Techniques for Intradural Tumor Resection

Christine L. Hammer

Sanjay Yadla

James S. Harrop

Primary spinal cord tumors (SCTs) or neoplasms represent approximately 2% to 4.5% of all central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms (4,10). They are significantly less common, 10 to 15 times fewer, than primary intracranial tumors (10). These SCTs are classified or categorized based on their anatomical location such as extradural, intradural extramedullary, or intradural intramedullary (10,42). Other clinical features and factors that are significant in their diagnosis include clinical presentation, age, genetic disorders, and gender of the patient (2).

The focus of this chapter is the diagnosis and management of primary intradural SCTs. In general, intradural intramedullary tumors are more common in children, and intradural extramedullary tumors are more common in adults (42). In adults, these are compressive rather than invasive and primarily treated surgically. Postoperative outcome depends on preoperative neurologic status, histology, grade, and location of the tumor (10). Patients typically present with a pain syndrome with either localized back pain or radicular pain, and then symptoms will eventually progress to myelopathy if not treated (2). The clinical presentation and imaging studies are important in the diagnosis since there is a large differential diagnosis of other abnormalities that may present with similar features (2).

INTRADURAL EXTRAMEDULLARY

Intradural extramedullary tumors represent about 80% of adult SCTs and approximately 65% of SCTs in children (2,22). They can be further classified by histology or cell-type origin. Examples include meningiomas that arise from arachnoid cap cells of the leptomeninges or benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) such as schwannomas and neurofibromas that arise from the cells covering the nerve roots (42). Other less common tumors include paragangliomas, hamartomas, metastases,

peripheral nerve sheath myxomas, lipomas, sarcomas, and vascular tumors (10,42). About 50% of intradural extramedullary tumors and 77% of PNSTs have extradural extension (32). Meningiomas, hamartomas, and sarcomas are other intradural extramedullary tumors that are not limited by the dura. About 10% to 15% of meningiomas occupy both intra- and extradural space (22,42).

peripheral nerve sheath myxomas, lipomas, sarcomas, and vascular tumors (10,42). About 50% of intradural extramedullary tumors and 77% of PNSTs have extradural extension (32). Meningiomas, hamartomas, and sarcomas are other intradural extramedullary tumors that are not limited by the dura. About 10% to 15% of meningiomas occupy both intra- and extradural space (22,42).

Spinal meningiomas are characteristically benign (WHO grade 1) tumors located in the thoracic spine of middle-aged women (2,46,49). Most lesions are solitary and located lateral to the spinal cord. Clinically, these lesions present with local or radicular pain and motor dysfunction greater than long tract or radicular sensory disturbances or sphincter deficits (10,22,43).

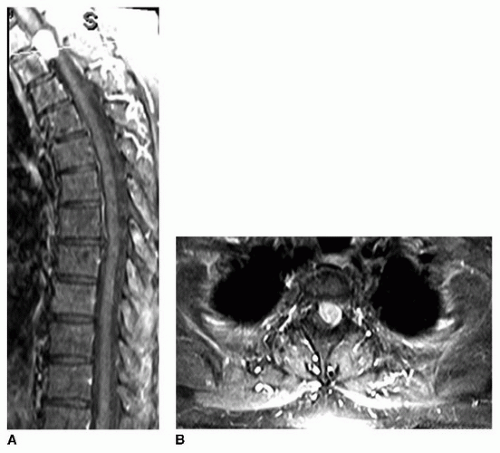

About 25% of intradural extramedullary tumors are PNSTs (42). However, these tumors are rarely simply intradural or extramedullary in location. About 10% to 15% are dumbbell shaped with extension beyond the dura into the vertebral foramen (28). These tumors are usually located at the anterior lateral aspect of the cord. While most intradural PNSTs are benign, about 2.5% are malignant with about half of those cases occurring in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) (10,42) (Fig. 31-1).

Neurofibromas may be classified as solitary, multiple, or plexiform with a network of neurofibroma tissue bundles extending over nerve roots often involving multiple branches and plexi (10). These tumors contain Schwann cells, collagen, and reticulin fibers and encase rather than displace nerve roots (2). While most neurofibromas are benign (WHO grade 1), malignant forms usually arise from solitary or plexiform neurofibromas, and irradiation has been implicated in malignant transformation of neurofibromas (2,16,17,25). Approximately 90% of spinal cord neurofibromas are solitary tumors; however, multiple neurofibromas, as well as multiple schwannomas and meningiomas, may be found in patients with neurofibromatosis type two (NF-2) (2,4,17,47). Clinically, neurofibromas present often with pain and sensory dysesthesias (10).

Schwannomas, the most common spinal nerve tumor, usually arise from the dorsal (sensory) nerve root compared with neurofibromas, which usually arise from the ventral (motor) root (10,42). These tumors are typically benign (WHO grade 1), solitary, slowly growing PNSTs (2). When associated with NF-2, there may be multiple tumors, and they may precede the development of vestibular tumor and may also have a higher risk of malignant transformation (2,19). These are usually found incidentally secondary to their frequent involvement of nonfunctional nerve roots with one study showing just 23% with postoperative motor or sensory deficits (31). When symptomatic, a schwannoma may present with shooting pain or paresthesias associated with contact and rarely present with pain (10). These tumors grow along the nerve unlike neurofibromas which tend to infiltrate the neural elements. Surgically, this is important since schwannomas typically can be dissected off the nerve, thus preserving function, as opposed to the neurofibromas, in whose case complete resection often results in loss of function.

INTRADURAL INTRAMEDULLARY

Intradural intramedullary spinal tumors are the rarest spinal tumors and account for just 5% to 10% of CNS tumors, 20% of all SCTs in adults, and about 30% of all SCTs in children (2,22,42). Intramedullary spinal tumors may be of glial origin, such as ependymomas and astrocytomas, or of nonglial origin, such as hemangioblastomas, cavernomas, metastases, or lymphomas (2). In adults, approximately 60% to 70% are ependymomas and 30% to 40% are astrocytomas (10,24).

Patients typically present with back pain localized to the spine (24). Patients with glial SCTs typically have pain that is worse at night or upon awakening. This is believed to be secondary to tumorinduced disturbances in venous outflow in the valveless spinal canal venous system, referred to as the Batson plexus, causing venous engorgement in the supine position (24). Intramedullary tumors may present with “central cord syndrome” features of disassociation between pain/temperature sensation and proprioception as well as symmetric motor neuron dysfunction and myelopathy (10,47).

Spinal ependymomas can present throughout a patient’s life but are more common in middleaged adults. This is compared to spinal astrocytomas, which are more commonly found in children (10,47). These spinal tumors account for about 35% of all CNS tumors in adults and about 60% of all intramedullary tumors (2). Unlike meningiomas, which are more common in women, these tumors exhibit a gender preference for men (39,42).

Approximately 65% of patients with ependymomas have intraspinal syrinxes (47). Forty percent of intradural ependymomas are of the subclassification of myxopapillary. These tumors are believed to arise from the filum terminale and occur at the conus medullaris or in the filum terminale (10,42). Ependymomas usually present with sensory disturbances, particularly dysesthesias initially, and progress to pain in a distribution related to tumor location.

Spinal cord astrocytomas are the second most common spinal tumor type in adults with a prevalence in the first three decades of life and account for 80% of intramedullary tumors in children (42,47). Most pediatric cases are benign, while malignant astrocytomas and glioblastomas account for about 10% of intramedullary spinal cord astrocytomas in children (43). In adults, the malignant fibrillary astrocytomas are more common but may have pilocytic features (42,44). Low-grade, WHO grade 1 to 2, fibrillary astrocytomas typically have excellent surgical outcomes. However, higher-grade spinal tumors are associated with a poor outcome secondary to high incidence of dissemination via spinal fluid and rapidly progressive course (11,45). Radiographically, these tumors’ radiographic features usually illustrate a fusiform expansion of the spinal cord. As with most spinal intramedullary cord tumors, weakness usually follows pain and sensory symptoms (22). Sensory symptoms tend to be paresthesias rather than dysesthetic pain (burning pain) as with ependymomas (24). Prior to diagnosis, symptom onset may occur over years in cases of low-grade astrocytomas or over months for high-grade gliomas (24).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree