Fig. 10.1

This figure depicts the repair. Please note the direction of suture placement in the muscle and in the pubic tubercle as depicted by the dashed line. The goal is to broaden the rectus insertion by suturing it medially to the pubic tubercle and then extending this repair a short distance attaching the rectus to the shelving portion of the inguinal ligament to reinforce any defect or bulge in the posterior wall

Although a number of operative approaches have been described for athletic pubalgia (sports hernia), we have adopted an open surgical approach that broadens the rectus insertion and reinforces the posterior wall of the inguinal canal with sutures. Although a number of open, sutured repairs have been utilized for athletic pubalgia [3, 8, 17, 36–39], they are all variations of well-established techniques in conventional groin hernia surgery. In addition, open onlay mesh repairs [40–43] and laparoscopic TEP [15, 26, 44–47] or TAPP mesh repairs [48–50] have also been described. Any of the described repairs may or may not include division of some of the nerves in the groin, such as the genital branch of the genito-femoral nerve, the ilio-inguinal nerve, or the iliohypogastric nerve [17, 42].

Our approach to repair in high-performance athletes with athletic pubalgia is to perform an open sutured repair, with the expectation that they will be able to return to full activity at a high level of performance in the vast majority of cases. Occasionally, a patient presenting with athletic pubalgia will have a definite conventional groin hernia (direct or indirect), with a clinically detectable bulge in the groin. In these circumstances, we tend to favor a laparoscopic approach to hernia repair with pre-peritoneal mesh placement (the TAPP procedure). Patients suspected of athletic pubalgia are referred to the University of Massachusetts Sports Medicine clinic for outpatient evaluation. During this visit, the patient is assessed by two surgeons: an orthopedic surgeon subspecializing in sports medicine, and a general surgeon with a special interest in groin hernia surgery. Patients are carefully evaluated for other abdominal conditions, the presence of conventional groin hernias, as well as for the signs and symptoms seen in athletic pubalgia. A complete evaluation of the hip and thigh muscles is undertaken. Further investigations, such as imaging, are carried out if necessary. Thereafter, a decision for surgery will be made.

Approach to Physical Exam

When patients present to our clinic with symptoms and history consistent with athletic pubalgia, our approach is as follows. We first seek to determine where the pain is located, what makes it better or worse, if there is any pain at rest, and if there are any associated bowel or bladder symptoms or testicular pain. In our experience, the typical patient presenting with this condition will have either pinpoint or more generalized pain in the region of the distal rectus abdominis at its insertion on the pubis. This pain may radiate into the adductor region, perineum, rectus muscles, inguinal ligament, or testicular area. The most consistent and the most diagnostic physical exam finding is insertional rectus pain at the pubis, with accentuation of this pain by having the patient performing a sit-up while the examiner applies pressure to the distal rectus abdominis insertion (Fig. 10.2). This provocative maneuver most often reproduces the patient’s pain over the pubic insertion site of the rectus abdominis (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.2

Sit-up accentuates pain at rectus

Fig. 10.3

Provocative maneuver to test for athletic pubalgia

In addition to this examination, a thorough bilateral hip examination is preformed, focusing on passive range of motion, particularly symmetry and any pain production with hip motion. When the patient’s history and examination seems to suggest a component of FAI, hip radiographs are obtained. We typically obtain an AP pelvis, AP and lateral hip, and 45° Dunn view, which has been shown to accurately diagnose cam FAI [28].

The Dunn view had been particularly useful in detecting femoral head asphericity consistent with the cam-type FAI. Once the patient has been evaluated by an orthopedic sports medicine surgeon with extensive experience in treating athletic pubalgia, the patient is next evaluated by a general surgeon who also possesses extensive experience in diagnosing and treating this condition. We believe that this multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and treatment of athletic pubalgia has led to the high rate of successful outcomes and low re-operation rates that we have experienced at our institution.

Approach to Surgery

Our approach is to perform this operation under general anesthesia. General anesthesia with an endotracheal airway is carried out. We perform preemptive analgesia with 0.25 % Marcaine at the proposed site of the skin incision, and an ilio-inguinal nerve block is carried out on the same side. A skin crease incision is made in the groin that is 3–4 cm in length (Fig. 10.4). The incision is carried down through the skin and subcutaneous tissues to the level of the external oblique aponeurosis. The surface of the external oblique aponeurosis is exposed down to the external inguinal ring, and the external oblique aponeurosis is opened in the direction of its fibers into the mid-portion of the external inguinal ring. The external oblique is then separated from the spermatic cord and the underlying internal oblique and rectus abdominis. The spermatic cord is bluntly separated from its loose attachments to its surrounding structures and it is encircled with a Penrose drain in order to expose the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. The spermatic cord is freed from its attachments from the pubic tubercle to the internal inguinal ring. Care is taken to preserve all cord structures, and excessive traction on the cord must be avoided. It is critical to dissect the cord free from the pubic tubercle and to uncover the reflected portion of the ilio-inguinal ligament. This entire dissection is identical to standard open hernia repair for a conventional groin hernia.

Fig. 10.4

A 3–4 cm skin crease incision is made in the groin and carried through the external aponeurosis exposed in the direction of its fibers to the external ring. The spermatic cord is encircled and retracted. These steps are well known to the general surgeon

Once the cord is completely mobilized, the posterior wall of the inguinal canal is inspected and any attenuation or bulging is noted. At this point, any injury to the rectus abdominis or conjoined tendon should now be observed and documented. Findings at this point often include: attenuation of the insertion of the rectus, a clear-cut defect in the tendinous portion of the rectus (often with retraction of the muscle), attenuation or separation of the conjoined tendon, and/or attenuation and bulging of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. It must also be noted that there may be no obvious abnormality on inspection.

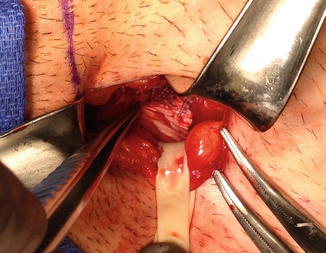

Once exposure is complete, repair is undertaken. First, attention is directed to the pubic tubercle. We utilize electrocautery to roughen the surface of the periosteum of the pubic tubercle. This may allow for better attachment of the tendinous portion of the rectus muscle that will be sutured down to the tubercle. We use #2 ORTHOCORD™ (DePuy Companies, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ), nonabsorbable suture for this repair, as it is less likely to pull through the tissues, and this suture tends to retain its tensile strength over time. The first two stitches are crucial. A good bite along the rectus edge with broad capture of the periosteum is critical to secure the lateral tendinous edge of the rectus to the tubercle. Ideally, this will bring that edge of rectus down to the roughened portion of pubic tubercle. Only the most medial aspect of the floor is opened to expose Cooper’s ligament. The goal of the second stitch is to sequentially grab the rectus edge slightly higher up (i.e., at the lateral tendinous surface) and pull that down to the tubercle and the upper part of Cooper’s ligament (Fig. 10.1). The third stitch will capture Cooper’s ligament, the most lateral edge of the pubic tubercle, and the reflected portion of the ilio-inguinal ligament (Fig. 10.5). Additional sutures are placed to bring the conjoined tendon—rectus interface and the conjoined tendon down to the reflected portion of the ilio-inguinal ligament (Fig. 10.6). This is similar to a Bassini repair. Our repair represents a McVay/Bassini variation.

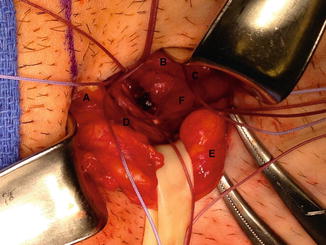

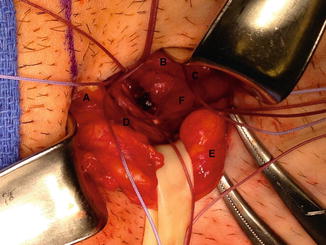

Fig. 10.5

This figure shows the edge of the rectus abdominis with bridging sutures between the lateral edge of rectus (B), the pubic tubercle (A), and the reflected portion of the ilio-inguinal ligament (D). Also note the bulge in the posterior wall (F), the retracted spermatic cord (E), and conjoined tendon (C)

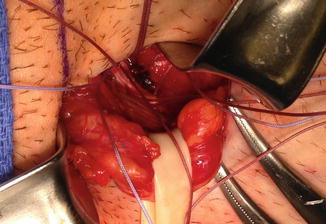

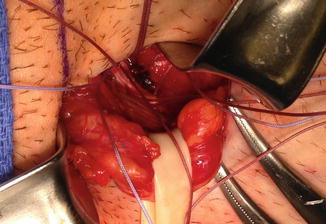

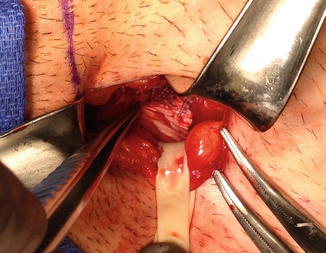

Fig. 10.6

This picture captures the reflected portion of the ilio-inguinal ligament and the bulge in the posterior wall

Since this is not a repair of a conventional hernia per se, the posterior wall reinforcement does not need to extend all the way to the internal ring, which is more likely to cause undue cord compression that is more likely to cause testicular symptomatology. All identified nerves in the groin are preserved. We do not divide the nerves in the groin because we do not believe that the pain syndrome associated with athletic pubalgia is in any way related to neuralgia or nerve entrapment. As stated earlier, nerve-related groin pain is a well-documented sequela of conventional groin hernia surgery, and the type of pain that these patients suffer from does not resemble the pain syndrome associated with athletic pubalgia.

Once the repair is completed (Fig. 10.7), the cord is allowed to fall back into position. The completed repair most often consists of only five sutures. The external oblique aponeurosis is closed with a running 2–0 absorbable suture. Scarpa’s fascia is reapproximated with absorbable sutures and the skin is closed with a running subcuticular absorbable stitch. This sutured approach is preferred for high-performance athletes with typical athletic pubalgia or sports hernia. However, athletes with a clear-cut discernible bulge in the groin and a conventional groin hernia on physical examination will have a laparoscopic TAPP procedure since we believe the recurrence rate of conventional hernias is much lower after laparoscopic repair. These patients should have a mesh repair, which can be carried out either openly or laparoscopically. These repairs will also likely provide enough support to the posterior wall and the rectus abdominis to solve the sports hernia pain syndrome as well.

Fig. 10.7

The completed repair

If the patient presents with adductor longus pain and tenderness to palpation, at the time of athletic pubalgia repair, we consider giving a local injection (consisting of cortisone and 0.25 % Marcaine), to the region of the tendon origin at the inferior aspect of the pubis. Although performed infrequently, in recalcitrant cases we have also performed partial adductor longus tenotomy, tendon recession, or complete tenotomy. The approach to this intervention is through a small skin incision in the groin crease just over the prominence of the adductor longus tendon at its insertion onto the pubis. The incision is carried down to the underlying tendon, and a scalpel is used to perform a partial (or in the case of more severe adductor pain—complete) tenotomy of the adductor longus at its origin. The tissues are closed with an absorbable suture in buried, interrupted fashion, followed by re-approximation of the skin with a running subcuticular monofilament. At our institution, we have achieved better results with the use of tendon injections over tenotomy, and prefer injections whenever it has been determined that the adductor longus tendon should be addressed in addition to the athletic pubalgia repair.

Surgical Outcomes

We recently studied the efficacy of the open, all-suture repair technique for athletic pubalgia in our institution. One hundred and fifty-three patients underwent open athletic pubalgia repair performed by the same two surgeons over a 6-year period from January 2007 through January 2013. Preoperative SF-12 (Short-Form Health Survey) and Tegner activity levels were recorded for 136 patients, whereas iHOT-33 (International Hip Outcome Tool) questionnaires were later added to pre-op surveys in July 2012 (20 pts.). We discovered that four patients required operations on the contralateral side (2.6 %), and no revisions were necessary on the ipsilateral side when the open suture repair technique was used as the index procedure. Four patients would go on to require subsequent hip arthroscopy (2.6 %), but only two were needed on the ipsilateral side (1.3 %). The low rate of ipsilateral revision surgery and/or hip arthroscopy lends support to our approach in the diagnosis of and surgical treatment for athletic pubalgia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree