relaxed. The heels are positioned about 20 cm in front of the wall with the feet at least shoulder width apart and with the knees slightly flexed (hip flexors unloaded and wide base of support) (Figure 7.1). Then, keeping the thoracic spine and head stationary on the wall, the person is instructed to roll the pelvis backwards into posterior tilt to flatten the lumbar spine against the wall. The lumbar lordosis should reverse so that the whole lumbar spine is in full contact with the wall (Figure 7.2). There should be no flexion of the thorax, head or shoulders off the wall. If control is poor, retraining is best started by allowing both the lumbar and thoracic spines to start in flexion, and then reverse the dysfunction by unrolling the thoracic spine back up the wall into extension. The person stands with the heels at least shoulder width apart and about 20 cm in front of a wall with the knees slightly flexed (hip flexors unloaded and wide base of support). Rest the pelvis against the wall and allow the whole spine to slump forwards into flexion, but roll the pelvis backwards into posterior tilt and flatten the lumbar spine against the wall (Figure 7.3). Once the pelvis and lumbar spine are in contact with the wall, slowly lift the head and chest to unroll the thoracic spine back up the wall (Figure 7.4). Only move as far as the thoracic extensor muscles can extend the thoracic spine while holding the lumbopelvic region flat on the wall. The person should self-monitor the control of thoracic flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T42.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T42.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining Once segmental unrolling and control of the thoracic flexion improves, the exercise can return to the original start position. The person stands with the back of the pelvis, the upper thoracic spine and the back of the head resting against a wall. Then, keeping the thoracic spine and head stationary on the wall, the person rolls the pelvis into posterior tilt to flatten the lumbar spine against the wall. They should only roll the pelvis into posterior tilt as far as the head and thoracic spine can stay on the wall (Figure 7.5). At the point in range that the head and thoracic spine begin to flex off the wall, the movement should stop. The person should have the ability to actively hang the head forwards towards the sternum (flexing the cervical spine) while controlling the thoracic spine and preventing thoracic flexion. The person sits tall with the feet off the floor and with the spine and head positioned in the neutral. Position the head directly over the shoulders without chin poke (Figure 7.6). Without letting the thoracic spine or shoulders move, lower the head forwards towards the sternum. Do not allow the sternum or shoulders to drop forwards. This is independent cervical flexion. Ideally, the person should have the ability to keep the thoracic spine neutral and prevent thoracic flexion while independently flexing the cervical spine region through full flexion so that the chin is within 2–3 cm of the upper sternum (Figure 7.7). The thoracic spine and the back of the head are supported upright against a wall (Figure 7.8). The person should monitor the control of thoracic flexion by palpating the sternum or clavicles. Any forward or lowering movement of the sternum or clavicles indicates uncontrolled thoracic flexion. The person is instructed to slowly allow the head to flex forwards off the wall. Only allow the head to hang forwards as far as there is no thoracic flexion (monitored by the hand palpating the sternum). Using feedback from palpating the sternum, the person is trained to control and prevent thoracic flexion and perform independent lower cervical flexion (Figure 7.9). The person should self-monitor the control of thoracic flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T43.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T43.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining The person is then instructed to make the spine as tall or as long as possible to position the normal curves in an elongated ‘S’. Position the head directly over the shoulders without chin poke (Figure 7.10). Then, without letting the thoracic spine flex (sternum does not lower or move forwards), actively roll the pelvis backwards (tuck the tail under the pelvis) into full available posterior pelvic tilt. The person is required to produce the same range of posterior pelvic tilt that the therapist identified with passive assessment. Ideally, the person should have the ability to dissociate the thoracic spine from posterior pelvic tilt as evidenced by the ability to prevent thoracic flexion while independently rolling the pelvis backwards (Figure 7.11). There must be no movement into thoracic flexion. There should be no provocation of any symptoms under posterior tilt (flexion) load, so long as the thoracic flexion UCM can be controlled. Retraining is best started by supporting the thoracic spine against a wall for increased thoracic support and feedback and posterior tilting the pelvis through reduced range. The person stands with the back of the pelvis, the upper thoracic spine and the back of the head resting against a wall with the shoulders and arms relaxed. The pelvis is positioned in anterior tilt to start the training. This can also be performed with the person sitting on a low stool with the feet on the floor and the thoracic spine and head resting against a wall. Then, keeping the thoracic spine and head stationary on the wall, the person is instructed to roll the pelvis backwards into posterior pelvic tilt (Figure 7.12). It may be useful to visualise tucking an imaginary tail under the pelvis. Another visualisation cue is to visualise the pelvis as a bucket full of water and the thorax as the handle of the bucket. The aim is to visualise the ability to tip water out the back of the bucket but not allow the handle to swing forwards into thoracic flexion. If control is poor, it is also recommended that the person use self-palpation to monitor the correct performance of the exercise. Monitor the control of thoracic flexion by placing one hand on the sternum or clavicles. Monitor lumbopelvic motion by placing the other hand on the sacrum (Figure 7.13). Without letting the thoracic spine flex (sternum does not lower or move forwards) actively roll the pelvis backwards (tuck the tail under the pelvis) into full available posterior pelvic tilt. Using feedback from palpating the sternum, the person is trained to control and prevent thoracic flexion and perform independent posterior pelvic tilt. Only allow posterior pelvic tilt (tail tuck) as far as there is no thoracic flexion (monitored by the hand palpating the sternum). There must be no UCM into thoracic flexion. There should be no provocation of any symptoms under flexion load, so long as the thoracic flexion UCM can be controlled. The person should self-monitor the control of thoracic flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T44.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T44.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining 1. First, actively posterior tilt the pelvis to end range, and then extend the thoracic spine as far as possible without losing the posterior tilt (Figure 7.14). 2. The reverse order of this same pattern may also be used. That is, first, actively extend the thoracic spine as far as possible and then posteriorly tilt the pelvis (Figure 7.15). The person should have the ability to actively reach forwards with both arms into full scapular protraction while controlling and preventing thoracic flexion. The person sits tall with the feet off the floor. The person is then instructed to sit upright with the spine in its neutral normal curves and the head directly over the shoulders without chin poke. Both arms are held at 90° of shoulder flexion, with the scapulae relaxed in a neutral mid-position (Figure 7.16). Then, without letting the thoracic spine flex (sternum does not lower or move forwards) or the head to move forwards, actively reach forwards with both hands into full available scapular protraction. Ideally, the person should have the ability to dissociate the thoracic spine from scapular protraction as evidenced by the ability to prevent thoracic flexion while independently reaching forwards (Figure 7.17). There must be no movement into thoracic flexion. There should be no provocation of any symptoms under flexion load, so long as the thoracic flexion UCM can be controlled. T45.1 Assessment and rating of low threshold recruitment efficiency of the Bilateral Forward Reach Test The thoracic spine and the back of the head are supported upright against a wall. The person should monitor the control of thoracic flexion by palpating the sternum or clavicles with one hand. Any forward of lowering movement of the sternum or clavicles indicates uncontrolled thoracic flexion. The person is instructed to slowly reach forwards with the other arm. Only reach forwards as far as there is no thoracic flexion (monitored by the hand palpating the sternum) (Figure 7.18). Using feedback from palpating the sternum, the person is trained to control and prevent thoracic flexion and perform independent scapular protraction. The person should self-monitor the control of thoracic flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T45.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T45.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining Once control of the thoracic flexion improves, the person should reach forwards with both arms while using the wall for feedback and support of the thoracic spine (Figure 7.19). Eventually, they can move away from the wall and the exercise can be performed with the thoracic spine unsupported (no wall support). The subject stands upright with the spine in its neutral normal curves, the head directly over the shoulders without chin poke and with the arms resting by the side with the shoulders in a neutral position (Figure 7.20). The person is then instructed to slowly lift both arms into flexion. Without letting the thoracic spine extend (sternum does not lift or move backwards) or the head move backwards, the person should be able to actively reach overhead with both hands into end-range shoulder flexion. Ideally, the person should have the ability to dissociate the thoracic spine from overhead shoulder flexion as evidenced by the ability to prevent thoracic extension while independently reaching overhead to at least 160° bilateral shoulder flexion (Figure 7.21). There must be no movement into thoracic extension. There should be no provocation of any symptoms under overhead load, so long as the thoracic extension UCM can be controlled. T46.1 Assessment and rating of low threshold recruitment efficiency of the Bilateral Overhead Reach Test The person is instructed to slowly flex one arm through range to reach overhead. Only reach overhead as far as there is no thoracic extension (Figure 7.22). Using feedback from the back on the wall (or palpating the sternum), the person is trained to control and prevent thoracic extension and perform independent overhead shoulder flexion. The person should self-monitor the control of thoracic extension UCM with a variety of feedback options (T46.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the extension UCM can be controlled. T46.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining

The thoracic spine

Introduction

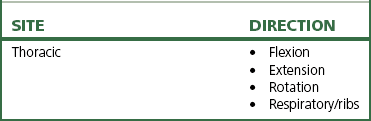

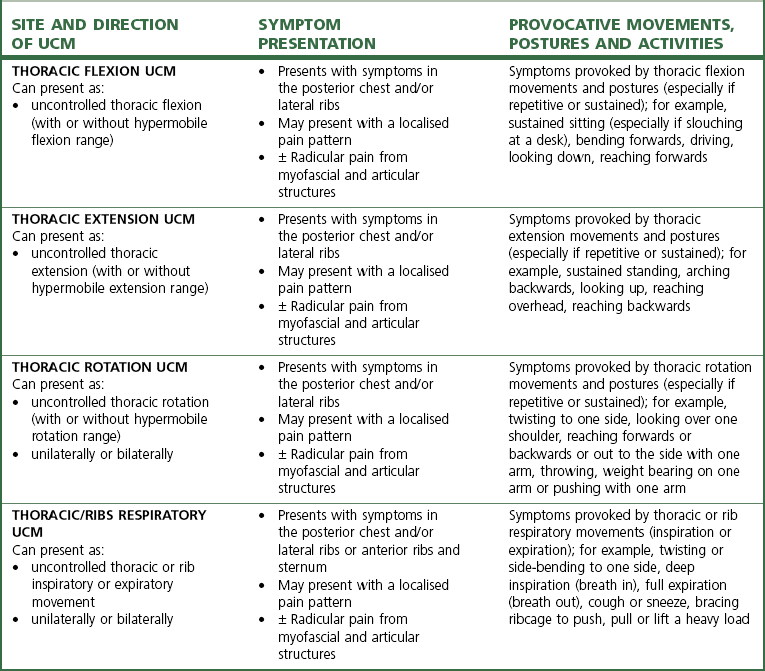

Diagnosis of the site and direction of UCM in the thoracic spine

Linking the site of UCM to symptom presentation

Thoracic flexion control

Thoracic flexion control tests and flexion control rehabilitation

Movement faults associated with thoracic flexion

Relative stiffness (restrictions)

Relative flexibility (potential UCM)

Tests of thoracic flexion control

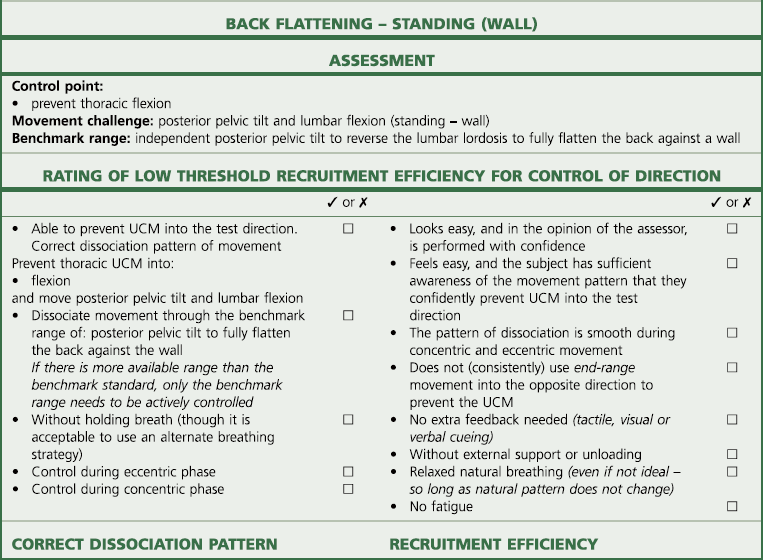

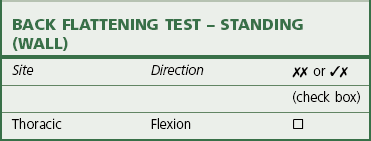

T42 Standing: back flattening test(tests for thoracic flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Rating and diagnosis of thoracic flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

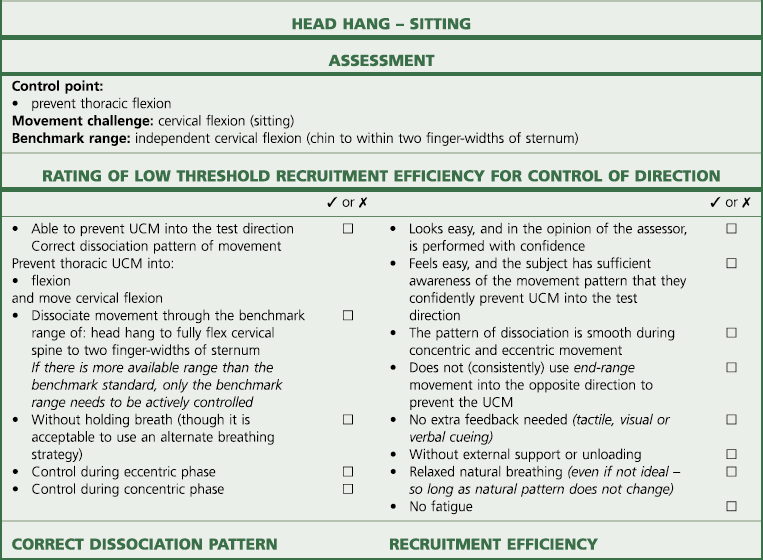

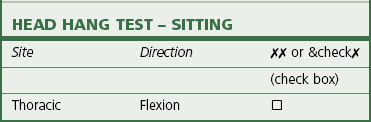

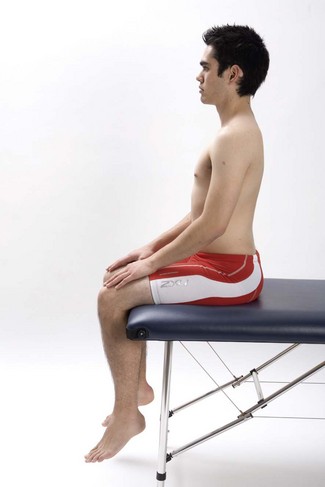

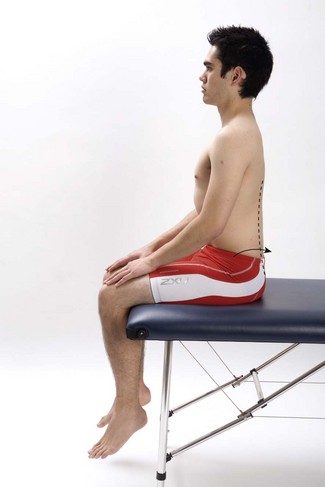

T43 Sitting: head hang test(tests for thoracic flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Rating and diagnosis of thoracic flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

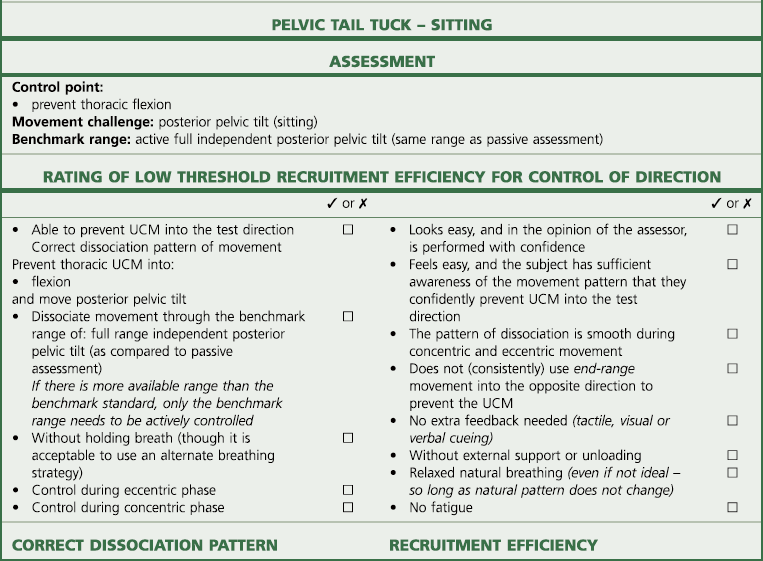

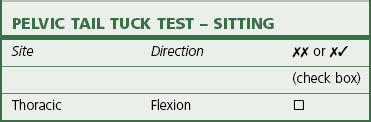

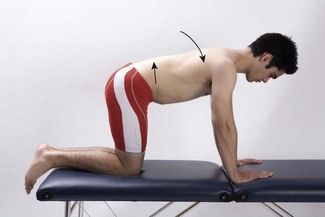

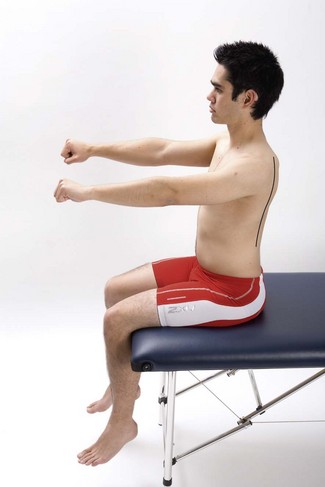

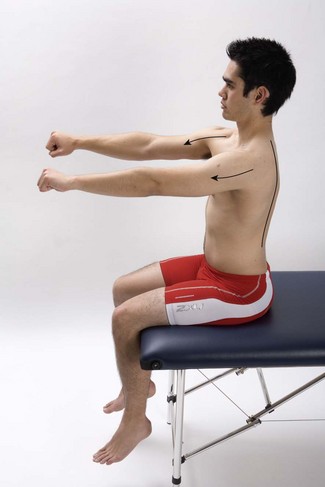

t44 Sitting: pelvic tail tuck test(tests for thoracic flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Rating and diagnosis of thoracic flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

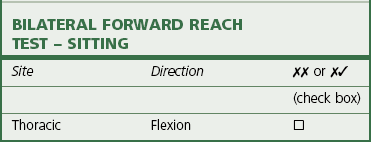

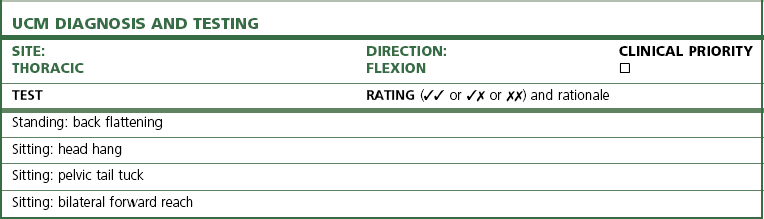

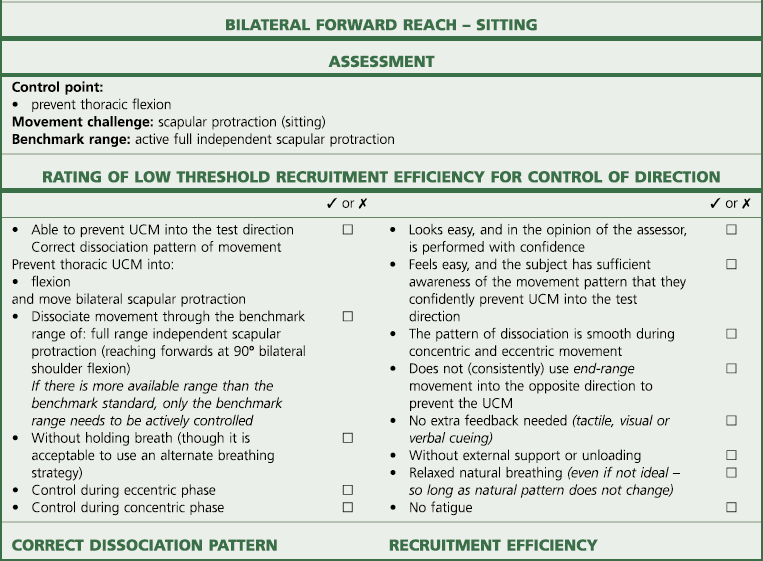

t45 Sitting: bilateral forward reach test(tests for thoracic flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Rating and diagnosis of thoracic flexion uncontrolled movement

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

Thoracic extension control

Extension control tests and extension control rehabilitation

Tests of thoracic extension control

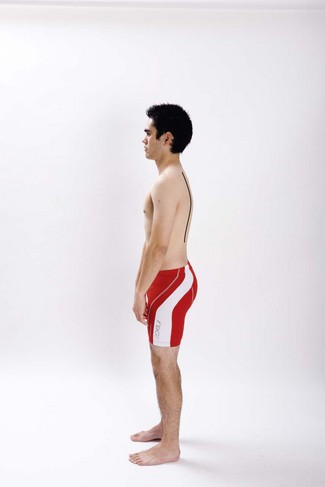

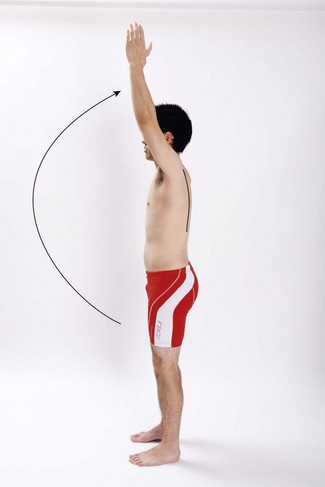

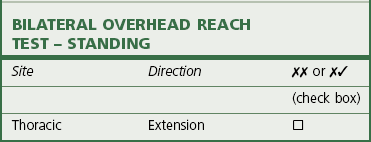

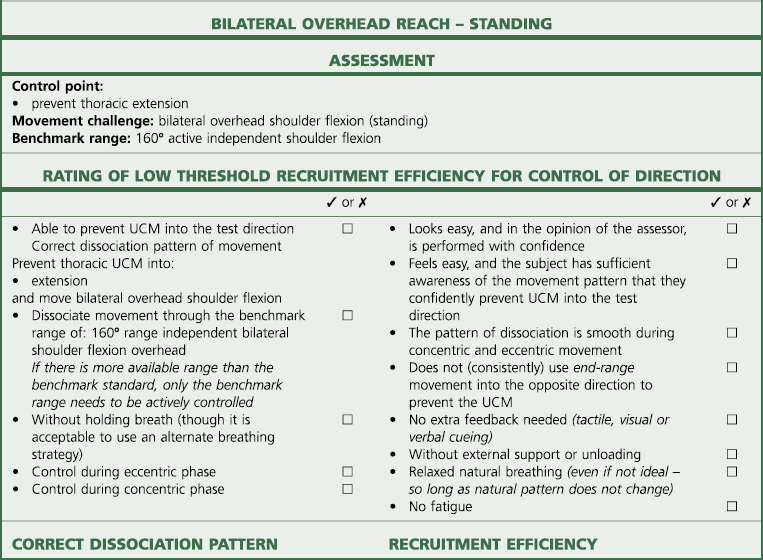

T46 Standing: bilateral overhead reach test(tests for thoracic extension UCM)

Test procedure

Rating and diagnosis of thoracic extension UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The thoracic spine