Talar Avascular Necrosis

Christopher F. Hyer

William T. DeCarbo

Avascular necrosis (AVN) or osteonecrosis is defined as a disease resulting from temporary or permanent loss of the blood supply to bone (1). Bone without blood supply and nourishment will necrose, causing the bone to collapse (1). This process is often very painful and debilitating, particularly in the case of the talus since it supports both the ankle and subtalar joints (STJs) (Fig. 115.1A).

There are many causes of AVN to bone, including include idiopathic, alcoholism, corticosteroid use, caisson disease (decompression sickness), vascular compression, hypertension, vasculitis, thrombosis, bisphosphonates, sickle cell anemia, and rheumatoid arthritis. The most common cause in the foot and ankle is posttraumatic talar fracture (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 and 11) (Fig. 115.1B).

ANATOMY

The unique anatomy and tenuous blood supply of the talus makes it susceptible to AVN. The talus comprises a body, head, and neck. The talus articulates with the tibia, the malleoli, the navicular, and the calcaneus. Due to the multiple articulations, the talus is covered with approximately 60% of hyaline cartilage (12). This high percentage of hyaline cartilage coverage leads to a precarious blood supply since there are limited nonarticular surfaces for the vessels to penetrate.

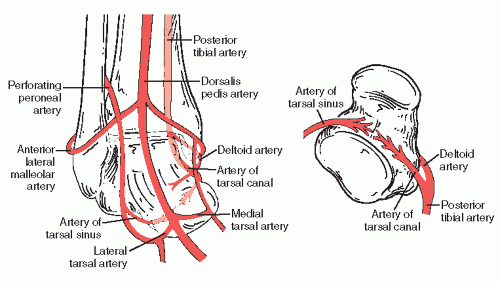

The arterial supply of the talus is made up of both extraosseous and intraosseous circulation. The three main branches that supply the talus are the posterior tibial artery, the dorsalis pedis artery, and the perforating peroneal artery. The posterior tibial artery gives off the artery of the tarsal canal. This branch enters the canalis tarsi and anastomoses with the artery of the sinus tarsi. This anastomosis helps to supply the talar head and neck. The artery of the tarsal canal gives off a branch deep to the deltoid ligament called the deltoid artery. This artery supplies the talar body. Laterally, the artery of the sinus tarsi is formed by the anastomosis of the perforating peroneal artery and the lateral tarsal artery. The lateral tarsal artery is a branch of the dorsalis pedis artery (13,14,15,16,17 and 18). The intraosseous blood supply of the talus is made up of various vascular foramina. The talar head is supplied primarily by the anterior tibial artery. The deltoid artery contributes significantly to the intraosseous circulation in the medial and proximal portions of the talar body. The anterolateral talar body and the posterior tubercles are relatively avascular (12) (Fig. 115.2).

ETIOLOGY

The true pathomechanism of AVN remains unknown. The three broad causes are idiopathic, medication induced, and traumatically induced. It appears that an acute injury comprising vascular disruption, along with a delayed form of microvessel thrombosis and fibrosis in acute traumatic events, leads to AVN (19).

Glucocorticoid administration is the most common cause of nontraumatic AVN (20,21) (Fig. 115.3). There are many theories to describe this etiology. One theory suggests that fat embolism from the liver, the marrow fat cell, or from destabilization and coalescence of plasma lipoproteins could be responsible. Another theory states that the associated insulin resistance favors the development of hypertension and arteriosclerosis. Suggestions have also been made that steroidinduced osteoporosis can cause microfractures in susceptible bone (22). Another factor that seems to contribute to the development of AVN is the inhibition of angiogenesis. This inhibition is apparently caused by reduction in proteolytic activity by the synthesis of plasminogen activator inhibitor (20,23).

Another potential cause of AVN is alcoholism. It has been reported that patients who consume up to 320 g of ethanol per week had a 2.8 increase in the relative odds of developing AVN (24). As mentioned above, several other case reports have been made in regards to the development of AVN; however, the majority of causes for the talus remains trauma.

CLASSIFICATION

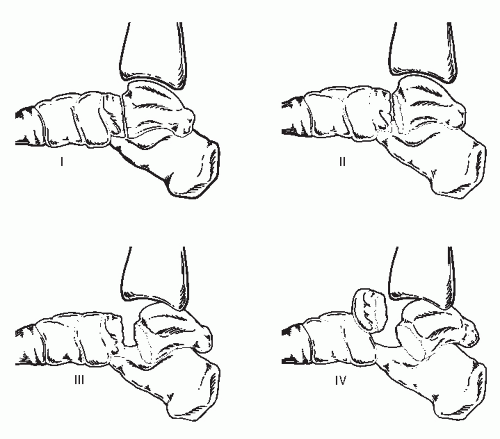

In regards to the talus, it is generally accepted that the incidence of AVN is dependent on the severity of the fracture and the degree of displacement (25,26). There are many classifications for talar fractures, depending on the anatomic location of the fracture (27,28,29,30,31,32 and 33). The most accepted classification system, that also serves as a prognostic indicator, is that described by Hawkins and later modified by Canale and Kelly (27,28) (Fig. 115.4).

