2 The temporomandibular joint

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is formed by the articulation of the mobile condyle of the mandible with the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone. The mandibular condyle and glenoid fossa are separated by a cartilaginous disc that is aneural and avascular, except at its periphery in the non-load-bearing areas. The disc aids in cushioning and dissipating joint loads, promotes joint stability when chewing, lubricates and nourishes the joint surfaces, and enables joint movements.

The TMJ is a source of head and facial pain; evidence suggests that the majority of patients improve with non-interventional treatment (Toller 1973; Sato 1998, 1999). The term temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is used to describe a variety of medical and dental conditions relating to TMJ dysfunction (TMJD), such as true pathology of the TMJ and involvement of the muscles of mastication.

Four categories of TMD are recognized:

Clinical presentation

Although pain is the commonest symptom of TMJD there are a variety of associated symptoms:

Physical examination

The routine examination of the TMJ includes assessment of general posture, head and neck position, the influences of the thoracic curvature, and scapulae positions. The postural position of the mandible (PPM) is observed. This is the relaxed position of the jaw, and optimal PPM is achieved when the teeth are slightly apart and the lips together; the average space between the upper and lower teeth in the PPM is 3 mm (Beyron 1954). The tip of the tongue should be resting on the roof of the palate, just behind the central incisors, with no pressure of the tongue against the teeth. The lips should be closed and the individual should be able to breathe comfortably through their nose.

Movement abnormalities

The ranges of movement assessed are depression, elevation, protraction, retraction, and left and right lateral movement. If the movement is limited or painful, the mandible can be gently moved passively to assess the true range of movement, and any locking or rigidity felt at the end of range can assist in clinical diagnosis. If extreme muscle spasm is present, there is a rigid end-feel, whereas opening limited by disc displacement without reduction does not have such a firm end-feel (Kraus 1994).

Soft tissue dysfunction

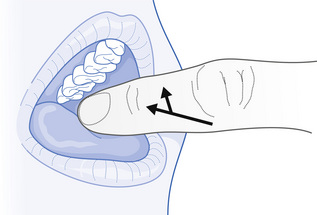

Myofascial pain is a component of most types of TMJD. The major muscles of mastication are the masseter, temporalis, medial, and lateral pterygoid muscles; digastric muscle is an accessory muscle of mastication. The temporalis and masseter muscles can be observed for hypertrophy and atrophy, and should be palpated for muscle texture, tenderness, and myofascial trigger points (MTrPts). The medial and lateral pterygoid muscles are difficult to palpate, and therefore, assessment is carried out using intra-oral palpation (see Fig. 2.1). Tenderness in the facial muscles is a common finding in head and neck musculoskeletal disorders, and it is useful to palpate the muscle of mastication at rest, during muscle contraction, and when on a stretch. It is also important to assess the strength and control of the deep neck flexors and scapula stabilizers. The position of the cervical and thoracic spine affects the PPM, and cervical position has an immediate and lasting influence on mandibular position (Dombrady 1966).

Soft tissue dysfunction is treated with myofascial techniques, manual or acupuncture trigger point deactivation, muscle relaxation, and muscle re-education, where normal movement patterns are taught. Exercises to decrease masticatory muscle activity and, hence, TMJ loading are taught (see below). These exercises also help to counteract habitual jaw bracing.

Open and closing movements

The patient places the tongue in the rest position, and opens and closes the mouth while holding the tongue in a relaxed position. The movement is initially performed slowly and then at speed. It is essential that the patient does not allow the back teeth to clench together during the exercise. It is suggested that this movement has a pumping effect on the joint (McCarthy et al 1992), in which intra-articular pressure is alternately increased and decreased, influencing the movement of fluid and dissolved particles in the interstitial tissues. This exercise also helps to control opening of the mouth and prevents overloading of the TMJ.

Joint dysfunction

When TMJD is unilateral several common joint restrictions can be observed:

Translation

The therapist uses the same hand placement as employed in the previous technique, but the force is applied so that the condyle moves in an anterior direction. This technique can also be performed as a sustained stretch, oscillatory movement and with active movement.

Lateral glide

The therapist stands on the opposite side to the joint involved, and using a gloved hand, places the thumb on the inside of the opposite molars; the other fingers are in a relaxed position over the jaw. The direction of force is lateral, towards the plinth and the patient’s feet. Using a multidirectional force helps to avoid joint discomfort on the contralateral side that may occur if a purely lateral force is used (Kraus 1994).

Mobilizing joint exercises are given to help maintain the increased range of joint motion. The physiological effects of intra-oral techniques are not understood. Nitzan and Dolwick (1991) suggested that an increase in translation occurs as a result of a release of the adherence of the disc to the fossa caused by a reversible effect, such as a vacuum or viscous synovial fluid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree