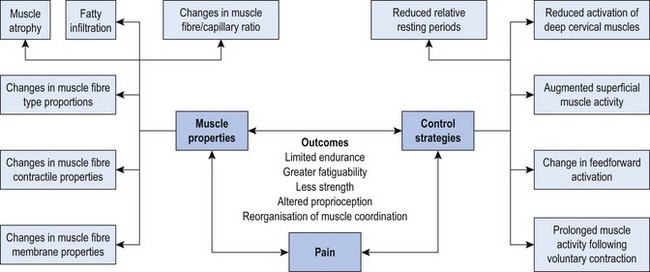

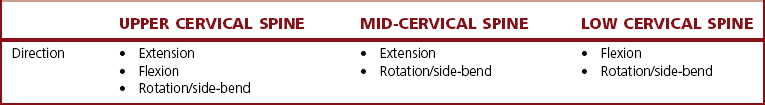

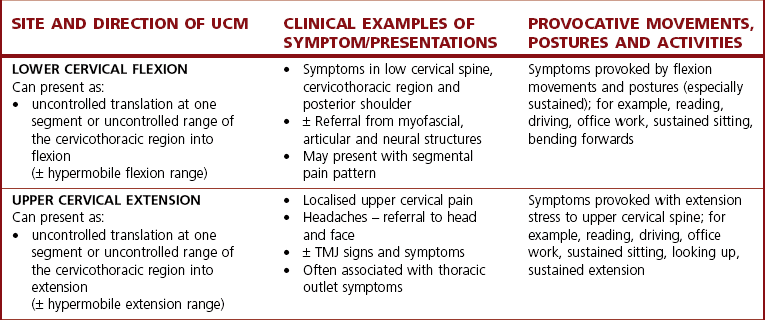

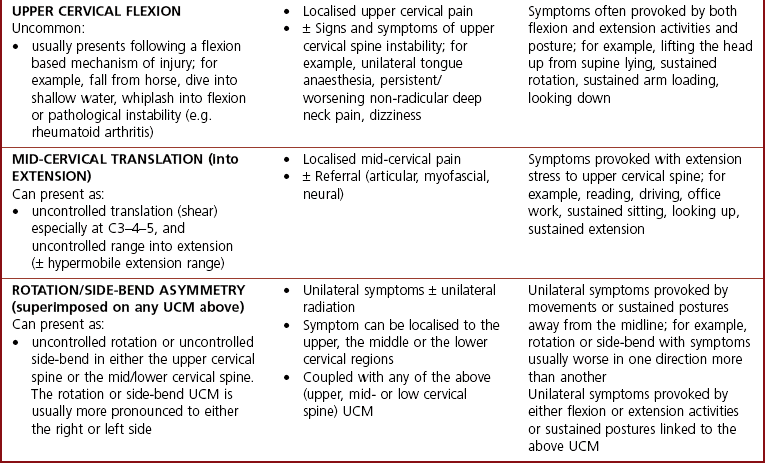

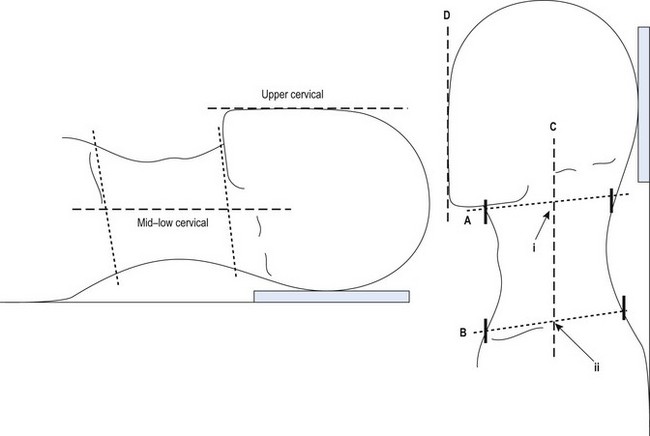

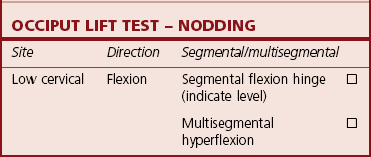

Chapter 6 Upper cervical flexion control Upper cervical extension control Mid-cervical translation (during extension) control Low cervical side-bend control Upper cervical side-bend control In the past two decades there has been an increase in research into cervical musculoskeletal disorders with many movement impairments and pathophysiological disorders subsequently identified. These include changes in the sensory and motor systems, in sensorimotor function and psychological features associated with whiplash, headache and neck pain (Jull et al 2008). Although the management of neck pain does include the assessment and retraining of muscle function, assessment of dynamic movement faults, known to be a significant factor in musculoskeletal disorders, are still poorly described, utilised and researched in the cervical spine (Jull et al 2008). Fritz & Brennan (2007) have highlighted the importance of developing a classification system for subgroups of patients with neck pain. This chapter sets out to explore the assessment and retraining of uncontrolled movement (UCM) in the cervical spine. Before details of the assessment and retraining of UCM in the cervical region are explained, a brief review of cervical spine structure and function, changes in muscle function and movement and postural control in the region are presented. The cervical spine supports and orients the head in space relative to the thorax (Jull et al 2008). To do this effectively and efficiently the cervical muscle system, comprising both deep and superficial muscles, must work in synergy and provide the movement and stability. The ‘stability system’, characterised by deep segmentally attaching muscles, should be able to maintain control of the cervical spine segments during low load postural control tasks, functional movements and high load fatiguing activities. The co-activation of the stability muscles should control abnormal intersegmental translation at the motion segments, give segmental support to the spinal neutral curves, maintain the head balance on the upper cervical spine and dynamically balance the head and neck on the trunk. The anatomical connections between the cervical spine, temporomandibular joint (TMJ), thorax and shoulder girdle, with the musculoskeletal and neurovascular structures, make movement control function complex. Further influences come from respiratory function. There is evidence to demonstrate changes in cervical and scapulothoracic muscle function in people with neck pain. Falla & Farina (2007) describe in detail the altered control strategies and peripheral changes in cervical muscles in people with pain which lead to limited endurance, greater fatiguability, less strength, altered proprioception and reorganisation of muscle coordination. Figure 6.1 illustrates the interrelationships between pain, altered control strategies and peripheral changes in the cervical muscles (Falla & Farina 2007). Similarly, recruitment of the scapulothoracic muscles has been identified in people with neck pain (Nederhand et al 2000; Falla et al 2004b; Szeto et al 2005a; Johnston et al 2008b; Szeto et al 2008) along with histological changes in upper trapezius (Lindman 1991a, b). The current literature suggests people with cervical pain have altered movement control strategies and that these changes are associated with pain and disability (Falla et al 2004b; Johnston et al 2008a, b). Altered movement strategies have been associated with the clinical presentations of whiplash (Nederhand et al 2002; Jull et al 2004; Sterling et al 2003, 2005), cervicogenic headaches (Jull et al 2002; Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al 2008), neck pain (Jull et al 2004; O’Leary et al 2007; Falla et al 2004a, b) and work-related musculoskeletal disorders (Johnston 2008a, b; Szeto et al 2008). The pathophysiological and psychosocial mechanisms identified in people with neck pain are proposed to be a cause of respiratory disorders (Kapreli et al 2008). These altered strategies will influence the control of movement which can present as both uncontrolled translatatory movement and uncontrolled range or physiological motion. Either movement dysfunction will present clinically as areas of relative flexibility. Increases in translational movements have been highlighted at C4–5 and C5–6 in people with disc degeneration (Miyazaki et al 2008). With disc degeneration the intersegmental motion changes from the normal state to an unstable phase and subsequently to an ankylosed stage with increased stability and loss of function in late stage degeneration. Further literature indicates how alteration in the cervical motion is seen at segmental levels in subjects with neck pain (White et al 1975; Amevo et al 1992; Panjabi 1992; Singer et al 1993; Dvorak et al 1998; Cheng et al 2007; Grip et al 2008). Changes in alignment in the cervical spine may result in a forward head posture position demonstrating an increase in low cervical flexion (Szeto et al 2005b; Falla et al 2007; Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al 2007; Straker et al 2008). Yip and colleagues (2008) noted the greater the forward head posture, the greater the disability. Regions and segments of less mobility have been noted in the cervical spine which will present clinically as regions of relative stiffness (Dall’Alba et al 2001, Dvorak et al 1988). Systematic reviews indicate that different treatment modalities have an effect on neck disorders with exercise being a key element in the management of pain disability and dysfunction (Kjellman et al 1999; Gross et al 2004; Verhagen et al 2004). In addition, there is a growing body of evidence that supports the efficacy of exercise in the management of cervical pain (Jull et al 2002; Falla et al 2006, 2007). Along with the identification and correction of movement control dysfunction, it is important to address the altered control strategies and peripheral changes in the cervical muscles (Jull et al 2008, ch. 4 p. 50). Psychosocial and physiological factors also have a role in the development and maintenance of cervical pain (Jull et al 2008, ch. 7 p. 97) and influence how it is managed appropriately. It is important to consider other postural influences when retraining the control of neck movements as it has been demonstrated that there is better recruitment of postural neck muscles with facilitation of a good lumbar position (Falla et al 2007). Researchers have further demonstrated that improving postural alignment of the thoracic spine and the head and neck also has benefits for recruitment of the deep neck stability muscles. Changes in muscle function have been identified in functional activities, highlighting the importance of linking the rehabilitation of movement control with functional activities (Falla et al 2004b; Szeto et al 2008). This body of evidence indicates it is important to be able to identify control impairments in people with neck pain and relate these to their symptom presentation and disability. The classification in terms of site and direction of UCM has been proposed (Mottram 2003; Comerford & Mottram 2011), and a diagnosis based on movement impairment (Sahrmann 2002; McDonnell et al 2005; Caldwell et al 2007). The influence of the scapula on neck symptoms and range of movement needs to be considered in treating UCM in the cervical spine. Passive scapula elevation has been shown to decrease neck symptoms and increase range of movement (Van Dillen et al 2007). This chapter details the assessment of UCM at the cervical spine region and describes retraining strategies. The diagnosis of site and direction of UCM at the cervical spine can be identified in terms of site: upper cervical spine, mid-cervical spine and lower cervical spine, and direction of flexion, extension and asymmetry (Table 6.1). As with all UCMs, they can present as uncontrolled translational movements (e.g. at C4/5 (Cheng et al 2007)) or uncontrolled range movements (e.g. low cervical flexion (Straker et al 2008)). The site and direction of UCM at the cervical spine can be linked with different clinical presentations, postures and activities aggravating symptoms. The typical assessment findings in the cervical spine are identified in Table 6.2. The key principles for assessment and classification of UCM have previously been described in Chapter 3. All dissociation tests are performed with the cervical spine in the neutral training region. See Figure 6.2. Visualise a line across the upper neck (A), which follows the line of the jaw towards C2. Bisect this line (i). Visualise a second line across the lower neck (B), which follows the line of the clavicle towards the cervicothoracic junction. Bisect this line (ii). A line (C) that joins the bisectors (i) and (ii) ideally should be vertical in standing and sitting or horizontal in lying or within 10° of forward inclination. See Figure 6.2. Visualise a line in the plane of the face (D). This line ideally should be parallel to or within 10° of the low cervical neutral line (C). The cervical spine neutral position needs to be observed with consideration of thoracic and lumbar postures in sitting, standing and functional positions as one region may influence another (Straker et al 2008). Cervical postural dysfunction is frequently most evident in sitting, but both sitting and standing will often demonstrate significant lumbopelvic alignment abnormalities, which may influence cervicothoracic alignment. Facilitation of lumbopelvic and thoracolumbar neutral alignment may well change cervical posture. It is important to consider the positions of symptom provocation in function. Resting posture is individual, and people with restrictions may not present with an ‘ideal’ resting position. Instead, they present with a resting or ‘natural’ alignment that reflects how they have adapted to their restrictions. For example, if someone has a marked restriction of low cervical extension, they may develop a head forward posture as they adaptively find a mid-point within the available neutral region (somewhere midway between the ends of range). If the attempt to position the low cervical line in an ‘ideal’ neutral results in the low cervical joints being sustained at end range of the restricted extension, it then becomes necessary to reposition the low cervical spine within mid-range; preferably close to the neutral line. Box 6.1 illustrates some clinical pointers which may help the clinician achieve the neutral training position. • Restriction of upper or mid-cervical flexion – the upper/mid-cervical spine maintains the lordosis during flexion. At the end of neck flexion range the cervical lordosis does not flatten or reverse. The restriction may be due to a loss of articular motion or due to a loss of extensibility of myofascial structures. Cervical flexion joint mobility can be tested passively, and passive manual examination will identify any significant articular restriction of segmental flexion range of motion. Posterior myofascial restrictions of flexion can be tested with passive extensibility of the suboccipital extensors, sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitis, levator scapula and the ligamentum nuchae. • Restriction of thoracic flexion– mid- and upper thoracic flexion restriction are not so common, but if present they are easily tested. • Cervicothoracic flexion – the low cervical spine may initiate the movement into flexion; or, during the return to neutral, the head may stay in a head forward position. The posture resulting from this is often described as a cervicothoracic bump or dowager’s hump and may be observed as excessive protuberance or ‘step’ of C6–T1 spinous processes. • Upper cervical flexion – this is uncommon but is usually associated with a traumatic forced flexion incident (requires assessment of upper cervical instability). The person sits tall with their feet unsupported and the pelvis in neutral. The low and upper cervical spine is positioned in the neutral training region. The scapula and TMJ are also positioned in neutral (Figure 6.3). Without letting the head move forwards, the person is instructed to lift the chin into partial upper cervical extension and then to independently flex the upper cervical spine by visualising sliding the occiput vertically up an imaginary wall placed at the back of the head. This should be a nodding action (through a transverse axis of the upper cervical spine, not a chin tuck or retraction action). There should be no low cervical flexion (head moving forwards) or loss of scapula position (observe for scapula elevation, forward tilt or downward rotation). The jaw should stay relaxed (Figure 6.4). Ideally, the person should be able to easily maintain the low cervical spine neutral alignment and prevent the head moving forwards while actively moving the upper cervical spine through range from extension to flexion (chin lift to chin drop) by using a ‘nodding’ action of the head. • If only one spinous process is observed as prominent and protruding ‘out of line’ compared to the other vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a segmental flexion hinge. The specific hinging segment should be noted and recorded. • If excessive cervicothoracic flexion is observed, but no one particular spinous process is prominent from the adjacent vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a multisegmental hyperflexion. Initially, position the lower and upper cervical spine in neutral with the head supported. This can be done in sitting or standing with the thoracic spine and the back of the head against a wall (Figure 6.5). Using the feedback and support of the supporting surface, the person is trained to perform independent upper cervical flexion (nodding). The upper cervical spine can flex only so far as there is no low cervical flexion and the scapulae and TMJ do not lose their neutral position. If control is poor, start in supine lying with the occiput supported on a small folded towel (Figure 6.6). Initially the scapula may need to be supported. As the ability to control upper cervical extension gets easier and the pattern of dissociation feels less unnatural the exercise can be progressed from head and shoulder girdle supported to head and shoulder girdle unsupported postures. A useful progression is performed standing with the forearms vertical on a wall. Keep the scapula in mid-position and push the body and head away from the wall (Figure 6.7). Keeping the head back over the shoulders slowly perform independent upper cervical flexion (nodding) (Figure 6.8). The upper cervical spine can flex only so far as there is no low cervical flexion and the scapulae do not lose their neutral position. The person should self-monitor the control of low cervical flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T29.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T29.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining Once the pattern of dissociation feels familiar it should be integrated into various functional postures and positions. T29.4 illustrates some retraining options. The person should have the ability to actively flex the thoracic spine while controlling low cervical and head neutral. The person sits tall with feet unsupported and pelvis neutral. The low and upper cervical spine is positioned in the neutral training region. The scapula and TMJ are also positioned in neutral. The plane of the face should be vertical (Figure 6.9). Thoracolumbar motion is monitored by placing one hand on the sternum and head and cervical motion monitored by placing the thumb on the jaw and the middle finger on the forehead. Without letting the head move forwards or down (monitor jaw and forehead) allow the sternum to lower (drop) towards the pelvis. Ideally, the person should have the ability to keep the head neutral while independently flexing the thoracic region from a position of extension through to flexion, without any movement of the head. Ideally, the person should be able to perform this dissociated movement without feedback from their hands (Figure 6.10). • If only one spinous process is observed as prominent and protruding ‘out of line’ compared to the other vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a segmental flexion hinge. The specific hinging segment should be noted and recorded. • If excessive cervicothoracic flexion is observed, but no one particular spinous process is prominent from the adjacent vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a multisegmental hyperflexion. The person should self-monitor the control of low cervical flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T30.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T30.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining Once the pattern of dissociation feels familiar it should be integrated into various functional postures and positions. T30.4 illustrates some retraining options. The person should have the ability to actively perform shoulder flexion through full range to the overhead position while concurrently controlling low cervical spine and head neutral. The person stands with the arms resting by the side in neutral rotation (palm in) and with the scapula in a neutral position. The low and upper cervical spine is positioned in the neutral training region. The scapula and TMJ are also positioned in neutral. The plane of the face should be vertical (Figure 6.11). Without letting the head move forwards or look down, the person is instructed to keep the low cervical spine and the head in the neutral position and lift both arms overhead, through full 180° of shoulder flexion, and lower the arms back to the side. The neutral arm rotation (palm in) should be maintained. Ideally, the person should have the ability to keep the head neutral while independently flexing the shoulders and lifting the arms to a vertical overhead position (180° flexion) and lowering them back to the side (Figure 6.12). • If only one spinous process is observed as prominent and protruding ‘out of line’ compared to the other vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a segmental flexion hinge. The specific hinging segment should be noted and recorded. • If excessive cervicothoracic flexion is observed, but no one particular spinous process is prominent from the adjacent vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a multisegmental hyperflexion. Without letting the head move forwards or look down, lift both arms to a vertical overhead position (180° shoulder flexion). The person should keep the head neutral while independently flexing the shoulder. If control is poor, stand with the head and thoracic spine supported against a wall for feedback and support. Start doing unilateral arm lifts (Figure 6.13) and progress to bilateral arm lifts as control improves. Initially reduce the arm load by lifting a short lever (elbow bent) and only through reduced range (e.g. 90° then 120°, etc.). As the ability to independently control movement of the low cervical spine gets easier and the pattern of dissociation feels less unnatural, the exercise can be progressed to performing the exercise to long lever full overhead range against light resistance. An alternative progression is to face the wall with the forearms vertical on the wall. Keep the scapula in mid-position and push the body and head away from the wall (Figure 6.14). Keeping the head back over the shoulders, slowly slide one forearm vertically up the wall (Figures 6.15 and 6.16) only so far as there is no low cervical flexion. The person should self-monitor the control of low cervical flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T31.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T31.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining Once the pattern of dissociation feels familiar it should be integrated into various functional postures and positions. T31.4 illustrates some retraining options. The person sits tall with feet unsupported and pelvis neutral. The low and upper cervical spine is positioned in the neutral training region. The scapula and TMJ are also positioned in neutral (Figure 6.17). The therapist monitors the upper cervical neutral position by palpating the occiput with one finger and palpating the C2 spinous process with another finger (Figure 6.19). During testing, if the palpating fingers do not move, the upper cervical segments are able to maintain neutral. If the palpating fingers move apart, uncontrolled upper cervical flexion is identified. Without letting chin drop or tuck in, the person is instructed to move the low cervical spine through flexion by tilting the head to lean forwards from the base of the neck. The person is to only move through the range where the ability to control the upper cervical spine is effective (Figure 6.18). There should be no upper cervical flexion (palpating fingers move apart or chin drop or tuck is observed) or loss of scapula position (especially observe for scapula elevation, retraction or forward tilt). The jaw should stay relaxed. While teaching, allow the person to initially learn and practise the test movement using feedback from palpation with their own fingers to monitor and control the upper cervical neutral position until awareness of the correct movement is achieved (Figure 6.20). • If only one spinous process is observed as prominent and protruding ‘out of line’ compared to the other vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a segmental flexion hinge. The specific hinging segment should be noted and recorded. • If excessive cervicothoracic flexion is observed, but no one particular spinous process is prominent from the adjacent vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a multisegmental hyperflexion. Initially, in sitting or standing, the thoracic spine and the back of the head should be supported upright against a wall. The low cervical spine is in slight extension. The upper cervical spine is positioned in neutral by actively lifting and dropping the chin through the full range of upper cervical movement, then positioning in the middle of this range. Ideally, the plane of the face should incline forwards about 45° (Figure 6.21). Using feedback from palpating the occiput with one finger and C2 with another finger, the person is trained to perform independent lower cervical flexion. The person should prevent the chin from tucking or dropping and maintain the upper cervical spine neutral (palpating fingers do not move apart) while independently moving the lower cervical spine through range from extension to flexion (head starts upright and leans forwards). The lower cervical spine can flex and the head leans forwards from the base of the neck only so far as there is no upper cervical flexion and the scapula and TMJ do not lose their neutral position. As the ability to control upper cervical extension gets easier and the pattern of dissociation feels less unnatural, the exercise can be progressed from head and shoulder girdle supported to head and shoulder girdle unsupported postures (Figure 6.22). The person should self-monitor the control of low cervical flexion UCM with a variety of feedback options (T32.3). There should be no provocation of any symptoms within the range that the flexion UCM can be controlled. T32.3 Feedback tools to monitor retraining Once the pattern of dissociation feels familiar it should be integrated into various functional postures and positions. T32.4 illustrates some retraining options. The person should have the ability to actively perform shoulder extension through full range while concurrently controlling cervical spine and head neutral. The person stands with the arms resting by the side in neutral rotation (palm in) and with the scapula in a neutral position. The low and upper cervical spine is positioned in the neutral training region. The scapula and TMJ are also positioned in neutral. The plane of the face should be vertical (Figure 6.23). Without letting the chin tuck in towards the neck, or the scapula tilting forwards or retracting, the person is instructed to keep the cervical spine and the head in the neutral position and reach back with both arms, through 15–20° of shoulder extension. The neutral arm rotation (palm in) should be maintained. Ideally, the person should have the ability to keep the head and scapulae neutral while independently extending the shoulders and reaching back with the arms to end range (Figure 6.24). • If only one spinous process is observed as prominent and protruding ‘out of line’ compared to the other vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a segmental flexion hinge. The specific hinging segment should be noted and recorded. • If excessive cervicothoracic flexion is observed, but no one particular spinous process is prominent from the adjacent vertebrae, then the UCM is interpreted as a multisegmental hyperflexion.

The cervical spine

Introduction

Cervical spine muscle function

UCM in the cervical spine

Introduction to rehabilitation for cervical spine dysfunction

Identifying UCM in the cervical spine

Diagnosis of the site and direction of UCM in the cervical spine

Identifying the site and direction of ucm at the cervical spine

Cervical spine neutral: positioning cervical, scapula and temporomandibular neutral

Guideline to assess and reposition low cervical neutral

Guideline to assess and reposition upper cervical neutral

Guideline to assess and reposition temporomandibular joint (TMJ) neutral

Cervical flexion control

Observation and analysis of neck flexion

Movement faults associated with cervical flexion

Relative stiffness (restrictions)

Relative flexibility (potential UCM)

Tests of low cervical flexion control

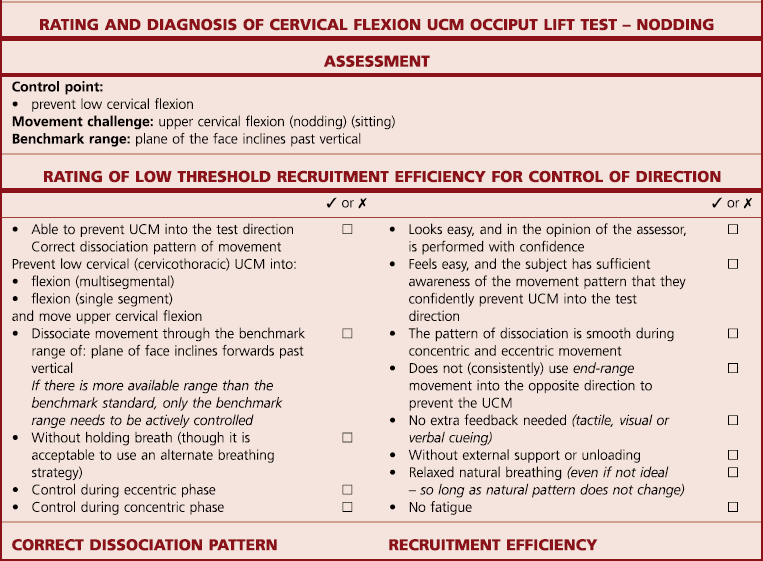

T29 Occiput lift test – nodding (tests for low cervical flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Low cervical flexion UCM

Rating and diagnosis of cervical flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

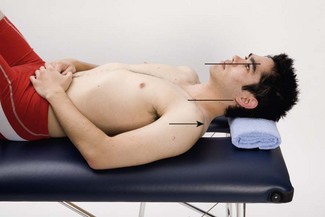

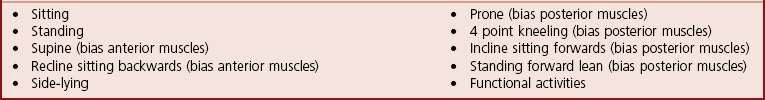

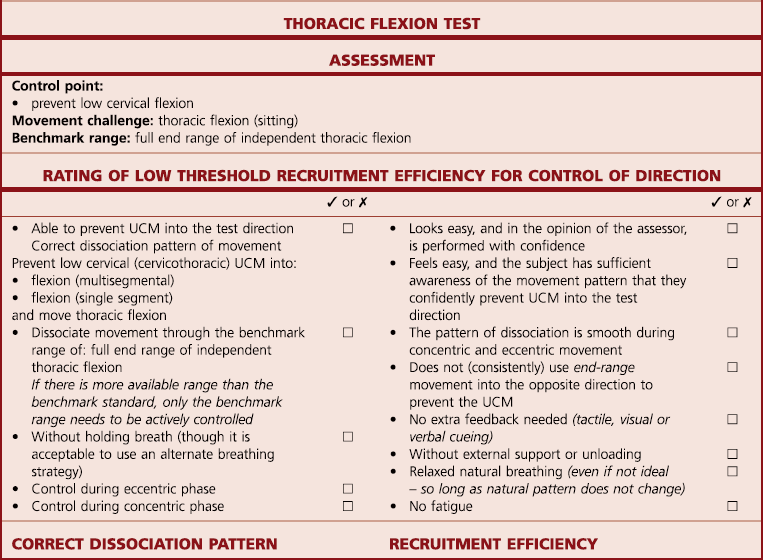

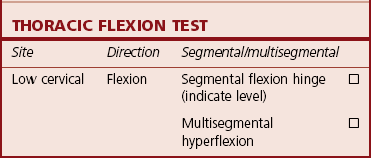

T30 Thoracic flexion test (tests for low cervical flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Low cervical flexion UCM

Rating and diagnosis of cervical flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

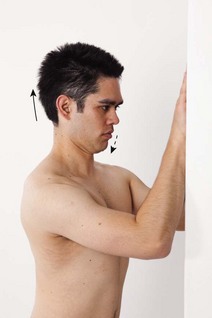

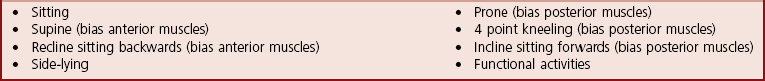

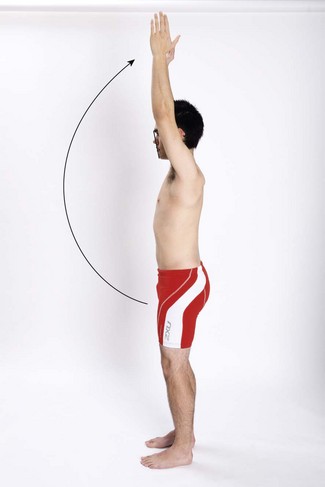

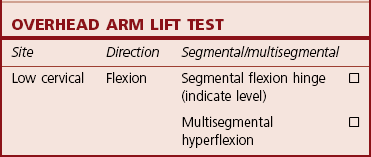

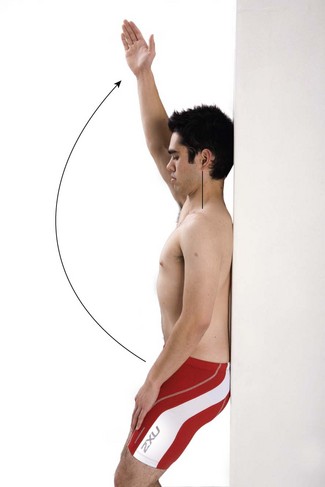

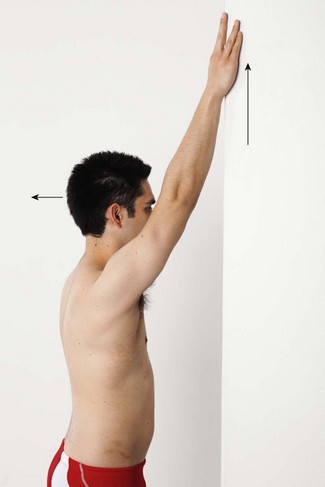

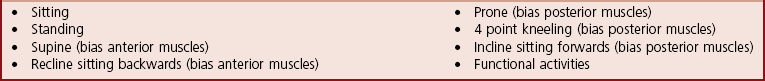

T31 Overhead arm lift test (tests for low cervical flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Low cervical flexion UCM

Rating and diagnosis of cervical flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Adhesive tape

Skin tension for tactile feedback

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

Test of upper cervical flexion control

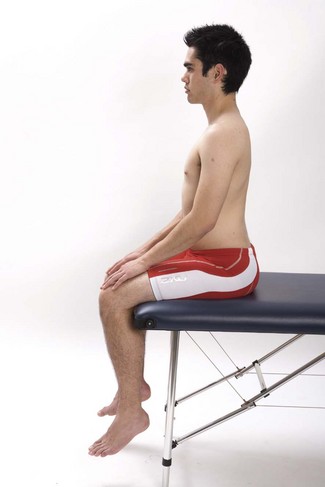

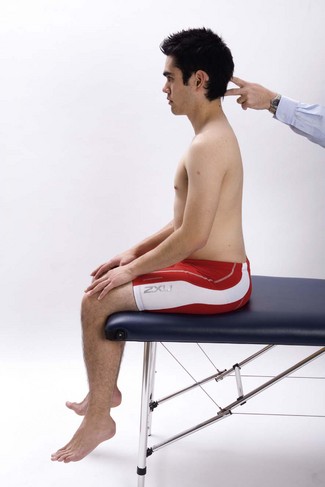

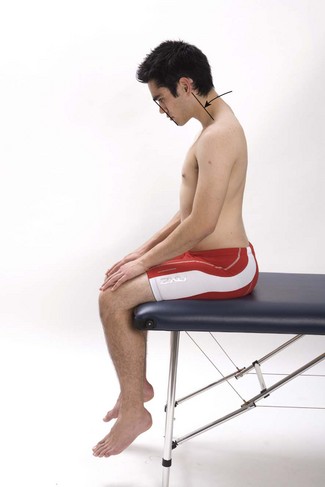

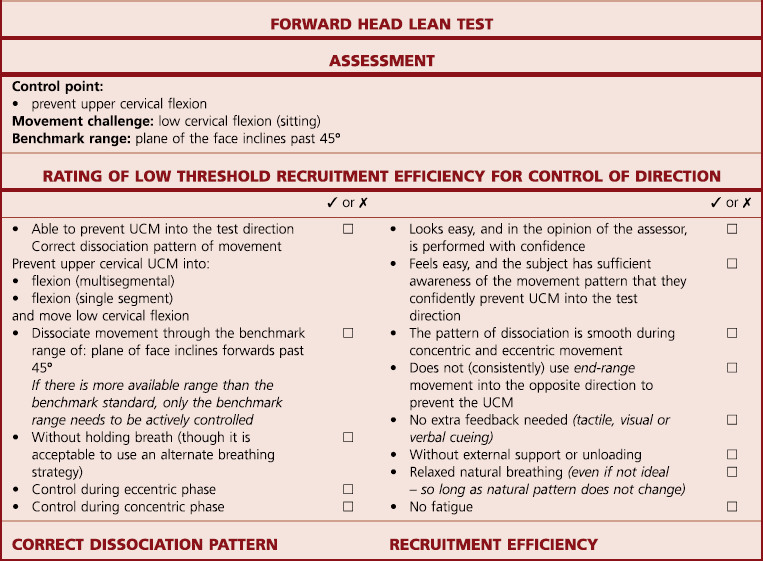

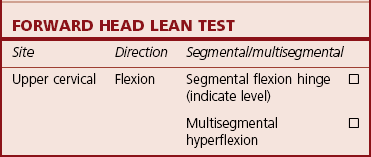

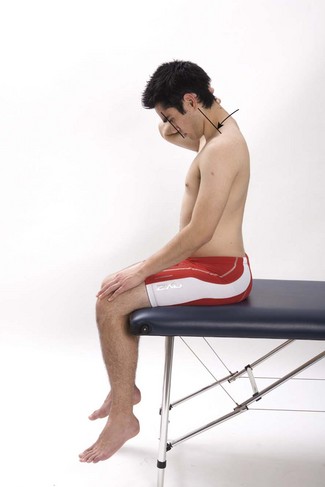

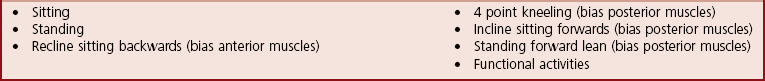

T32 Forward head lean test (tests for upper cervical flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Upper cervical flexion UCM

Rating and diagnosis of cervical flexion UCM

Correction

FEEDBACK TOOL

PROCESS

Self-palpation

Palpation monitoring of joint position

Visual observation

Observe in a mirror or directly watch the movement

Cueing and verbal correction

Listen to feedback from another observer

T33 Arm extension test (tests for upper cervical flexion UCM)

Test procedure

Upper cervical flexion UCM

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The cervical spine