7 The lumbar spine

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction

The assessment and management of low back pain (LBP) has been shown to be a frustrating and costly challenge for both clinicians and the patients whom they treat (Waddell 1998). Despite the publication of large volumes of research on the subject, evidence regarding the most effective management strategies is limited and often contradictory.

Borkan et al (1998) determined that the greatest difficulties in research into LBP are associated with the individual nature of a patient’s presentation. Upon identifying the importance of this individuality, these authors called for future investigations to focus on the subclassification of patients to facilitate the identification of effective management strategies. Consistent with this is the fact that many randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and the more recent meta-analyses, which do not account for patient-specific presentation, fail to identify effective treatment modalities, since the heterogeneous groupings of patients create a wash out effect in which findings that may have been relevant to a subgroup of patients are not identified.

In the absence of any demonstrable pathology, there has been a growing trend to avoid a specific, patient-centred approach to management and focus instead on a general approach to management, as recommended in the European Guidelines for the management of back pain (Airaksinen et al 2006; Van Tulder et al 2006). The US Joint Clinical Practice Guidelines (Chou et al 2007) identify seven recommendations and categories of LBP that adhere strongly to the European Guidelines.

Recent publications have demonstrated that subclassification leads to both identification of specific dysfunction in certain patient populations (Dankaerts et al 2006) and that treatment based on a classification system improves outcomes (Brennan et al 2006; Cleland et al 2006). Because no one classification system has been shown to encompass all patient presentations, authors have suggested that combinations of systems with weightings on the importance of characteristics between domains for each individual are required (McCarthy et al 2004). This approach reflects the clinical reasoning to assessment and management advocated by many authors (Jones & Rivett 2004), in which consideration is given to determining the presence of any pathoanatomical source of symptoms, the pain mechanisms involved in symptom manifestation, the nature of any movement dysfunction or impairment, and the influence of psychosocial factors. In considering the role of Manual Therapy (MT) in the management of individuals with low back pain, it should be recognized that the manual therapist of today is a different creature to that of 5 to 10 years ago. Manual Therapy now extends beyond the traditional definition, which included manual techniques such as joint mobilization and manipulation to encompass specific exercise therapy, as reflected in the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manual Therapists (IFOMT) definition of Orthopaedic Manual Therapy (www.ifomt.org). Much of this shift in focus occurred following publication of research that identified the role that altered motor control played in the manifestation of many musculoskeletal problems. In a general sense the focus of Manual Therapy is on the treatment of movement dysfunction. In addition to dealing with specific pathoanatomical diagnoses and addressing any relevant psychosocial component to the patient’s presentation, the modern manual therapists needs to direct treatment towards four elements when addressing the movement dysfunction present:

Manual therapy for the relief of pain

Pain is not just a psychological disincentive to move normally. Several recent studies utilizing an experimental pain model have shown changes in motor control and muscle function in both the deep, local system, i.e. the transversus abdominus and multifidus muscles (Hides et al 1994; Hodges & Richardson 1996; Hodges 2001; Hodges et al 2003), and the more superficial trunk muscles, i.e. erector spinae (Gregory et al 2007; Indahl et al 1997), which are usually more associated with phasic activity and movement. It has been proposed that motor control changes result in tissue damage and pain (Sahrmann 1998) through poor movement patterns that place pathological levels of stress on joints and soft tissue. With the recognition that pain can cause subtle but significant alterations in motor function, the potential for a vicious cycle is evident (Moseley & Hodges 2005; Panjabi 1992). Thus, therapists must aim to use all techniques at their disposal to modulate pain mechanisms, including mobilisation, manipulation, massage and acupuncture. The use of traditional Manual Therapy techniques, such as joint mobilization, as methods for relieving pain has long underpinned physiotherapy practice, but it is only in recent years that the neurophysiological effects of Manual Therapy have been investigated. Studies by Sterling et al (2001), Skyba et al (2003), Sluka et al (2006), and Moss et al (2007) have all shown a reduction in hyperalgesia in response to treatment with joint mobilization. Clinically, this rationale is supported by several studies that demonstrate the effect of traditional Manual Therapy as a mechanism of pain relief for patients suffering both acute and chronic LBP (Ferreira et al 2007; Koes et al 2006; van Tulder et al 1997).

Abolishing pain will not necessarily restore correct motor function but it may facilitate rehabilitation aimed at the restoration of normal movement patterns. Hides et al (1996) showed that the resolution of LBP did not correspond with a restoration of normal muscle size in all cases of patients presenting with acute first episode LBP, despite a return to normal function. This alteration in muscle size remained present in some cases at 3-year follow-up, and in many cases it was associated with recurrences of LBP (Hides et al 2001). Likewise, Moseley and Hodges (2000) showed altered motor activity in the presence of experimentally induced LBP that did not resolve spontaneously with the resolution of symptoms in all cases. Other studies showed that subjects who lacked this spontaneous return normal motor control were also more likely to have higher fear/avoidance scores on questionnaires that examined beliefs about pain behaviour. The conclusion of these findings is that long-lasting resolution of pain and restoration of function requires normalization of joint function and muscle behaviour.

Manual therapy to improve joint movement

The role of altered joint mobility in the presence of LBP has long been recognized (Twomey & Taylor 2005). Altered mobility can be characterized as general (i.e. mobility of the trunk as a whole) or segmental (i.e. between two consecutive vertebra). The two most commonly used methods to restore segmental joint mobility to the spinal regions are manipulative thrust and mobilization techniques. Two of the more common mobilization techniques include passive accessory intervertebral movements (PAIVM’s) and passive physiological intervertebral movements (PPIVM’s) as described by Maitland et al (2006).

Studies over several years have questioned the reliability of manual segmental mobilization in both the examination (Seffinger et al 2004) and treatment (Bronfort et al 2004) of patients with spinal pain. In addition, it has been concluded by several authors that manual mobilization is only accurate and reproducible in the presence of pain, and that examination or treatment of altered joint range of motion is flawed (Bogduk 2004).

Recent studies have shown that therapists can reliably detect altered joint stiffness in the absence of pain (Fritz et al 2005; Stochkendahl et al 2006), and that treatment directed at joint restriction/hypomobility can result in improved clinical outcomes (UK BEAM Trial Team 2004). The evidence is strengthened by the use of a subclassification system in which manipulation and mobilization techniques are used only in the management of patients who demonstrate signs and symptoms in their history and physical examination that will respond favourably to this form of treatment, so-called clinical prediction rules (Childs et al 2004; Flynn et al 2002). These criteria included back pain of less than 16 days duration, no symptoms distal to the knee, low fear-avoidance beliefs regarding movement and activity, identification of at least one hypomobile segment of the lumbar spine with posterior–anterior mobilization, and hip internal rotation greater than 35°.

Joint hypomobility is one element of the musculoskeletal system that may be contributing to altered movement within a movement dysfunction paradigm. When managing spinal conditions, it is essential that therapists examine the adjacent joints of the hip, pelvis, and thoracic regions for restrictions of movement. Subgrouping using a movement impairment classification has identified changes in hip function (Van Dillen et al 2007) and pelvic function (Vleeming et al 2008) in certain groups of patients with low back pain. Restoring joint hypomobility in these regions may be important in restoring correct patterns of motion and permitting pain-free function for these individuals.

Manual therapy to normalize muscle activity

In the case of spinal movement dysfunction, evidence of altered motor control abounds in the literature (Hodges & Moseley 2003; Van Dieen et al 2003). Much of the well-publicized literature shows evidence of altered control of the small, deep muscles of the spinal region that have been shown to control shear forces and intra-abdominal pressure during movement (Hides et al 1994; Hodges & Richardson 1996; Pool-Goudzwaard et al 2005; Smith et al 2006). Nevertheless, despite a great deal of research illustrating deficits in this deep, local system in the presence of both actual and experimental pain, there has been no conclusive evidence that treatment regimes aimed at addressing these deficits have a significant effect on LBP or result in improved function.

Critics of spinal stabilizing exercises argue that this lack of evidence suggests that the presence of these motor control deficits are overemphasized in the management of spinal dysfunction and that psychosocial factors are of greater importance. Many of these researchers advocate treatment utilizing pain education and cognitive behavioural therapy in patient management with what has become known as a hands-off approach (Frost et al 2004; Hay et al 2005; Watson 2007). Together, this hands-off approach and the growth of the core stability concept have seen a reduction in the use of traditional Manual Therapy techniques by clinicians. An overemphasis on spinal stability has led to therapists treating all patients suffering from chronic LBP with stabilization exercises and pain education, while failing to recognize the more complex nature of the motor control dysfunctions that exist in patients with LBP (O’Sullivan 2005).

It would seem that motor control training has suffered the same fate as physical interventions in general, in that much of the evidence has failed to account for patient-specific presentations, and instead, investigates the effect of a particular exercise programme on heterogeneous groupings of patients. The use of patient subclassification has begun to highlight altered muscle activity that may previously have been obscured within the data, in which patients who demonstrated a reduction in activity of certain muscles negated the presence of overactivity in other subjects (Dankaerts et al 2006; Hodges et al 2007). Specifically, subgrouping has shown that, in addition to a deficit in the function of the deep, local muscles, subjects with LBP often demonstrate elements of muscular overactivity. The presentation of this muscle overactivity is more variable than the timing delay consistently reported in the transversus abdominis, multifidus, diaphragm, and the pelvic floor muscles. Studies have demonstrated changes in the activity of the erector spinae in specific groups of patients with LBP (Geisser et al 2005; Gregory et al 2007). Similar findings are seen with respect to the flexion relaxation response of the low back muscles, and the hamstrings (Leinonen et al 2000), quadratus lumborum, external oblique, rectus abdominis (Silfies et al 2005), and gluteus medius (Nelson-Wong et al 2008).

A recent study by Hodges et al (2007) highlighted the potential problem of an excessive focus on the timing delay often present in the deep local muscle system. In a group of patients with experimentally induced pain, a net increase in trunk muscle activity was evident, suggesting a need to reduce the activation of some muscles. Together with the work of Reeves et al (2007), the above study suggests that interventions should be aimed at optimizing rather than increasing stability using a combination of both increasing and reducing muscle activation to restore a normal motor control pattern.

The potential for overactivity of these muscles to be a source of pain has been well documented by JG Travell and DG Simons in their work detailing the trigger point (TrPt) referral patterns of various muscles. A myofascial trigger point (MTrPt) is a hyperirritable spot, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle, that is painful on compression and can give rise to characteristic referred pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena (Simons et al 1998). It has been postulated that altered or increased muscle activity may result in pain in the low back and pelvic region because of the development of both active and latent trigger points. Likewise, the presence of definitive lumbopelvic pathology, such as a lumbar disc irritation or hip joint irritation may result in muscular referred pain not specifically related to the initial pathology (Indahl et al 1997).

Support exists for an association between the use of spinal mobilization, manipulation, and improved muscle function (Lehman et al 2001; Sterling et al 2001). Although the exact mechanism is not fully understood, several researchers have demonstrated altered reflex activity following spinal manipulation (Herzog et al 1999; Katavich 1998; Murphy et al 1995). In a review of the neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation, Pickar (2002) concluded that manipulation evokes paraspinal muscle reflexes and alters motorneuron excitability, but that the effects of spinal manipulation on these somato-somatic reflexes may be quite complex, producing excitatory and inhibitory effects. Studies by Lehman et al (2001) and Lehman and McGill (2001) have shown a reduction in exaggerated muscle activity in the trunk muscles of subjects with LBP in response to manipulation. These studies would suggest that traditional Manual Therapy is capable of both reducing the trunk muscle activity seen in patients with LBP and reducing the pain and overactivity seen in the presence of TrPts.

Other non-invasive methods of treating TrPts that have traditionally been utilized by manual therapists include stretching (Huguenin 2004) and active release techniques (Lee 2004). In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the use of dry needling to manage TrPts. This technique involves the insertion of an acupuncture needle into the region of the TrPts aiming to reproduce the patient’s symptoms and stimulate a local muscle twitch response (Shah et al 2006), and it is becoming a common tool in the repertoire of the modern manual therapist. The treatment of TrPts within a movement dysfunction paradigm would suggest that these areas of overactivity are commonly associated with the presence of altered control elsewhere within the system that must be addressed for optimal stability and control.

Exercise therapy and motor retraining

The past 10 years have seen major changes in our understanding of the role that the muscular system plays in the manifestation of back pain. The clinician is no longer focused solely on muscular strength as a management strategy; instead the focus has shifted towards the control of spinal movement. The role of the muscle system in helping the spine function in an optimal fashion is dependant on its ability to match the timing and pattern of muscle recruitment with the constantly changing demands placed upon the system (Hodges 2000). Well-known studies by several authors have shown alterations in the timing and activation of the deep muscle system, including the transversus abdominis (Hodges & Richardson 1996); multifidus (Moseley et al 2004); diaphragm (Hodges et al 2002); and pelvic floor (Smith et al 2007). It is this work that has received overwhelming attention in modern Manual Therapy and has potentially led to an excessive focus in treatment. Studies by Hides et al (1994) and Tsao and Hodges (2007) have shown that addressing these deficits with very specific motor training is capable of normalizing the motor function of these deep muscles; yet clinical trials examining the benefit of stabilization exercises have failed to show any greater benefit than other treatment, including the use of general exercise (Cairns et al 2006; Hayden et al 2005b).

It would seem logical to imagine that improved motor control and function would result from releasing overactive muscle and reducing tone, in addition to normalizing activity of the transversus abdominis and segmental multifidus where functional deficits are commonly seen. To date, much of the research work looking at the use of motor retraining has focused on activation patterns of the transversus abdominis and multifidus muscles, and has not addressed potential overactivity and the presence of TrPts (Ferreira et al 2007; Koumantakis et al 2005; Standaert et al 2008). It may be because of this lack of attention to muscular overactivity that these studies have failed to show a benefit from retraining, despite overwhelming evidence that dysfunction exists in the local muscle system. Likewise, appropriate use of deep muscle retraining exercises in patients who have been subclassified as having a deficit in this element of their motor control pattern results in better outcomes than a general application to any patient experiencing LBP (Hicks et al 2005).

Conclusion

Current evidence would suggest that the manual therapist has a valuable role to play in managing LBP by addressing movement dysfunction. However, because of the variable nature of patients’ presentations, detailed assessment of motor control, muscular overactivity, joint hypomobility, pain response, and psychosocial factors are all essential in order to determine the nature of the underlying condition and establish the most effective treatment approaches.

7.1 Acupuncture in low back pain

Acute back pain

The mechanisms by which acupuncture reduces pain levels have been thoroughly studied (Bowsher 1998; Carlsson 2002; Clement-Jones et al 1980; Ma 2004; Pomeranz 1996); there are thought to be three mechanisms of pain relief that acupuncture seems to trigger (Lundeberg 1998, cited in Bradnam 2007). Primarily, pain relief is initiated at the periphery by axonal reflexes, dichotomizing nerve fibres, local endorphin release, and the release of neuropeptides (i.e. substance P, bradykinin, prostaglandins, histamine) from afferent nerve endings (Carlsson 2002; Kaptchuk 2002). Here, neuropeptides produce local vasodilation and control local immune response, thereby improving tissue healing. Secondarily, according to pain-gate theory (Wall 1978; Wall et al 1984), acupuncture is thought to reduce pain through the spinal mechanisms, by attenuating the nociceptive input in to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Needling also alters the sympathetic outflow (Sato et al 1997, cited in Bradnam 2007) and changes motor output (Yu et al 1995, cited in Bradnam 2007). Spinal effects have the potential to produce strong analgesic effects and may occur immediately (Bradnam 2007; Irnich 2002).

Finally, acupuncture provides pain relief through the activation of pathways from the brain, via diffuse noxious inhibitory controls and descending inhibitory pathways from the hypothalamus to the periaqueductal grey matter (PAG) in the brainstem (Takeshige et al 1992), utilizing neurohormonal responses and central control of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) (Bradnam 2007; Carlsson 2002).

Acupuncture may be used as an anti-inflammatory agent, although the potential anti-inflammatory effects of this treatment remain controversial in clinical trials and the underlying mechanisms are still unclear (Kim et al 2006). Systemic opioids can modulate inflammatory reactions in both the central nervous system (CNS) and at peripheral sites (McDougall et al 2004). McDougall et al (2004) demonstrated that both high-frequency electroacupuncture (HFEA) at 80 to 100 Hz, and low-frequency electroacupuncture (LFEA) at 2 to 4 Hz, applied at acupoint Stomach (ST) 36, significantly reduced peripheral leukocyte migration at the peripheral inflammatory site. Their result is consistent with the theory that specific acupuncture point stimulation as opposed to non-acupuncture stimulation is required to efficiently produce an anti-inflammatory effect (Carneiro et al 2005). Both acupuncture and EA have been shown to enhance opioid release under inflammatory conditions, as compared to the normal state (Ceccherelli et al 1999; Sekido et al 2004), provided de Qi is achieved at the acupoint. Both laboratory and clinical evidence have shown that it is the parasympathetic nervous system that plays the leading role in the down-regulation of cytokine synthesis and the containment of somatic inflammation (Kavoussi & Ross 2007).

The vagal nerve outflow innervates the major organs and has been found to play a systemic immunoregulatory and homeostatic role known as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (Tracey 2002). The parasympathetic origin of the non-specific anti-inflammatory actions of acupuncture stimulates the vagal nerve, and inhibits the inflammatory response and suppresses the development of paw swelling and inflammation in mice (de Jong et al 2005).

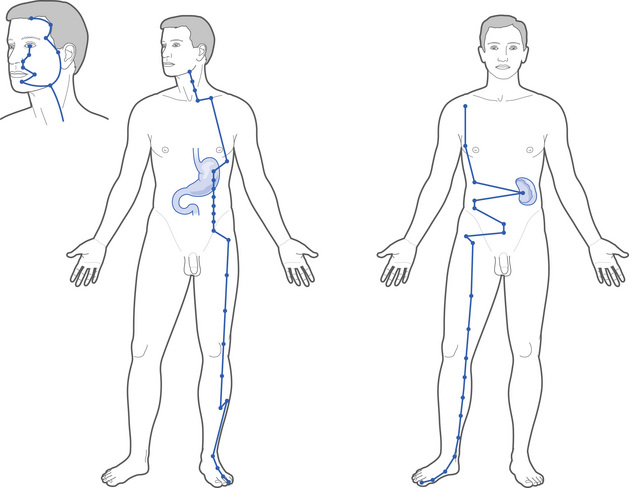

The cholinergic pathway proposed by Tracey (2002) could offer a plausible mechanism for the anti-inflammatory effects of acupuncture (Andersson 2005), supporting the use of auricular acupuncture where the vagal nerve is easily stimulated and may produce a systemic anti-inflammatory effect (Ulett & Han 2002). Sections of the Stomach and Spleen meridians (Fig. 7.1) known to generate parasympathetic stimuli correspond closely to the path of the vagal nerve and may contribute to the acupuncture action of homeostasis by regulating interactions between the ANS and the CNS, the Yin and Yang of the regulatory action of homeostasis.

Chronic low back pain

Chronic LBP is a common complaint, with up to 80% of the UK population reporting an episode during their lifetime (Dillingham 1995). Despite the prevalence and the increasing cost of LBP there is much debate and conflicting evidence regarding the most effective management for this condition. Recent Cochrane reviews (Assendelft et al 2004; Furlan et al 2005; Hayden et al 2005a) investigating various forms of management for chronic LBP do not appear to recommend one specific treatment approach. As a consequence more people are turning to complementary therapies, including acupuncture, to help manage their symptoms. There have been many recent RCTs investigating the efficacy of acupuncture for chronic LBP; however, it is difficult to draw conclusions from many of these studies due to methodological flaws. A Cochrane systematic review (Furlan et al 2005

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree