Tarsometatarsal Lisfranc Injuries: Evaluation and Management

Bruce J. Sangeorzan

Kyle F. Chun

Stephen K. Benirschke

Benjamin W. Stevens

INTRODUCTION

Injuries to the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint complex, also known as the Lisfranc joint, are relatively uncommon injuries, constituting approximately 0.2% of all fractures in the United States annually. Disruptions of any of the TMT articulations are loosely defined as a Lisfranc injury, but the eponym is more specifically defined as the articulation between the medial cuneiform and the base of the second metatarsal. This articulation is considered the “keystone” to the midfoot, stabilizing both the longitudinal and transverse arches of the midfoot. Injuries can be purely ligamentous, osseous, or both. Lisfranc-equivalent injuries can present in the form of contiguous proximal metatarsal fractures, tarsal fractures, and combinations of both, the unifying factor remaining disruption of the TMT joint complex and anatomic configuration of the midfoot. Many injuries are subtle, and a high index of suspicion is required for timely diagnosis and treatment.

The mechanism of injury can be both high and low energy and usually occurs in a position of a plantarflexed foot. A hyperflexion/compression/abduction moment is exerted on the forefoot and subsequently transmitted to the TMT articulation. This results in a combination of the aforementioned soft-tissue and osseous injuries and usually displaces the metatarsals in a dorsal-lateral direction. Variations to this pattern exist and vary depending on the mechanism and energy of the injury (classification). Most injuries require surgical intervention and are challenging to treat.

Recovery from TMT joint injuries is often prolonged and associated with varying amounts of long-term disability. Missed injuries can result in progressive foot deformity and can lead to chronic pain, dysfunction, lost time from work, and failure to regain preinjury activity levels.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The primary surgical indication for treatment of a tarsometatarsal injury is the knowledge that the injury will do poorly with nonoperative treatment. Conceptually, tarsometatarsal injuries that lead to a loss of the arch or significant foot deformity if treated conservatively should be treated surgically. These include both displaced injuries and subtle injuries that have instability in two planes. The decision to treat a tarsometatarsal injury surgically is based on both physical examination and radiographic studies.

The transverse and longitudinal arches of the foot depend on the tarsometatarsal joints to make the foot sufficiently rigid to support the body, much as the apical blocks of ice support an igloo. Unstable tarsometatarsal injuries that compromise this structural integrity may result in deformity of the foot. In the majority of displaced injuries, the metatarsals displace dorsally and laterally on the tarsal bones, which produces pes planus with forefoot abduction. As a result, when weight is borne on the foot, it collapses. During heel lift, further

deforming forces that act on the midfoot tend to exacerbate the deformity. For the metatarsals to displace in this direction, the plantar tarsometatarsal (Lisfranc) ligaments must be disrupted. Operative treatment is indicated when an ambulatory patient has an injury that renders the foot mechanically unsound, deformed, or both.

deforming forces that act on the midfoot tend to exacerbate the deformity. For the metatarsals to displace in this direction, the plantar tarsometatarsal (Lisfranc) ligaments must be disrupted. Operative treatment is indicated when an ambulatory patient has an injury that renders the foot mechanically unsound, deformed, or both.

Ambulatory patients with a displaced and unstable tarsometatarsal joint injury that is apparent on plain radiographs are candidates for surgery. However, when the injuries are subtle or apparently nondisplaced, operative treatment is indicated only when two-plane instability is detected on clinical examination or stress x-rays. Because the foot functions in weight bearing, the integrity of the plantar ligaments is of greater importance than that of the dorsal ligaments.

Contraindications to surgical intervention include nonambulatory individuals, patients with serious vascular disease unlikely to heal a surgical incision but who have no significant deformity, severe peripheral neuropathy, or an injury that is unstable in only the transverse plane. Lisfranc injuries with only bone injuries at the base of the metatarsals can often be treated by casting or by closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. When deformity and compromised circulation are found, the surgeon faces a dilemma. Leaving a deformity puts the patient at risk for ulceration, while treating it surgically puts the patient at risk for wound-healing problems. In this circumstance, vascular studies may be indicated to determine whether a revascularization procedure would be beneficial prior to orthopedic intervention.

Neurologic impairment is also a cause for concern. The physician must decide whether sufficient energy produced the injury or whether an underlying neuropathic condition exists. Trivial injuries that cause significant displacement should stimulate an investigation into a possible neuropathic condition. A Charcot neuropathic foot is a distinct clinical entity and requires different management techniques. The treatment of a Lisfranc injury in the presence of peripheral neuropathy requires more fixation and a longer period of postoperative protection.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History and Physical Examination

Lisfranc injuries are often missed, and it is one of the few injuries in orthopedics where the maxim “the eye doesn’t see what the mind doesn’t search for” is most appropriate. Most injuries occur following high energy trauma such as motor vehicle or motor cycle accidents or falls from heights. Many of these patients have multisystem trauma and are managed with Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols. However, a small but substantial number of injuries occur following a lower energy mechanism that occurs in sports such as football, soccer, equestrian activities, etc. The physical examination should document the status of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses, the integrity of the skin, and the habitus of the foot. Tendon entrapment may be demonstrated by an altered, uncorrectable position of the toes or midfoot. Intact or altered sensation should be documented.

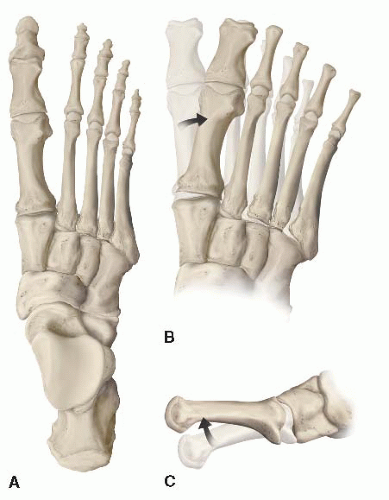

Instability can often be determined on physical examination. The physician grasps the metatarsal heads and applies a dorsal force to the forefoot while the other hand palpates the tarsometatarsal joint. Dorsal subluxation or dislocation of the bases of the metatarsals strongly suggests instability (Fig. 36.1). If the first and second metatarsals can be displaced medially or laterally as well, global instability is present, and surgical treatment is required. Lower energy injuries often interrupt the dorsal ligaments or medial capsule but do not disrupt the strong structurally important plantar ligaments. When the plantar ligaments are intact, dorsal subluxation does not occur with the stress examination. These injuries may be treated nonoperatively in a cast.

Imaging Studies

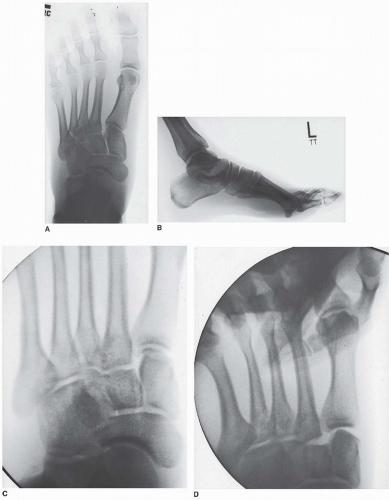

In a patient with pain and swelling in the foot an AP, oblique, and lateral radiograph should be obtained. Oblique views are essential in evaluating midfoot injuries and should always be included. With ligamentous disruption of the midfoot without fracture, non-weight-bearing radiographs may be deceptively benign. The ligaments are torn with the initial injury displacement; however, when the deforming force is removed, the foot may “spring back” into a reduced position, concealing gross instability.

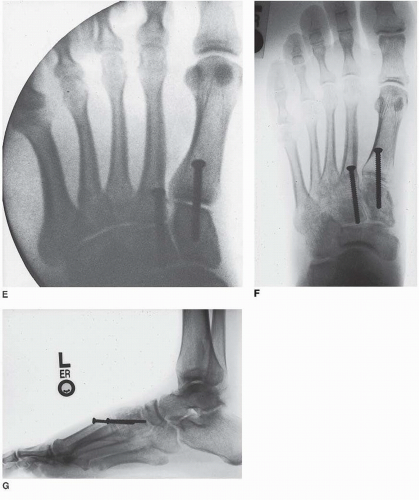

Therefore, the physician should be suspicious whenever midfoot swelling and pain are present. In stable patients, if a subtle midfoot injury is suspected, additional imaging should include a simulated weight-bearing AP, lateral, and oblique view of the foot. If disruption of the tarsometatarsal joint is found on several radiographic projections, a tarsometatarsal injury is likely. There are five critical radiographic signs that indicate or imply midfoot instability. The first and most reliable radiographic sign is disruption in the continuity of a line drawn from the medial base of the second metatarsal to the medial side of intermediate cuneiform on the anteroposterior (AP) and oblique views (Fig. 36.2A). The second most reliable radiographic sign is widening of the interval between the first and second ray. And the third important radiographic observation is the medial side of the base of the fourth metatarsal should line up with the medial side of the cuboid on the oblique view. This is a “soft sign” because the cross section of the metatarsal base is not equal to the cross section of the cuboid. As a result, a step-off may be present if the angle of the beam is slightly misdirected. Fourth, on the lateral view, the metatarsals should align with the cuneiforms at the dorsal cortex. When a ligament injury is present, the metatarsals are usually dorsally displaced in relation to the cuneiforms. Finally, any disruption of the medial column line (MCL), a line tangential to the medial aspect of the navicular and medial cuneiform, is highly suggestive of a midfoot injury. The disruption will show on the intersection of the base of the first metatarsal on an AP view taken during weight bearing.

If the presence, location, or degree of injury in a patient with a midfoot injury is uncertain, stress x-rays with or without sedation or anesthesia should be taken in two planes. Typically, these are done using fluoroscopy to make certain that the correct plane is achieved during imaging. When the index of suspicion is high, the stress roentgenogram is performed in an operating room (OR), so that if the injury is confirmed, surgery can be done under the same anesthetic. If x-rays are done in AP, lateral, and oblique planes, and stress views are obtained when there is uncertainty, additional imaging modalities should not be necessary. Computed tomographic (CT) scans of the midfoot are difficult to interpret. The role of the magnetic resonance imaging scan has not been established.

TIMING OF SURGERY

Several factors must be considered when determining the timing of surgical intervention. These include the amount of soft-tissue swelling, the availability of imaging studies, and the degree of displacement. Surgery should be done emergently only in the presence of a compartment syndrome, open injury, an irreducible fracture dislocations, or a deformity that threatens the integrity of the skin. Most open injuries should be irrigated, débrided, and stabilized early.

Given the complexity of many tarsometatarsal injuries and their relative rarity, definitive management is best delayed until experienced personnel are available. Aside from the circumstances discussed above, most Lisfranc injuries can be scheduled electively for daytime surgery with a rested and experienced surgical team. The extremity can be elevated until the swelling has resolved, and the fracture addressed on a more “elective” basis. In some high-energy cases associated with significant soft-tissue injury and swelling, definitive management is often delayed 2 or 3 weeks. In patients with grossly unstable injury patterns and significant soft-tissue compromise, the foot should be temporarily stabilized with a splint or external fixator and definitive fixation delayed until the soft-tissue envelope has improved.

SURGICAL TACTIC

Surgery requires a C-arm fluoroscopy unit and an appropriate radiolucent OR table, and positioning equipment that facilitates patient positioning (i.e., positioning rolls, extremity ramp). Standard small fragment and minifragment instrument trays that contain point-to-point reduction clamps, a dental pick small Homan retractors, Freer and AO elevators, and Kirschner wire (K-wires) will suffice. A small battery powered drill is also necessary.

The implants needed to surgically treat TMT injuries include screws ranging in size from 2.0 to 3.5 mm. A stronger 4.0-mm cortical screw is also used frequently at our institution. If external fixation is anticipated, the appropriate external fixation pins, clamps, and bars should be available. Specialized modular foot implants and plates may be helpful in difficult or complex fracture patterns.

SURGERY

Stress X-Rays

In some patients with foot trauma and clinical and radiographics signs suggestive of midfoot instability, stress fluroscopic radiographs are indicated. In some patients, this can be done in the radiology department, while other patients who probably require surgery are done in the OR. After appropriate IV sedation or a general anesthetic is administered, the OR table is bent at the knees so the foot is relatively parallel to the floor. While wearing lead gloves, the surgeon grasps the first and second metatarsal heads with one hand and the hind foot with the other. With the thumb placed over the cuboid to act as a fulcrum, the forefoot is abducted, and an AP fluroscopic image is obtained. Instability is present if a gap occurs on the medial side of the first or second tarsometatarsal joint, or disruption of the MCL is produced (Fig. 36.2D). Stress views in the lateral plane are performed if any uncertainty exists. With the knee extended, the surgeon grasps the midfoot with one hand and the forefoot with the other and acutely plantarflexes the foot through the tarsometatarsal joint. A cross table lateral image is obtained. Although the tarsometatarsal joints may angulate, they should not open asymmetrically. Subluxation indicates that the joints are unstable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree