The Stiff Knee: Ankylosis and Flexion

Chitranjan S. Ranawat

William F. Flynn Jr.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Knees with less than a 50° arc of motion are considered “stiff,” but there is a wide variation in presentation. One may be faced with a knee ankylosed in extension or one with flexion of 0° to 50°. The surgeon who is to successfully correct such problems with an arthroplasty must have a clear plan in mind.

The approach to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the patient with a stiff knee is similar to planning the revision of a TKA. One must first identify the reason for the lack of motion. Some of the most common causes are previous surgery on the knee; previous injury to the knee; ankylosis, particularly in rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis; reflex sympathetic dystrophy; severe pain; neuromuscular disorder; and previous infection.

The underlying cause of stiffness of the knee can have a profound effect on the success of the proposed surgery. Mechanical problems (bony deformity and ligamentous and capsular contracture) can usually be addressed successfully. Severe pain may limit motion with an alert patient; the same patient anesthetized may have a much better range of motion (ROM). Patients with severe reflex sympathetic dystrophy may have very limited motion, and surgery in these patients should be approached very cautiously because it can exacerbate this disorder. Patients with neuromuscular disorders, including those who have had a stroke, should also be approached with caution, because one cannot correct their underlying disorder. Patients with a history of knee sepsis may also have a stiff knee. Before considering arthroplasty, one must absolutely rule out low-grade sepsis.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The pathologic anatomic conditions encountered in cases of stiffness of the knee may include shortening and tightness of the ligaments and muscles, fibrosis of the quadriceps muscle, intraarticular or extraarticular fibrosis, and intraarticular or extraarticular bony blocks from malalignment or new bone formation. The surgeon must be able to address any or all of these conditions.

Preoperative planning for arthroplasty of the stiff knee must include a thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation of the knee. The preoperative ROM of the knee must be documented, along with any contractures, scars, or angular deformity. The circulation and sensation in the limb, and its motor function, particularly with regard to the quadriceps muscle, must be assessed. In addition, as in the case of any surgery, the patient’s overall condition must be evaluated preoperatively, including the patient’s desire and ability to comply with postoperative therapy.

Radiographic evaluation must include anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and patellar views, with additional studies such as computed tomography (CT), bone scans, or scanogram added as needed. As in a revision situation, alignment, bone loss, and bone quality must also be assessed. Additionally,

any hardware present around the knee and that which will have to be removed must be identified so appropriate instrumentation for accomplishing this will be available at the time of surgery.

any hardware present around the knee and that which will have to be removed must be identified so appropriate instrumentation for accomplishing this will be available at the time of surgery.

Finally, the surgeon must decide which prosthesis to use. A wide variety of modular systems are available and can accommodate almost any situation, but occasionally a custom prosthesis must be fabricated for a very small or large knee or a knee with severe bone loss or malalignment. Careful consideration must be given to expected soft-tissue deficiencies. With severe deformity, the posterior cruciate ligament is usually abnormal and the prosthesis must substitute for it. Additionally, the collateral ligaments may be deficient or may become functionally deficient if extensive soft-tissue releases are required, and a constrained option must be available.

SURGERY

Once preoperative planning is complete and an appropriate prosthesis has been selected, the surgeon can proceed. In a laminar flow operating room, the patient is put in the supine position with a tourniquet on the thigh of the leg that will undergo surgery. The leg is draped free, and a Vi drape is used to isolate the operative field. We use epidural anesthesia in all knee replacements. This technique is very safe and effective, and it provides the additional benefit of permitting the patient to be maintained postoperatively on continuous infusion. This dramatically decreases the patient’s postoperative pain and narcotic usage.

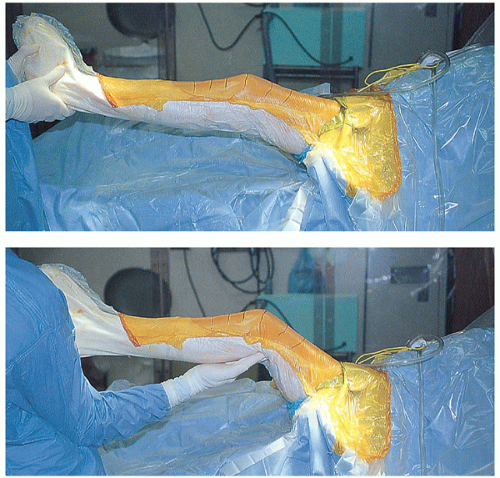

The patient’s ROM and ligamentous stability should be assessed under anesthesia prior to incision (Figs. 12-1 and 12-2). If there is no previous incision, a straight midline or slightly paramedian incision should be used. Old incisions should be incorporated as much as possible into new ones, making sure to leave no avascular islands or narrow strips of skin.

A medial parapatellar arthrotomy is then performed along the junction of the quadriceps tendon and vastus medialis muscle (Fig. 12-3). If the patella is ankylosed, it may be osteotomized at this time. Any adhesions between the quadriceps and femur on either side of the patella and gutter are released, and the quadriceps is mobilized from the femur (Figs. 12-4, 12-5, 12-6, 12-7, 12-8 and 12-9). Flexion of the knee is now assessed. If the knee cannot be flexed more than 30 degrees to 40 degrees, we perform a quadriceps release rather than a V-Y turndown or tibial tubercle osteotomy. A V-Y turndown devascularizes the extensor mechanism, and adjusting the final length of the quadriceps mechanism is difficult. Small tubercle osteotomies may create problems with nonunion or loss of fixation, and large osteotomies require substantial fixation. In addition, any tubercle osteotomy can change the position of the patella, and the final adjustment of quadriceps tension is again somewhat problematic.

Quadriceps Release

With the knee in extension, the patella is everted and the patellofemoral ligaments are released with electrocautery. Next, we routinely perform a lateral retinacular release from the inside out (Fig. 12-10). If preservation of the superior genicular artery prevents an adequate release, we sacrifice the artery.

After this, a careful dissection is done, releasing the vastus medialis, medial capsule, and superficial medial collateral ligament (MCL) from the medial and anterior femur, as well as leaving the superior attachment of the deep MCL, thus forming a long sleeve subperiosteally (Fig. 12-11). The dissection of the MCL is done subperiosteally to about the midplane of the tibia. If the tibia and femur are ankylosed, an osteotomy is performed at the joint line; in other cases, scar tissue in the joint is excised with a scalpel and the cruciate ligaments and menisci are released (Fig. 12-12). If the knee cannot be flexed at least 30 degrees to 40 degrees because of a tight quadriceps mechanism, a controlled Z-lengthening is done of the rectus femoris and vastus intermedius muscles, using six to eight small incisions made with a no. 11 blade. The rectus is first separated from the vastus, and the knee is then flexed to keep tension on the tendon. With each Z, the flexion of the knee increases in a controlled fashion, until 70 degrees to 80 degrees of flexion is reached (Figs. 12-13, 12-14 and 12-15).

Once this is accomplished, the knee is flexed with the patella everted, occasionally without dislocation, and the tibia is externally rotated to avoid avulsing the tendon from the tubercle (Fig. 12-16). The subperiosteal medial release is then continued as the knee is further flexed and the tibia externally rotated. The release is carried around medially and posteriorly to at least the midplane of the tibia (Figs. 12-17, 12-18 and 12-19). The attachment of the MCL to the femur is not detached subperiosteally unless it interferes with the balance of the soft-tissue sleeve once the trial implant is in place. Any remnant of the medial meniscus is carefully released.

FIGURES 12-1 AND 12-2 Preoperative extension (−20 degrees) and flexion (50 degrees). Note that the leg is draped free. |

Dissection is now done laterally with the knee flexed. The remaining patellofemoral ligaments are released (Figs. 12-20 and 12-21). The insertion of the iliotibial band is identified and preserved. The lateral capsular structures, including the popliteus and lateral collateral ligament, are released from the femur subperiosteally, using either a knife or an osteotome (Figs. 12-22, 12-23 and 12-24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree