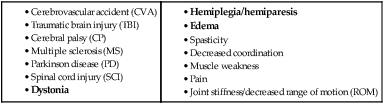

The neurological hand can be complex. Motor and sensory impairments, spasticity/hypertonicity, learned disuse/nonuse, and perceptual issues make rehabilitation of this hand a challenge. And since not every neurological injury or impairment has the same symptoms among clients,1 predicting outcomes in a neurological patient’s hand progress can be difficult. However, when a neurological client makes progress in hand skills or experiences an increase in functional use of his hand, the reward is significant. This chapter is designed to assist clinicians in the assessment and treatment of the neurological hand and to offer suggestions for orthotic options to promote optimal positioning at rest and in function. Brain injury can lead to a broad spectrum of symptoms and disabilities. Persons with an acquired brain injury from CVA and TBI can exhibit motor disorders in which the UEs often show common clinical symptoms, such as spasticity, decreased muscle strength, incoordination, impaired sensation, and inability to bear weight symmetrically.2 It has been estimated that 3 months after a stroke, only 20% of clients attain full recovery of UE function, and 30% to 66% of these individuals are unable to use their affected UE in meaningful activities.3 Intervention to increase hand skills is very individualized, and the level of practical return varies between individuals. Therefore, as therapists, it is important to assess not only functional status but also the priorities of the individual’s hand use. Using neuroimaging techniques to diagnose acute capsular stroke, Wenzelburger and colleagues4 found that lesions in the posterior regions of the internal capsule were associated with chronic dexterity deficits in the affected UE. At baseline assessment, muscle strength was the only predictor significantly associated with dextrous hand function at 6 months post-stroke. Duncan and colleagues5 reported motor and sensory scores on the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA) at day 5 after stroke accounted for 74% of the variance in the composite scores at 6 months post stroke. However, it is not possible to delineate the contribution of UE sensation to the recovery of discrete dextrous hand function from such composite scoring of the sensorimotor functions in the UEs.5 MS is the most common autoimmune, inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). MS is characterized by a combination of damage to both gray matter and white matter with an ensuing loss of tissue leading to cortical atrophy. The neurological symptoms with relation to the hand include sensory disturbances, motor impairment, intention tremor, ataxia, and impaired motor coordination.6 The clinical symptoms of MS are highly variable depending on the site and extent of CNS involvement. However, difficulty with object manipulation caused by deterioration of hand dexterity is a common and important clinical feature with mildly involved MS clients.7 Additionally, UE function seems to be related to a decrease or loss of light touch-pressure and two-point discrimination sensations of the hand, as well as a decrease in elbow flexion strength. UE strengthening and sensorial training of the hand may contribute to increased UE function in clients with MS. Therefore, testing of both static and dynamic manipulation tasks may be needed for a more complete assessment of hand function in various populations. However, an explicit overview of arm-hand training programs is lacking with the MS population. Cervical spinal cord injury (cSCI) can lead to devastating impairments, and yet to date, there is no reliable clinical treatment. In humans, cSCI, including complete and incomplete tetraplegia, represents about 62% of all spinal cord injuries.8 This type of injury can cause severe impairments affecting the use of the UEs. Regaining partial or full function of the arm and hand could make significant improvements in client quality of life, and it is considered to be a priority for clients with cSCI.9 Recently, there has been increasing interest in developing cSCI models in rodents; hence, having sensitive and reliable methods to evaluate forelimb motor functions is of potential importance. Donnelly, et al.10 identified functional limitations in the SCI population associated with several broad areas. The study surveyed 41 clients with SCI in the early stage of recovery for their perceived level of satisfaction and performance in these areas. The top five identified areas of concern were: functional mobility, including transfers and wheelchair use (19%); dressing (13%); grooming (11%); feeding (8%); and bathing (7%). One of the most common barriers for a neurological hand is spasticity. In a survey of over 500 stroke survivors, 58% experience spasticity, and only 51% of those with spasticity have received treatment.12 Spasticity can be difficult to manage and has the potential to sabotage recovery. First, it is important to determine whether a client’s spasticity is already being managed by oral medication (muscle relaxer or antispasmodic), such as, but not limited to, Baclofen, Zanaflex, Flexeril, Valium, or Dantrium,13,14 Botoxinjections, or the intrathecal baclofen pump (ITB).14 Second, it is important to understand the client’s routine with oral medication and/or Botoxinjections. In a perfect world, a client has a consistent relationship with the physician (physiatrist or neurologist) managing his spasticity in order to monitor the effectiveness of the intervention(s). However, it is not uncommon for the therapist to encourage a client to seek spasticity management or suggest to a client’s physician more comprehensive tone management. Spasticity is known to develop and/or change over weeks, months, or years after a brain injury,15 which when left undiagnosed or undermanaged can lead to debilitating UE changes. Unmanaged spasticity interferes with successful functional use of the affected UE,15 increasing the odds of developing patterns of learned nonuse that may become extremely difficult to overcome. In cases where a client’s spasticity is being managed by an intervention(s), it is worthwhile to discover the client’s dosage amount and routine for oral medication or ITB therapy, when his last series of injections occurred, and when his next series of Botox injections are to occur. Understanding a client’s routine with his spasticity intervention promotes optimal results in therapy. Botox injections, for example, are usually received every 3 to 4 months with the first noticeable effects typically occurring within the first 2 weeks of injections.16 If a client is seeking therapy toward the end of his injection cycle, intervention may result in less desirable outcomes. An oral medication or ITB dose schedule is important to understand, because the best results may be achieved soon after receiving a dose. Some ITB dose schedules can be programmed to correlate with a client’s treatment schedule and/or times of the day when he is most functional. Therapy following a dose of oral medication may offer positive results in reducing spasticity to benefit intervention; however, these muscle relaxers may also have the negative side effect of decreasing a client’s ability to remain alert and attentive to therapy. Since a primary focus of acute rehabilitation following brain injury is ADL performance, inclusion of the affected hand is dependent on how well it can contribute to function. How to involve the affected UE as an assist in self-care is addressed later in this chapter. The challenge at this level of care is balancing the focus of increasing a client’s independence in self-care and addressing the recovery of the affected UE. If paralyzed, inclusion of the affected hand in self-care is limited; training a client to dress, shower, complete toilet hygiene, and so on, will often rely on unilateral techniques. If a neurological hand’s deficits are limited to decreased FMC, encouraging a client to continue utilizing his hand as either his dominant hand or as an equal assist during fine motor activities is important. Humans are inclined to find the most efficient and effective method of completing a task to conserve energy.17 If the less affected hand can complete a task faster with better quality, or if a client has not experienced adequate success in utilizing his affected hand, he may passively accept a unilateral UE existence.13 And the beginning of learned nonuse could commence as early as this stage in recovery. Points to consider and comments for clients and family at the acute stage: 1. Encourage functional use and inclusion of the affected UE in daily activities. Neuroscientists have discovered a “use it or lose it” phenomenon in brain cells during development and in adult brains with stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and other motor neuron diseases.18 2. Develop the mantra: “Repetition, repetition, repetition, with variety.” Research on motor learning has revealed repetition in random practice format (that is, repetition of specific tasks with variability in sequence) is better than a blocked practice format (that is, repetition of the same task) within a treatment session.13 Otherwise known as motor variability, or repetition without repetition,19 this concept suggests the movements required for a specific task (such as, tying shoes) need high repetition in a variety of contexts in order to promote more successful conversion of the actual task. In other words, clients need lots of practice to learn/relearn how to use their affected hand in functional tasks. 3. Emerging movement will likely appear different than movement at a client’s level of function before the injury. As movement returns, clients may have a difficult time figuring out how to use their affected hand,13 or are deterred from using their affected hand because the emerging movement does not appear familiar. For example, clients knew how to tie their shoes prior to their injury, and likely did so without thinking of the movement required by their hands to complete the task. As they attempt familiar tasks (such as, tying shoes) after their injury, their affected hand may not be able to contribute as expected. Assisting clients in recognizing what they see now is only a beginning, and though their movements may not appear the same, different movement patterns can be used, albeit short- or long-term, to complete a task. 4. Be cautious when discussing expectations of recovery. Clients have reported hearing comments from health care professionals that caused them to believe there is no hope for recovery. This leaves a lasting impression that can deter clients from working on their hands and contribute to a negative attitude about their hands. We have seen clients who started out with a non-functional hand in the acute stage have discharged from outpatient therapy writing and typing with their affected hand. 5. Dispel the theory that recovery plateaus within the first 6 months of injury. One study involving brain imaging of chronic stroke survivors revealed improvement in function correlated with increased activity in multiple areas of the brain.22 Studies such as this support plasticity occurs even in the later stages of recovery. Furthermore, a client’s ability to capitalize on returning movement may not occur for a long time post injury. For instance, having the ability to plan and realize variance in movement, such as how to incorporate a lateral pinch in daily activities where a tip-to-tip pinch was formally used, can take time for the client to discover and the brain to problem-solve. 6. ROM, positioning, and orthotic needs can be addressed at this stage with correlating client/family/health care worker education on techniques and how to progress matters, such as an orthotic wearing schedule.13 Clients and families need to know how to don/doff the orthosis, how to care for an orthosis, and the signs of improper fitting. Posting signs with instructions and pictures to assist health care employees to adhere to a positioning and/or orthotic routine may be necessary. 7. Educate clients and families on spasticity (if applicable) and encourage consistent contact with a physician to manage their tone. One study involving transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) noted subjects experienced increased speed and functional ability to complete tasks with the affected UE after bilateral training.24 This was accompanied by a significant increase in corticomotor representation of the involved limb within the affected hemisphere. For more details on bilateral training, see the “Tips from the Field” section later in this chapter. In many cases, emerging motor and/or sensory return occurs in this stage. Although there may still be lingering associated concerns to address, a more intent focus to rehabilitate the hand can begin. Ideally, a client arrives with an assigned neurologist and/or physiatrist, in possession of a resting hand orthosis, and with his spasticity managed (if applicable). If not, these areas need to be addressed in addition to functional return of the hand. Clients may arrive to outpatient therapy making statements, “I want my hand back,” or “When I get my hand back, I will…” Family members may also press for therapy to “fix [the client’s] hand.” Providing realistic feedback is a balance between keeping a client motivated while also preparing him for the potential fact his functional return will not likely be at 100% prior level of function (PLOF). Of course, variability in recovery exists depending on the severity of injury.25 Regardless, it is important to stress that the neurological hand has the potential to continue making improvement. As clients start noticing other clients and the difference between hand presentations, it is important to also remind them that not every injury is the same. As a therapist, comparing clients can be both a benefit and a hazard; it can be beneficial as one prepares for the hand’s progression, and it can be a hazard if it limits a therapist’s approach at treating the neurological hand. Clients may also wonder why their affected lower extremities (LE) are making greater progress than their hand. It may be a benefit to educate them on the location of their stroke, the motor homunculus, and how the UE is typically more involved than the LE following an injury, such as a CVA.26 Additional points to consider and comments for clients and family at the acute stage: 1. No two neurological conditions are alike.1 This is important to realize, because they may compare themselves to other clients. 2. Recovery of function takes time, practice, and commitment. Remind clients that they did not learn how to tie their shoes from one attempt. Consider timing them to provide realistic feedback of their efforts, because clients will often feel as though a task took “forever,” when, in fact, it may have only taken a couple minutes. 3. Promote self-learning with the client and encourage him to try tasks that he may not expect to be able to do. When a client figures out how to accomplish a difficult task on his own, there is greater potential for carryover outside of therapy. 4. Clients need to be successful. Plan activities for that “just right challenge” and grade accordingly in order to promote success. Whichever direction is required to grade an activity for successful results, client engagement is essential in realizing his hand’s potential. 5. Encourage realistic short-term goals. When faced with goals such as, “I want to play my classical guitar again,” stated by a client with trace digit movement 4 months after a stroke, it is important to avoid dismissing the goal. Instead, return with a comment such as, “That is a good long-term goal. Here is where your hand is now, and in order to achieve your long-term goal, we will need to achieve this short-term goal first.” 6. Be positive and supportive when a client incorporates his affected hand in daily activities. Clients can be their own worst critic, because the functional return of their affected hand may not appear the same at PLOF. Providing positive feedback may assist in increasing their confidence to utilize their affected hand with greater consistency. 7. Identify patterns of learned nonuse and tenaciously seek ways to include the affected hand as a functional assist to break these patterns. The earlier learned nonuse habits can be broken, the better. Consider reviewing a constraint protocol if appropriate, or introducing a tool, such as the motor activity log (MAL), without full implementation of a constraint protocol to help clients identify functional activities in which to incorporate their affected UE. 8. Respect the former role of the affected hand. Asking clients to complete activities with their affected, less dominant hand that would otherwise be performed by their dominant hand is not likely to be received well by the client. 1. It is important to reiterate that clients can regain function several years post injury. 2. Since learned nonuse patterns have the potential to be well-ingrained in chronic survivors, it may be beneficial to focus on bilateral UE tasks, because this may encourage more automatic use of their affected hand during functional tasks. 3. In cases of learned nonuse, encourage a client to identify a specific number of tasks for which his affected hand can complete on a regular basis as a starting point for automatic use in functional activities. For example, have a client agree to use his affected hand to carry objects during mobility or stabilize objects as a support for the less affected UE. For clients diagnosed with progressive conditions, such as PD, MS, or other conditions that contribute to declining FMC skills or grip and pinch effectiveness, the focus of therapy can differ. This depends on severity of fine motor deficits, length of time from initial diagnosis and/or appearance of first symptom, and comorbid issues, such as arthritis, decreased sensation, fatigue, and decreased cognitive skills. The length of time from initial diagnosis or appearance of first symptom is not necessarily a predictor of fine motor performance or response to techniques involving recovery of function, because these conditions often have variability in presentations. Therefore, it is important to evaluate and treat each client with a progressive condition on an individual basis and focus on his fine motor skills with respect to function (that is, buttoning, writing, typing, meal preparation, feeding, grooming, and so on). One study indicated a positive response to modified Constraint Induced Therapy (mCIT) on behalf of clients with PD in Hoehn and Yahr stages II to III as demonstrated by improvement in action research arm test (ARAT), FMA, and box and block test (BBT) scores.27 Of particular interest is the finding that bradykinesia may be reduced through mCIT activities. However, a significant limitation in this study is the fact the researchers did not assess functional performance in daily activities. Therefore, they could not infer their results lead to increased or more effective use of the affected hand(s) in daily activities that require fine motor skills. In both MS and PD, research has shown that the more chronic and severe the symptoms, the more difficulty a client will have with dexterity.28,29 This results in clients requiring more assistance and modification to tasks involving dexterity.28 Barriers to completing tasks that involve FMC for individuals with PD include, but are not limited to: tremors, decreased initiation of movement or freezing, weakness in pinch and grasp, medication “off-time,” and decreased attention to tasks (particularly when out of their visual field).1 People with PD respond well by completing movement with high amplitude and high effort.30 Though anecdotal, clients report increased ease in fine motor activities (such as, handwriting or buttoning) when prior to initiating these tasks, they sit with increased trunk extension and “activate” their hand by completing high amplitude “finger flicks.” Barriers for individuals with MS include, but are not limited to: fatigue, weakness in pinch and grasp, decreased sensation, and decreased attention.1 Research is limited with respect to individuals with MS recovering lost function. Therefore, therapy should focus on preserving existing skills through fine motor exercises and consistent use in meaningful activities while educating clients to avoid fatigue. Points to consider and comments for clients and family with progressive conditions: 1. Time of day may impact effectiveness of dexterity, because medication regimes, level of alertness, or degree of fatigue may correlate with performance. Try to organize tasks with high dexterity demands with times of the day when performance has its best potential. 2. Though recovery of lost function may not be attainable for clients with more chronic and severe symptoms, modification and adaptation may assist in increasing a client’s participation in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) tasks that require dexterity, while decreasing dependence in caregiver support. 3. Encourage upright posture and “finger flicks” prior to engaging in (and throughout as needed) fine motor tasks for people with PD. 4. Promote tasks that accentuate existing fine motor skills in order to preserve the current level of functional ability. This may decelerate disease progression and reduce caregiver burden over the long-term. 5. Respect to what degree a client utilizes dexterity skills throughout his daily routine and promote realistic functional goals for the client and family. For example, a client with PD who also possesses concomitant cognitive, FMC, and motor planning deficits can preserve independence in feeding through increased availability of finger-foods. In severe cases involving cognitive and motor planning deficits, utensil management can often be frustrating, and training these clients to use adaptive equipment (AE) may not lead to successful outcomes.

The Neurological Hand

Timeline of Intervention

Spasticity

The Hemiplegic/Hemiparetic Hand per Stage of Recovery

Acute Stage (Initial Injury up to Discharge from Hospital/Inpatient Rehabilitation)

Post-Acute Stage (After Release from Hospital/Inpatient Rehabilitation, Up To 12 Months Post-Injury)

Chronic Stage (12 Months or Longer Post-Injury)

Progressive Conditions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine