1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Associated or not with latissimus dorsi injuries, teres major injuries occur only rarely. Few cases have been described in the literature and they have generally involved water skiers and baseball pitchers.

We are reporting here on a tendon tear of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi in a professional boxer. This is the first reported description of an injury to the two muscles in a boxer. Up until now, most of the publications dealing with trauma in boxers have studied maxillofacial trauma and the consequences of repeated blows to the head . Conversely, teres major injuries have not been the subject of specific works.

1.2

Case report

The patient was a 28-year-old, right-handed professional boxer, who complained of left dorsal and laterothoracic pain originating in training; it occurred as an uppercut he had readied was being eluded. Initial treatment consisted in rest from sport, use of ice packs and administration of analgesics. Four days later, he consulted a physician in a sports trauma medicine department.

The patient presented no medical history and was not receiving any treatment. Physical examination revealed painful limitations in the active range of motion of the left shoulder (abduction was limited to 100° and flexion to 100°, as well) but without passive muscle limitation. Neurological and vascular examination of the upper limb was normal, and there existed no sign of glenohumeral instability.

Muscle testing underscored pain during isometric contraction against resistance of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi, and the pain was amplified when the muscles were stretched out (VAS = 6/10). Teres major examination was carried out in a 3/4 lateral decubitus position; the upper limb was placed in medial rotation and an adduction movement countered by a support at arm level was requested. In latissimus dorsi examination, the patient was positioned in dorsal decubitus and in order to be tested the upper limb was positioned in medial rotation. An adduction and retropulsion movement countered by a support provided by the examiner at the level of the arm and the wrist was likewise requested.

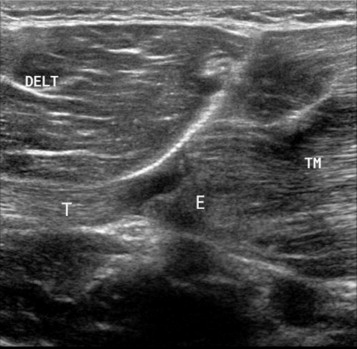

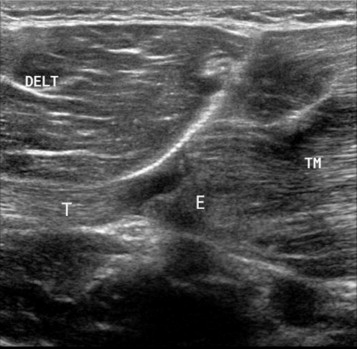

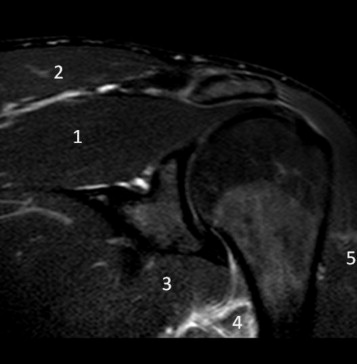

Standard x-rays were normal. Ultrasound ( Figs. 1 and 2 ) and subsequent IRM ( Fig. 3 ) revealed teres major tendon tear extending to the latissimus dorsi.

Improvement was rapid, as functional treatment associated with brief analgesic immobilization was followed by rehabilitation, of which the protocol included analgesic physiotherapy and assisted range of motion recovery that was initially passive, and then active. After that, general muscle reinforcement of the upper left limb along with specific eccentric reinforcement of the injured muscles was carried out. In parallel, reathletization was achieved step by step, taking pain thresholds into account, through less than maximal and minimally painful effort striking an object or exercising with a sparring partner.

Four weeks after the injury, clinical examination was altogether normal and the patient was able and allowed to participate in the scheduled bout which he won by points, without having undergone pain.

At three months, clinical evaluation was completed by concentric isokinetic assessment of the lateral and medial shoulder rotators. Muscle strength testing included a series of 10 warm-up exercises followed by 3 repetitive movements at 60°/s (low speed) and then 10 repetition movements at 180° (high speed). This exercise showed a 25% muscle strength deficit of the left medial rotators at high speed alone (mean max internal rotator/external rotator couple at 72%). The reason we performed this isokinetic test concentrically is that had it been eccentric, it might have been harmful to the patient who still presented with muscular edema in the follow-up MRI.

1.3

Discussion

The teres major originates in the lower angle and the lateral edge of the scapula. Its distal insertion is located at the intertubercular groove of the humerus. It is active in a static phase and also during dynamic effort in medial rotation, adduction and extension of the arm.

Proximal insertion of the latissimus dorsi is located at the level of the dorsal spines of the last six thoracic vertebrae, the thoracolumbar fascia, the posterior part of the iliac crest, the last three ribs and the inferior angle of the scapula. The distal tendon is wrapped around the teres major and inserted along the intertubercular groove of the humerus. The latissimus dorsi is a shoulder extensor that also allows adduction and internal rotation of the humerus. It sets the scapula against the rib cage during anterior elevation of the arm. Moreover, through synergy with the great pectoral and the teres major muscles, the latissimus dorsi enables the trunk of the body to be projected upwards or forwards when the arms are posed above the head, as is the case during a climb.

The two muscles have the same function and their respective tendons run on similar paths. In addition, electromyographic studies have come to the conclusion that the two muscles are activated as joined components of a single muscle structure . Activity of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi is much greater in a professional athlete than in an amateur player, which means that the former is predisposed to more frequent injury than the latter .

Myotendinous tears of the teres major tendon have only rarely been described in the literature. Few cases have been indexed, and they involve ruptures of the teres major tendon that are either isolated or associated with latissimus dorsi tears. The conjoined nature of these injuries is explained by the anatomical proximity of the two tendons and by their functioning as a “muscle unit” . The injuries occur in young male athletes, and among the sports incriminated are baseball and water ski . In the majority of cases the teres major tear arises from macro-trauma after brusque eccentric contraction . One case involves progressive onset of a chronic lesion in an amateur golfer .

The role of the latissimus dorsi in athletic gestures has been analyzed and documented, particularly in electromyographic studies . It is most intensively active during the acceleration phase initiated by an “arming” gesture and culminating in contact of a racket with a tennis ball, or through release of a baseball by a pitcher.

Up until now, no electromyographic study has been devoted to the action of the teres major during an athlete’s gestures, and yet it would appear that its action can be considered as similar to that of the latissimus dorsi, given the anatomical relationship and the identical function of the two muscles .

Two types of injury-producing mechanisms have been described.

The first one corresponds to the sudden application of a traction force on an extended arm. Already outstretched and possibly overextended, the teres major and the latissimus dorsi counteract the movement with an eccentric contraction. The mechanism has been described in water skiers during the tensioning of the tow rope of a boat leaving shore. Comparable trauma has been reported in a SWAT (law enforcement unit) team member who found himself abruptly suspended to an overhead bar he had jumped to grasp .

The second mechanism consists in a violent, “full-speed” contraction occurring when the muscles involved are maximally outstretched, as is the case in the previously mentioned overhead throwing of a baseball or in a tennis server’s likewise overhead motion as he strikes the ball with full force .

However, the injury-producing mechanism in our patient does not correspond to any of those previously described. After all, he hurt himself as the uppercut he had readied was being eluded by a sparring partner, and in his preparation he carried out adduction, flexion and lateral rotation of the shoulder from the bottom to the top, and not vice versa; anterior arm elevation was swift and strong. As the “ascending” gesture draw to a close, the teres major and the latissimus dorsi were eccentrically solicited, and the solicitation was accentuated by the sidestepping of the sparring partner who compelled our patient to exaggerate his gesture as he attempted to touch his “phantom” opponent.

As regards the teres major tendon tears that have been described up until now, 57% are humeral insertion avulsions , 21.5 involve myotendinous lesions and 21.5% are muscle lesions . The lesions closest to the muscles appear to have a better prognosis than either the bony avulsions or the injuries of the myotendinous junction . Other factors contributing to a poor prognosis are the size of the lesion (> 50% of the fibers), and the presence of an intramuscular hematoma.

The different authors are in agreement on the clinical presentation of the lesions. The initial clinical picture shows brusque, highly intense pain with a sensation of posterior axillary tear. Functional impotence is pronouncedly present. On examination, an edema or a hematoma may be found in the axillary area. There may also be a palpable mass at the lower level of the scapula corresponding to the retracted muscles. Active range of motion may be diminished, even though passive examination reveals nothing abnormal. Muscle testing of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi is likely to give a more precise diagnosis, while the rest of the examination is normal.

The diagnosis is subsequently confirmed by imagery. After having standard x-rays eliminate avulsion tear as an explanation, ultrasound and MRI assume a key role, particularly in the exclusion of differential diagnoses. However, the injured muscles are located on the periphery of the window produced by conventional shoulder MRI. As a result, a teres tendon major rupture at the humeral insertion with muscular retraction is not necessarily on MRI carried out with standard protocol for the shoulder , and MRI of the upper thorax is consequently to be preferred .

As regards therapeutic support, the low prevalence of these tears explains the lack of written recommendations. Surgical management and functional treatment have nonetheless been described.

The authors advocating surgical treatment emphasize the period of recovery time an athlete will accept, the need for complete restoration of muscle strength and the goal of resuming competition at the previously achieved level. In fact, there seem to exist specific indications in case of combined injuries (great pectoral, rotator cuff) or distal bony avulsion.

As of now, only two cases of surgical treatment have been reported in the literature. A SWAT team member underwent tendon repair 4 weeks after conjoined rupture of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi tendons . The type of injury was not described precisely. After the operation, short-term immobilization followed by muscle exercise on a pendulum apparatus and subsequent, more intensive rehabilitation (from the 6th week) facilitated recovery, so that athletic and professional activities were resumed in the 17th week, with no deficit in muscle strength. Garrigues et al. report on the case of a water skier having suffered from isolated avulsion of the teres major at the humeral insertion. Surgery consisted in suture anchor reinsertion followed by six weeks of immobilization and progressive muscle reinforcement. At 1 year, there persisted a strength deficit of 27% in medial rotation and 24% in extension on the operated side.

The other described cases all involved functional treatment in which short-term analgesic immobilization was followed by rehabilitation and progressive reathletization in accordance with a variety of protocols. The results were satisfactory; there were no functional sequels in the area of the injured shoulder. All of the patients, except for a baseball pitcher , were able to resume high-level sports activity at the levels of competence and competition that had been theirs previous to injury. Their return to form covered time lapses ranging from 1 month to 10 months . Length of recovery period depended largely on type of injury; it was of greater duration for bony avulsion or in case of combined teres major and latissimus dorsi injury than for myotendinous tear or for simple muscle injury.

As regards our patient, rehabilitation and reathletization were started early (one week) and it was subsequently possible for him to resume competition, without symptoms, within 2 months. One of the explanations for his rapid return to form could be the fact that the functional importance of the injured muscles is less in boxing than in throwing; that much said, no electromyographic study has been carried out. It should be added that during evaluation 3 months after the injury had occurred, the subject still presented a 25% isokinetic strength deficit at high speed for the medial rotators of the injured shoulder.

To sum up, post-surgical recovery time is greater than the time taken for functional, non-surgical treatment, and the results are equivalent, at both the functional level (return to previous athletic form, recuperation periods compatible with high-level practice) and as regards the time needed to recover muscle strength (possible persistence of a small-scale strength deficit, particularly in medial rotation). While in daily life muscle compensations limit the functional consequences of the loss of strength, the latter may be bothersome for high-level athletes in the practice of their sports.

1.4

Conclusion

We have reported on the first case of a professional boxer having presented with a myotendinous tear of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi following avoidance by a sparring partner of the uppercut he had readied (eccentric intrinsic trauma). Clinical examination led to rapid diagnosis that required confirmation by imagery (ultrasound and MRI with adjusted window). The data in today’s literature tend to favor functional treatment (short-term analgesic immobilization followed by a program of targeted rehabilitation and progressive reathletization) enabling the athlete to resume sports activities at the same level. The time frame for recovery may vary.

Disclosure of interest

The authors have not supplied their declaration of conflict of interest.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Les lésions du muscle grand rond, associées ou non à des lésions du muscle grand dorsal, sont rares. Très peu de cas sont décrits dans la littérature et concernent surtout des skieurs nautiques et des pitchers (lanceurs au baseball).

Nous rapportons la survenue d’une désinsertion myotendineuse du grand rond et grand dorsal chez un boxeur professionnel. Il s’agit de la première description de lésion de ces deux muscles chez le boxeur.

À ce jour, la plupart des publications traitant de traumatologie chez le boxeur portent sur les traumatismes maxillo-faciaux et sur les conséquences des traumatismes crâniens répétés . En revanche, les lésions musculotendineuses n’ont pas fait l’objet de travaux particuliers.

2.2

Cas clinique

Il s’agit d’un boxeur professionnel de 28 ans, droitier, consultant pour douleurs latéro-thoraciques et dorsales gauches survenues à l’entraînement, lors d’un mouvement d’uppercut esquivé. La prise en charge initiale a consisté en un repos sportif, un glaçage et la prise d’antalgiques. Il a ensuite consulté dans le service de médecine et traumatologie du sport quatre jours plus tard.

Ce patient ne présente aucun antécédent et ne prend aucun traitement. L’examen physique retrouve une limitation douloureuse de l’ensemble des amplitudes articulaires actives de l’épaule gauche (l’abduction était limitée à 100° et l’élévation antérieure à 100°) sans limitation en passif. L’examen neurologique et vasculaire du membre supérieur est normal. Il n’y a pas de signe d’instabilité gléno-humérale.

Le testing musculaire met en évidence des douleurs lors de la contraction isométrique contre résistance des muscles grand rond et grand dorsal, majorées en course externe (EVA = 6/10). Le testing du muscle grand rond se réalise en décubitus de ¾ latéral, le membre supérieur est placé en rotation médiale et doit alors réaliser un mouvement d’adduction contrarié par un appui au niveau du bras. Pour tester le muscle grand dorsal, le patient est en décubitus dorsal, le membre supérieur à tester est placé en rotation médiale et doit réaliser une adduction et rétropulsion contrariée par un appui de l’examinateur au niveau du bras et du poignet.

Les radiographies standard sont normales. Une échographie ( Fig. 1 et 2 ) puis une IRM ( Fig. 3 ) ont permis de mettre en évidence une désinsertion myotendineuse distale du muscle grand rond qui s’étend au muscle grand dorsal.