14 The shoulder region

The mechanics of the shoulder are rather complex. The shoulder ‘joint’ in fact comprises three components – the gleno-humeral joint or shoulder joint proper, the acromio-clavicular joint, and the sterno-clavicular joint. The gleno-humeral joint allows a free range of abduction, flexion, and rotation, under the control of the scapulo-humeral and pectoral muscles. The other two joints together allow 90 ° of rotation of the scapula upon the thorax and a moderate range of antero-posterior gliding of the scapula, under the control of the cervico-scapular and thoraco-scapular muscles.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF SHOULDER SYMPTOMS

Exposure

The patient must be stripped to the waist. The examination is conducted most easily with the patient standing; alternatively he may sit upon a high stool. For the greater part of the examination the surgeon stands behind the patient, so that he may observe more easily the position of the scapula.

Steps in routine examination

A suggested plan for the routine examination of the shoulder is summarised in Table 14.1.

Table 14.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the shoulder

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE SHOULDER REGION | |

| Inspection | Power |

| Bone contours alignment | Cervico-scapular and thoraco-scapular muscles (controlling scapular movement)—Test elevation of scapula, retraction of scapula, abduction-rotation of scapula |

| Soft-tissue contours | |

| Colour and texture of skin | |

| Scars or sinuses | |

| Palpation | |

| Skin temperature | Scapulo-humeral muscles (controlling movement at gleno-humeral joint)—Abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, lateral rotation, medial rotation |

| Bone contours | |

| Soft-tissue contours | |

| Local tenderness | |

| Movements | Acromio-clavicular joint |

| Distinguish between true gleno-humeral movement and scapular movement during abduction, flexion, extension, lateral rotation, and medial rotation | Examine for swelling, increased warmth, tenderness, pain on movement, and stability |

| ?Pain on movement | |

| ?Muscle spasm | |

| ?Crepitation on movement | |

| Sterno-clavicular joint | |

| Examine for swelling, increased warmth, tenderness, pain on movement, and stability | |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF SHOULDER SYMPTOMS | |

| 3. GENERAL EXAMINATION | |

| General survey of other parts of the body | |

Movements at the shoulder

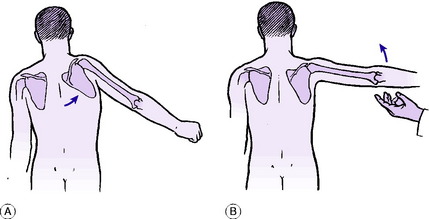

In examining shoulder movements it is important to determine how much of the movement occurs at the gleno-humeral joint and how much is contributed by rotation of the scapula. An accurate distinction between the two types of movement can be made only by grasping the lower half of the scapula so that its movements can be detected (Fig. 14.1). In the normal shoulder about half the range of abduction occurs at the gleno-humeral joint and half by scapular rotation. Disorders of the shoulder generally cause restriction of gleno-humeral movement rather than of scapular movement. If the shoulder joint proper (the gleno-humeral joint) is fused, either naturally or by operation, a range of abduction of up to 60 or 80 ° is possible by scapular movement alone.

Stand behind the patient. Abduction: Instruct the patient to try to raise both arms sideways from the body so that the palms of the hands meet above the head. Measure the range, and observe what proportion of the movement takes place at the gleno-humeral joint and how much is contributed by rotation of the scapula upon the thorax. Flexion: Instruct the patient to raise the arms forwards towards the vertical. Again observe (by means of the hand upon the scapula) what proportion of the movement occurs at the gleno-humeral joint and how much is contributed by rotation of the scapula on the chest wall. Extension: Ask the patient to raise the elbows backwards. Lateral (external) rotation: The elbows are held in to the sides and are flexed 90 ° (Fig. 14.2): the forearms then serve as convenient pointers to indicate the angle of rotation (normal range = 80 °). Medial (internal) rotation: Instruct the patient to place the back of his hand in contact with his lumbar region and to carry the elbow forwards, bringing the finger tips up as high as possible between the shoulder blades (normal range = 110 °).

Estimation of muscle power

In estimating the power of the shoulder muscles two groups must be distinguished:

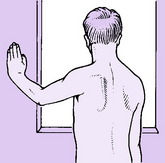

The cervico-scapular and thoraco-scapular muscles. These control movements of the scapula. Estimate the power of each group in turn and compare on the two sides. Elevators of the scapula (levator scapulae, upper fibres of trapezius): Instruct the patient to shrug the shoulders against the resistance of the examiner’s hands. Retractors of the scapula (rhomboids and middle fibres of trapezius): Instruct the patient to brace the shoulders back. Abductor-rotators of the scapula (serratus anterior, with middle and lower fibres of trapezius): Instruct the patient to push horizontally forwards with the hand against a wall (Fig. 14.3) or simply to raise the arm from the side. If the serratus anterior is weak, winging of the scapula (backward projection of its vertebral border) will be observed (Fig. 14.3).

The scapulo-humeral muscles. These control movements of the gleno-humeral joint. Estimate the power of each muscle group, testing in turn the abductors, adductors, flexors, extensors, lateral rotators, and medial rotators. If the patient has lost the power to initiate active gleno-humeral movement from the dependent position, determine whether he can maintain abduction when the limb has been raised with assistance to 90 °. Ability to sustain abduction but not to initiate it is characteristic of isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon (see Fig. 14.12, p. 267).

The acromio-clavicular and sterno-clavicular joints

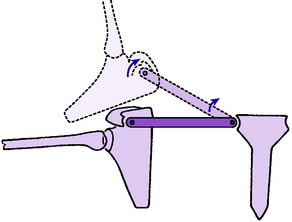

The clavicle may be regarded as a link, jointed at each end, connecting the scapula to the sternum (Fig. 14.4). Movement of the scapula must occur about a fulcrum at one or both ends of this link. In the normal shoulder movement of the scapula, with consequent movement at the acromio-clavicular and sterno-clavicular joints, occurs mainly:

Radiographic examination

Gleno-humeral joint. The routine shoulder film is a plain antero-posterior projection with the limb in the anatomical position. When additional information is required a special axillary projection with the arm abducted 90 ° (giving a lateral view of the humerus) should be obtained. Further films showing the upper end of the humerus in varying degrees of rotation are sometimes informative. Arthrography, after injection of radio-opaque fluid into the joint, will show whether or not the capsule is intact.

Other imaging techniques

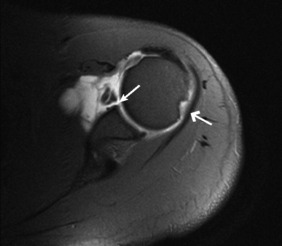

Radioisotope scanning, computerised tomography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging must each be considered in appropriate circumstances. Double contrast arthrography combined with computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be particularly valuable in demonstrating the extent of soft tissue damage in recurrent dislocation of the shoulder (see Fig. 14.10).

Extrinsic sources of shoulder and arm pain

In many cases in which the main complaint is of pain in the shoulder or arm there is no local abnormality, the symptoms being referred from a lesion elsewhere. Thus pain over the shoulder is a common symptom in affections of the neck, especially when the brachial plexus or its roots are involved. Shoulder pain is also a feature of irritative lesions in contact with the diaphragm, either in the thorax or in the abdomen. The possibility of such extrinsic lesions must always be considered in the investigation of shoulder pain.

DISORDERS OF THE SHOULDER (GLENO-HUMERAL) JOINT

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of arthritis, p. 96)

Pyogenic arthritis of the shoulder is uncommon. It may complicate a penetrating wound, or it may be a haematogenous (blood borne) infection. In children infection may spread to the shoulder from a focus of osteomyelitis in the upper metaphysis of the humerus (p. 279).

The clinical features resemble those of pyogenic arthritis of other joints. The onset is rapid and is accompanied by pyrexia. The shoulder is swollen and abnormally warm, and all movements are greatly restricted. Treatment follows the lines suggested on page 98.

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of tuberculous arthritis, p. 98)

The pathological and clinical features correspond to those of tuberculous arthritis in any major joint. Treatment with antituberculous drugs follows the general principles outlined on page 102. In early cases good recovery of function may occur, but in more advanced cases of bone and joint destruction surgical intervention with arthrodesis of the joint may be required.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

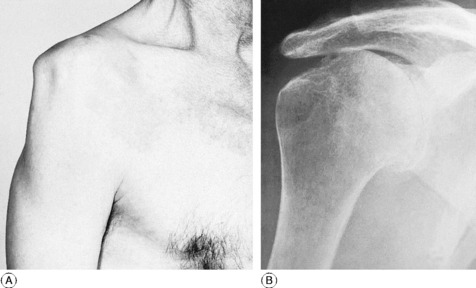

As in other superficial joints, the main clinical features are local pain and stiffness, increased warmth, swelling from synovial thickening, and marked restriction of movement. There is wasting of the deltoid muscle, with consequent flattening of the shoulder contour (Fig. 14.5A). Radiographs show rare-faction of bone, narrowing of the cartilage space, and eventually erosion of bone at the joint margins (Fig. 14.5B).