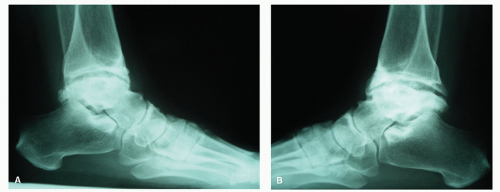

This classification system comprises four types, with percent incidences of developing talar AVN. The incidence of AVN with talar neck fractures is reported as 0% to 100%, depending on severity and the amount of dislocation. More than half of all talar fractures are talar neck fractures, and this accounts for 90% of all traumatic AVN (12,27,28,34,35 and 36) (Fig. 115.5).

Hawkins type I fractures are nondisplaced vertical neck fractures. The reported incidence of AVN is 10%. Hawkins type II fractures consist of a vertical talar neck fracture with either subluxation or displacement of the STJ. The reported incidence of AVN is 42%. Hawkins type III fractures are characterized by a vertical talar neck fracture with subluxation or dislocation of both the ankle and STJs. The AVN incidence in this type is reported at 91%. Hawkins type IV fractures, as

modified by Canale and Kelly, consist of a vertical talar neck fracture with subluxation or dislocation of the ankle, STJ, and the talonavicular joint. Type IV fractures had a reported incidence of AVN at 100% (27,28,37).

modified by Canale and Kelly, consist of a vertical talar neck fracture with subluxation or dislocation of the ankle, STJ, and the talonavicular joint. Type IV fractures had a reported incidence of AVN at 100% (27,28,37).

PRESENTATION

Patients with AVN of the talus usually present with pain and swelling. The degree of symptoms usually is determined by the integrity of the articular surface involvement (1). Patients typically have a history of previous injury or trauma. Initially, patients may complain of stiffness in the ankle and “soreness” with extended weight-bearing activities. Occasionally in the early stages, patients may be asymptomatic and without radiographic changes, suggesting AVN. As the AVN and collapse progress, the articular incongruity increases. Pain and mechanical symptoms such as clicking, locking, and grinding are the typical presenting complaints. Often, pain progresses from a predominately weight-bearing pain to more persistent and constant pain. Sequelae such as anterior ankle impingement and arthritis of the ankle, the STJ, and less commonly, the talonavicular joint, occur. As the process continues, collapse of the talar body can present as shortening of the affected limb.

DIAGNOSIS

Identifying the symptomatic joint or joints is the focus of the physical exam. Diagnostic blocks can be performed to identify the affected joints. A complete history to rule out trauma or other systemic or medical causes is pertinent. Various imaging techniques can be used to assist in the diagnosis of AVN. Plain radiographs and MRI remain the most used and beneficial modalities (12). Plain radiographs may reveal early findings of sclerosis and cystic changes or collapse with advanced stages. The Ficat and Arlet classification has been adapted for the ankle to identify the extent of talar disease (38) (Table 115.1).

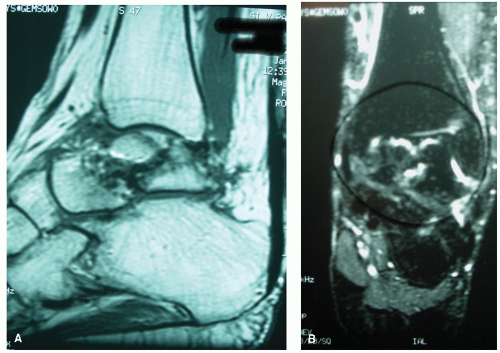

Radiographic evidence of AVN usually occurs within the first 8 weeks after an injury (39). It is important to note that evidence of radiographic abnormalities typically occur in advanced stages of talar AVN when therapeutic intervention may have little to no impact. For this reason, MRI is the most widely used modality to diagnose and potentially prevent further talar damage due to AVN. Due to the bone marrow elements in trabecular bone, which comprises predominantly fat cells, there is a strong signal intensity normally seen in

T1-weighted MR images. In early AVN, diffuse marrow edema produces low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. In advanced stages, the diagnosis of AVN on MRI includes decreased signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images indicative of areas of devascularization or necrotic bone (20,40) (Fig. 115.6). It has been recommended waiting at least 3 months, until bone healing is present, before doing an MRI (12).

T1-weighted MR images. In early AVN, diffuse marrow edema produces low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. In advanced stages, the diagnosis of AVN on MRI includes decreased signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images indicative of areas of devascularization or necrotic bone (20,40) (Fig. 115.6). It has been recommended waiting at least 3 months, until bone healing is present, before doing an MRI (12).

Figure 115.5 Lateral radiograph left ankle: talar neck fracture pattern with high rate of associated AVN. |

TABLE 115.1 Staging of Osteonecrosis of the Talus According to Ficat and Arlet (1950) (38) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

At 6 to 8 weeks after a talar injury, the Hawkins sign is thought to be indicative of talar revascularization. The Hawkins sign is a subchondral radiolucent line along the superior aspect of the talar dome, which classically begins on the medial side of the talar dome (41). This is often visible on the anteroposterior (AP) and mortise view radiographs. Due to fibular overlap, the lateral radiograph is not helpful (27). Hawkins sign indicates an adequate blood supply to the talus reflecting disuse osteopenia and AVN is not present. Complete revascularization of the talus after surgery or injury takes 6 months to 3 years (42). Although the Hawkins sign is highly sensitive, its absence cannot predict avascularity (42).

The concept of partial Hawkins sign has also been described (43). It was previously thought that the Hawkins sign is an all-or-none phenomenon. Cases of partial AVN indicated that partial Hawkins sign is thought to occur due to the fact that most of the blood supply to the talus comes from the medial side (43). When partial AVN occurs, it involves mostly the lateral talus (43,44).

TREATMENT

CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT

The treatment of talar AVN largely depends on whether it is in the early or late stages. In the early stages, it is important to diligently monitor the patient for signs of AVN. The Hawkins sign is most helpful at this initial period. The MRI is also useful, but may be too sensitive in the early stages, as noted above (45). If Hawkins sign is not noted at 6 or more weeks following a talar injury and the talus is radiographically healed, the treatment is then aimed at avoiding late collapse. The most accepted way to protect the talus from further damage due to AVN is with limited or non-weight-bearing (12). Controversy, however, exists as to the degree of off-loading weight and length of protection. Mindell et al (46) treated 13 patients with posttraumatic AVN. Six patients were allowed to bear weight in 6 months following injury, and seven patients began bearing weight 12 months after the injury. Two of the six patients and four of the seven had satisfactory results. Pennal (47) used a patellar tendon brace to avoid collapse of the talus in review of 98 cases until revascularization occurred (Fig. 115.7).

Penny and Davis (48) reported that weight-bearing on a sclerotic, avascular talus poses no danger for dome collapse. Along with Penny and Davis, Hawkins (27) stated that patients lose interest and it is often impractical for a patient to remain nonweight-bearing for the prolonged time it may take for the talus to revascularize. Canale and Kelley (28) treated 23 patients with talar AVN using nonoperative care. They reported those nonweight-bearing for an average of 8 months had fair to excellent results. Those that were partial weight-bearing in a short leg brace or patellar tendon brace had poor to good results and those patients non-weight-bearing for less than 3 months had poor results. Comfort et al (49) advocate weight-bearing status based on the degree of AVN. They stated in partial AVN, total non-weight-bearing is not necessary due to residual nondiseased bone resisting some weight-bearing forces. They recommend a hinged brace to avoid varus and valgus stress of the softer bone. Adelaar (50,51) suggests weight-bearing be dictated by fracture healing. Once the fracture is healed, weight-bearing is determined by the amount of involvement of the talus in AVN. If prolonged protected, limited, or non-weight-bearing has not alleviated the pain, surgical intervention should be considered.

Figure 115.7 Lateral clinical photograph depicting custom-fit patellar tendon weight-bearing prosthesis. |

Hyperbaric oxygenation therapy (HBOT) has been reported as adjunct treatment for delayed Hawkins type III fractures. Mei-Dan et al (52) published a two-case report in which open reduction and internal fixation was performed more than 2 weeks following injury due to a delay in diagnosis. Both patients underwent five treatments a week, 35 sessions, at 2 atmosphere absolute with 100% O2 for 90 minutes. At 3-year follow-up, neither patient had developed talar AVN. The authors suggest the benefit of HBOT helped prevent AVN.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

The surgical treatment for AVN of the talus is dictated by the extent of the disease, both in terms of degree of AVN but also in the extent of anatomic destruction that has occurred. Operative options range from arthroscopic débridement with core decompression, vascularized and nonvascularized autografts and allografts, tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) fusions, tibiocalcaneal (TC) fusion with talectomy, and, in severe cases, below-knee amputation. Total ankle replacement (TAR) currently is contraindicated in the face of talar AVN. The development of longstemmed talar prosthesis, which anchors into healthy calcaneal bone, may allow joint replacement in these challenging cases.

Arthroscopic Débridement and Core Decompression

Rationale

Similar to treatment strategies in AVN of the femoral head, core decompression for talar AVN is thought to enhance revascularization and decrease intraosseous pressure. It is typically recommended for the treatment of Ficat and Arlet stages I and II, which would represent partial AVN and those without collapse. Mont et al (38) reviewed 17 ankles (11 patients) that underwent core decompression with stage I or II classification according to Ficat and Arlet (38). They reported 14 ankles with excellent (11) and good (3) results and three ankles with poor results that required fusion. The investigators concluded that core decompression is a viable method of treating talar AVN before collapse. Delanois et al (53) reviewed 37 ankles; 29 had Ficat and Arlet stage II disease and eight had stage III or IV disease. Thirty-two ankles were treated with core decompression. Twenty-nine had fair to excellent clinical outcome at a mean follow-up of 7 years. The three remaining had an arthrodesis for failed core decompression.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree