16 The forearm, wrist, and hand

So much in everyday life depends upon the efficient working of the hand, and so great is the practical and economic consequence of its disablement, that the care of the diseased or injured hand has become one of the most vital branches of orthopaedic surgery. It is also one of the most fascinating.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF FOREARM, WRIST, AND HAND COMPLAINTS

Steps in clinical examination

A suggested routine of clinical examination is summarised in Table 16.1.

Table 16.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the forearm, wrist, and hand

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE FOREARM, WRIST, AND HAND | |

| Inspection | |

| Bone contours | Metacarpo-phalangeal joints— |

| Soft-tissue contours | Flexion–extension; adduction– |

| Colour and texture of skin | abduction |

| Scars and sinuses | Interphalangeal joints—Flexion–extension |

| Palpation | Power |

| Skin temperature | Power of each muscle group in control of: |

| Bone contours | |

| Soft-tissue contours | |

| Local tenderness | |

| Movements (active and passive) | Stability |

| At the wrist: | Tests for abnormal mobility |

| Radio-carpal joint—Flexion–extension; adduction–abduction | Nerve function |

| Inferior radio-ulnar joint—Supination and pronation | Tests of sensory function, motor function, and sweating in distribution of median, ulnar, and radial nerves |

| At the hand: | Circulation |

| Carpo-metacarpal joint of thumb—Flexion–extension; adduction–abduction; opposition | Arterial pulses, warmth and colour, capillary return, cutaneous sensibility |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POSSIBLE EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF FOREARM AND HAND SYMPTOMS | |

| This is important if a satisfactory explanation for the symptoms is not found on local examination. The investigation should include: | |

| 3. GENERAL EXAMINATION | |

| General survey of other parts of the body. The local symptoms may be only one manifestation of a more widespread disease | |

Movements at the wrist

Like the elbow, the wrist comprises two distinct components:

The movements at each component must be examined independently.

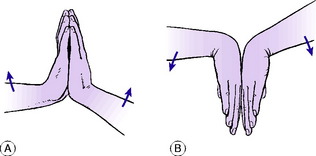

A rapid and reasonably accurate method of comparing the range of flexion– extension movement on the two sides is as follows: To judge the range of extension: The patient places the palms and fingers of the two hands in contact in the vertical plane and lifts the elbows as far as he can while keeping the ‘heels’ of the hands together (Fig. 16.1). The angle between hand and forearm is easily compared on the two sides. To judge the range of flexion the manoeuvre is reversed. The patient places the backs of the hands together, with the fingers directed vertically downwards, and lowers the elbows as far as he can (Fig. 16.1). The angle between hand and forearm is compared on the two sides.

The inferior radio-ulnar joint. The normal range is 90 ° of supination and 90 ° of pronation. To determine the range accurately the patient’s elbows must be flexed to a right angle in order to eliminate rotation at the shoulder (see Fig. 15.1).

Movements of the hand

Movements of the hand occur mainly at three groups of joints:

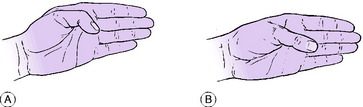

Carpo-metacarpal joint of thumb. This joint allows movement in five directions: flexion, or movement of the thumb metacarpal medially in the plane of the palm; extension, or movement of the thumb metacarpal laterally in the plane of the palm; adduction, or movement of the metacarpal towards the palm in a plane at right angles to it; abduction, or movement of the metacarpal away from the palm in a plane at right angles to it; and opposition, or rotation of the metacarpal to bring the thumb nail into a plane parallel with the palm (Fig. 16.2).

Power

Test the power of each movement in turn. In the hand this examination demands considerable patience, for each muscle group must be tested individually. Thus in the thumb it is necessary to test the abductors, the adductor, the extensors (longus and brevis), the flexors (longus and brevis), and the opponens. In the fingers test the flexors (profundus and superficialis), the extensor digitorum and extensor indicis, the interossei and the lumbricals. Grip: Test the power of grip, which demands the combined action of the flexors and extensors of the wrist and the flexors of the fingers and thumb.

Nerve function

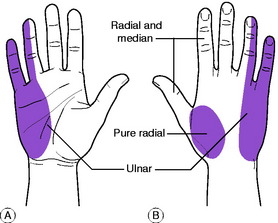

The state of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves is determined by tests of sensory function, motor function, and sweating. The ulnar nerve normally supplies sensation to the ulnar side of the hand together with the little finger and half the ring finger (Fig. 16.3).

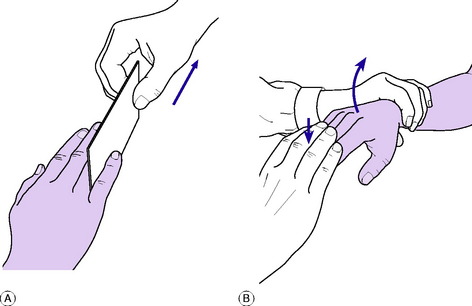

The remainder is largely innervated from the median nerve with some overlap on the dorsum of the hand from the radial nerve (Fig. 16.3). Only a small skin area at the base of the thumb is purely supplied by the radial nerve. Intact function of the median nerve is indicated by ability to oppose the thumb to the little finger (see Fig. 16.2). Intact ulnar nerve function is shown by ability to spread the fingers apart and to bring them together again to grip a card between the middle and ring fingers (Fig. 16.4). An index of radial nerve function is the ability to extend the thumb and to extend the fingers at the metacarpo-phalangeal joints.

Circulation

The state of the circulation is assessed from the condition of the arterial pulses, the warmth and colour of the digits, the capillary return at the nail beds, and cutaneous sensibility. It should be remembered that sensibility to touch in the fingers is a most useful index of the adequacy of the circulation. Nerves require a blood supply to enable them to conduct impulses, and if the circulation is interrupted sensibility is quickly lost.

DISORDERS OF THE FOREARM

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of acute osteomyelitis, p. 85)

Acute osteomyelitis is rather uncommon in the forearm bones. As in other sites, the infection may be blood-borne (haematogenous) or it may be introduced from without, usually in consequence of a compound fracture. The haematogenous type occurs mainly in children. It affects the radius more often than the ulna, and the lower metaphysis rather than the upper (see Fig. 7.3B).

The clinical features and treatment are like those of acute osteomyelitis elsewhere.

CHRONIC OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of chronic osteomyelitis, p. 90)

As in other bones, chronic osteomyelitis of the radius or ulna follows an acute infection.

BONE TUMOURS IN THE FOREARM AND HAND

Benign tumours (General description of benign tumours of bone, p. 106)

Chondroma

Enchondroma, which grows within the bone and expands it, is prone to occur in the metacarpals and phalanges of the hand presenting with deformity or pathological fracture. The tumour may be solitary, but in the condition of multiple enchondromatosis, or Ollier’s disease, the tumours may affect many bones in the hand causing ugly swelling and deformity of the fingers (Fig. 16.5). Malignant transformation is hardly known in a solitary chondroma of a bone of the hand, but it is a possibility in cases of multiple enchondromatosis, leading to chondrosarcoma.

Treatment. If small, the tumour should be treated expectantly and fractures normally heal with simple splintage. Operation is required only if the tumour is found to be enlarging. Large tumours should be excised and sent for routine histological examination, the bone substance being restored by cancellous bone grafts.

Enchondromas of long bones are less common in the forearm, though these bones may be affected by multiple osteochondroma in the hereditary condition of diaphyseal aclasis (p. 63). These tumours may interfere with the normal growth of the affected bone resulting in shortening and deformity.

Giant-cell tumour (osteoclastoma)

The lower end of the radius is one of the common sites in the upper limb for the development of a giant-cell tumour, which though classed as benign may show invasive tendencies. The lower end of the ulna is also susceptible. The tumour extends into the former epiphysial region close up to the articular surface (Fig. 16.6).

Treatment. If the tumour is in the lower end of the radius radical excision and replacement by a suitable bone graft is to be recommended. A graft obtained from the upper part of the fibula is suitable because its shape matches that of the original bone. Ideally, the graft should be taken with the supplying artery and veins, which are anastomosed to suitable vessels in the recipient area by a microsurgical technique. If the lower end of the ulna is the part affected the bone should be excised up to a point well proximal to the tumour. The resulting disability is negligible.

VOLKMANN’S ISCHAEMIC CONTRACTURE1

Cause. It is caused by ischaemia of the flexor muscles, brought about by injury to, or obstruction of, the brachial artery near the elbow; or by tense oedema of the soft tissues of the forearm constrained within an unyielding fascial compartment.

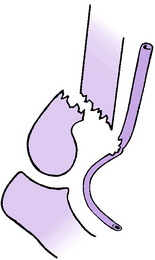

Any major fracture in the elbow region or upper forearm may lead to arterial occlusion. That most commonly responsible is a supracondylar fracture of the humerus with displacement, the brachial artery being severed or contused by the sharp lower end of the main shaft fragment (Fig. 16.7). Contusion alone is sufficient to interrupt the flow of blood, because the artery goes into spasm and its lumen may be occluded by thrombosis.

In some cases the cause of the vascular obstruction is an over-tight plaster or bandage.

On examination in the incipient stage, the fingers are white or blue, and cold. The radial pulse is absent. Active finger movements are weak and painful. Passive extension of the fingers is especially painful and restricted. There may or may not be evidence of interruption of nerve conductivity – namely, anaesthesia of the fingers and paralysis of the small muscles of the hand.

In the established condition, which develops gradually within a few weeks of the injury, there is a striking flexion contracture of the wrist and fingers, from shortening of the fibrotic forearm flexor muscles (Fig. 16.8). Sensory and motor paralysis of the hand may persist as complicating factors, but they do not form an essential feature of Volkmann’s contracture as such.

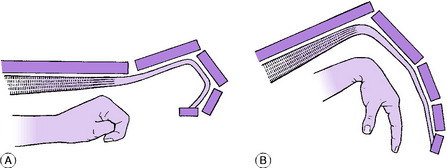

Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture bears no real resemblance to Dupuytren’s contracture (p. 321), for it affects the wrist as well as all the joints of the fingers, and there is no palpable thickening in the palm. Moreover the contracture is demonstrably brought about by shortening of the flexor muscles, because if the wrist is flexed passively to relax the flexor tendons the range of extension at the finger joints is increased. Conversely, if the tendons are relaxed by flexing the fingers fully the range of wrist extension is increased (Fig. 16.9).

First step. All splints, plaster, and bandages that might be obstructing the circulation are removed. In the case of a fracture, gross displacement of the fragments is corrected as far as possible by gentle manipulation and a well-padded plaster splint is applied. Likewise if the elbow is dislocated it must be reduced without delay. Heat cradles or hot bottles are applied over the other three limbs and trunk to promote general vasodilation.

ARTICULAR DISORDERS OF THE WRIST AND HAND

MADELUNG’S DEFORMITY1 (Radio-ulnar dyschondrosteosis)

Madelung’s deformity (radio-ulnar dyschondrosteosis) is a congenital subluxation or dislocation of the lower end of the ulna, from malformation of the bones. Although it is seemingly a localised disorder there may be minor generalised abnormalities of bone structure, often with short stature.

The deformity varies in degree from a slight prominence of the lower end of the ulna at the back of the wrist, to complete dislocation of the inferior radio-ulnar joint with marked radial deviation of the hand (Fig. 16.10). The more severe types of deformity may be associated with congenital absence or hypoplasia of the radius.

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE WRIST AND HAND (General description of pyogenic arthritis, p. 96)

Pyogenic arthritis of the wrist is uncommon. Infection may be haematogenous, or it may be introduced through a penetrating wound. Spread from a focus of osteomyelitis is rare, partly because osteomyelitis itself is uncommon in the forearm bones, and partly because the lower metaphysis of the radius is entirely outside the capsule of the joint. (The lower metaphysis of the ulna is partly intracapsular (see Fig. 7.2).)

The clinical features and treatment of pyogenic arthritis are similar to those at other sites.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE WRIST AND HAND (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

Rheumatoid arthritis commonly affects the wrists and hands and is a major cause of serious loss of function and of ugly deformity. Usually many or all of the joints of the hand are affected, though occasionally the disease may begin in a single joint. Affected joints are swollen from synovial thickening, and movement is restricted. In the later stages articular cartilage and the underlying bone are eroded, and the fingers tend to deviate medially (‘ulnar drift’), with dorsal prominence of the metacarpal heads and characteristic visible deformity (Fig. 16.11A). At the wrist joint the disease commonly results in dorsal subluxation and dislocation of the ulnar head accompanied by subluxation of the carpus on the radius and radial deviation of the hand. Radiographs do not show any abnormality at first. Later, there is diffuse rarefaction of the bones. Later still, in progressive disease, destruction of cartilage leads to narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 16.11B), and the subchondral bone may be eroded.

Rupture of tendons. Both the extensor and the flexor tendons are liable to spontaneous rupture, from softening or fraying where they lie within inflamed synovial sheaths. The extensor pollicis longus, extensor digitorum, and extensor digiti minimi are the tendons that most commonly rupture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree