CHAPTER 97 Surgical Treatment of Axial Back Pain

INTRODUCTION

Severe axial back pain represents one of the most challenging problems in spine surgery. Seventy to 85% of people have low back pain at some time. It is considered the second most common cause of appointments to physicians in the United States.1 The social and economic burden incurred by treatment of axial back pain is high and accounts for 2% of the gross domestic product.2,3 Surgical options remain controversial in spite of the fact that back pain producing lumbar degenerative disc disease is the most common cause of operative intervention on the spine. Though many treatments are in use, results have been somewhat unsatisfactory, even with aggressive fusion procedures.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Degenerative disc disease (DDD) has been defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by manifestations of disc degeneration and symptoms related to those changes. Disorders of the spinal motion segment are generally accepted to be a source of low back pain. Degenerative changes in components of the motion segment seem to be associated with release of nociceptor stimulating chemical mediators; cytokines, nitric oxide, phospholipase A2 and others have been implicated.4 Anatomically, there are several sources of nociceptors which include the facet joint capsules, perivascular tissue, periosteum, outer anulus, and major traversing roots and rootlets.5 In the authors’ experience, and that of others in the literature, the damaged posterior anulus is the most common source of axial back pain syndromes.6 The dorsal root ganglia, which house the sensory cell bodies, have been identified as a likely modulator of low back pain.5,7 Chronic injury has been shown experimentally to increase sensitivity to mechanical stimulation.8 Upregulation and downregulation of various neuropeptides has been associated with peripheral injury and it seems likely that similar changes occur with chronic peripheral nociceptive stimulation.9 The better understood in this group of axial back pain causes are disc herniation, radiographic segmental instability, and spinal stenosis. For these causes, there is a general agreement on basic approaches for diagnosis and treatment, though this is better defined when radicular symptoms are present. Less understood anomalies of the intervertebral disc as a source of low back pain include internal disc disruption syndrome, isolated disc resorption, and painful degenerative disc disease. In clinical practice ‘internal disc disruption syndrome’ as originally described by Harry Crock seems to run on a continuum with painful degenerative disc disease,10 the former being the most extreme manifestation and the latter, when asymptomatic, representing its antithesis. Why a similar-appearing lesion is well tolerated in many and severely disabling in some is not clear and thus the approach to diagnosis and treatment is often controversial.11

The number of fusions in the United States continues to rise yearly with over 50% being performed for symptomatic degenerative disc disease, or internal disc disruption syndrome (IDD) without herniation. IDD was first described as a pathological condition of the disc causing low back pain with or with out lower extremity radiation with minimal deformation of the disc anatomy.11 Historically, it was accepted that the intervertebral disc had no nociceptive ability and no innervations. Anatomic research has revealed that the outer layers of the anulus fibrosus and endplates are innervated from the sinuvertebral nerve branches and their rich innervations in the periannular connective tissue.4,9 As the disc undergoes degeneration, it loses its ability to convert nucleus compressive loads to tensile anulus loads, resulting in further stresses and degeneration of the endplates, facets, and anulus. In addition, disc degeneration may cause pain at other locations. Collapse of a degenerated disc may increase pressures on the facet joints, thereby leading to facet overload and painful facet arthropathy. A degenerated disc may also extrude nuclear material and irritative chemicals into nociceptive-rich locations such as the posterior lateral spinal canal, resulting in radicular-like pain.11

PRESENTATION DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL COURSE

Most cases of axial back pain resolve over time with conservative care. There is 70% spontaneous improvement after 5 years in a study of a group suffering from chronic low back pain. Eighty percent of the group that did not improve had other mitigating factors present, such as psychosomatic issues.12 Although the low back pain from degenerative disc disease usually improves spontaneously, a significant number of patients do not improve, and may even have worsening symptoms and disability. There are currently no reliable diagnostic methods differentiating disabling painful internal disc disruption syndrome from asymptomatic degenerated discs and there is disagreement on indications for fusion when compared to nonsurgical treatments. Clinical examination is usually characterized by low back pain with or without extremity radiation. The diagnosis of isolated, mechanical (activity and posture related) low back pain should only be made after first excluding less common conditions such as tumors, deformity, infection, ongoing neurologic injury, visceral disease, etc. Flexion postures such as sitting, forward leaning, and bending are typically aggravating due to increases in disc pressure in these positions. For most patients, lying recumbent usually relieves the symptoms. Some patients are intolerant of lumbar flexion to the extent that supine reclining increases pain that is only relieved when lying prone. The group that responds with diminished pain in lumbar hyperextension positions, in the authors’ experience, can frequently overcome symptoms by nonsurgical means. Maintenance of static postures is intolerable in many of the more severely afflicted patients. This is presumably related to viscoelastic creep of segmental soft tissues. Degenerative discs may be associated with referred, sclerotomal pain to the buttocks and lower extremity.

Plain films may be interpreted as negative or only show typical age-related disc degenerative changes such as endplate sclerosis, uncinate spurring, loss of disc height, and facet degeneration. Flexion–extension lateral views may reveal segmental instability not apparent on static films. When changes are primarily localized to one segment, there is a high likelihood that the segment is the source of symptoms. Spondylolisthesis or spondylolysis may be an incidental finding. It is also not uncommon that the segment above is involved and may be the cause of the back pain. In larger spondylolytic slips the discs are under tension instead of compression, and typically do not cause back pain without marked translational instability evident on bending films. Unfortunately, frequently there are multiple degenerative segments or none, which makes identifying the source of back pain more difficult. In evaluating pain due to disc degeneration, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most commonly employed modality since it can directly infer the degree of hydration in the nucleus pulposus. A degenerated disc will show the area of the nucleus pulposus to have decreased signal on T2-weighted images.13,14

First described by Zucherman et al.15 and more recently by Aprill and Bogduk,16 the presence of a high-intensity zone on T2-weighted MRI images correlates with a positive provocative discogram.15,16 However, recent studies have shown that in an asymptomatic group of volunteers who had a high-intensity zone on MRI, there was a 69% rate of false positives on discography.17 Small annular tears and tears that are not connected to the central nucleus may also evade MRI and discogram detection.16

Modic changes are another commonly used criterion to evaluate disc degeneration. Modic changes can be divided into three types. Type one reflects an acute disruption and fissuring of endplates, which leads to ingrowth of vascularized fibrous tissue into the marrow of the adjacent vertebral body. This tissue exhibits diminished signal on T1 images and increased signal on T2 images.18 In chronic degeneration (type two), the bone marrow undergoes fatty degeneration, thereby showing an increased T1 and an isointense T2 signal. Type three changes reflect extrinsic bone sclerosis, which is manifested as a decreased signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images. The most widely used diagnostic tool for identifying the painful degenerative disc disease is lumbar provocative discography. However, even these findings have been shown to not correlate well with the presence or absence of low back pain.

Discography provides information regarding pain response and pressure response, and gives details on the degree of annular disruption. However, the value of discography still remains controversial. There is a large variation in the patient’s pain response, patient’s mental state, and even the physician’s skill in performing the study. Historically, discography was first reported on by Lindblom in 194819 as a method to identify herniated discs in the lumbar spine. It was also noted that a reproduction of the patient’s usual sciatica sometimes occurred during injection of the contrast material. With subsequent use, it was noted that familiar back pain was sometimes reproduced during the test. The finding caused some to begin using the test to evaluate lumbar discs as the origin of patients’ chronic low back pain. From early use of discography, the meaning of a painful injection has been unclear. It is unknown if a disc that is painful when injected can be reliably designated as the cause of clinically significant low back pain. In an effort to improve the specificity of discography in diagnosing discogenic pain, some investigators have used additional criteria beyond pain reproduction on injection. The primary criteria for a positive disc injection are pain of significant intensity on disc injections and a reported similarity of that pain to the patient’s usual, clinical discomfort. Other clinical investigators have held more complex, stringent, and sometimes idiosyncratic criteria for positive injections including: negative control disc, concordant pain, dye penetration on injection, demonstration of pain behavior, maximum pressure on injection, and only one or two positive discs. Most clinicians require that at least one additional ‘control’ disc be examined. The control injection should ideally be ‘negative’ to confirm a positive study. It is not clear whether this means an adjacent ‘control’ disc injection must be ‘painless,’ or just not significantly painful in intensity. It is also not clear whether a painful but discordant disc satisfies the ‘negative control’ requirement. Most discographers have required that painful injection be considered negative if the sensation is clearly unfamiliar. On the other hand, it is not clear how exact a reproduction is required for a ‘positive test.’ Some investigators advocate that only an exact reproduction be accepted while others do not. Some investigators have maintained that dye penetration must extend to or through the outer anulus, scoring a ‘true’ positive injection in addition to the presence of pain with the injection. Others have indicated that ‘behavioral’ signs of pain such as guarding, withdrawal, or grimacing must accompany the presence of pain for the test to be considered positive. Finally, some have argued that pain elicited during low-pressure injections be considered positive because of the concern that high-pressure injections may cause deflection of the vertebral endplates or cause rupture of membranes over sealed and presumably asymptomatic fissures. Recent work has revealed a 10% false-positive rate among asymptomatic volunteers, with rates going up to 83% in volunteers with a diagnosis of an unrelated somatization disorder. Another study revealed up to a 40% positive pain reproduction following discography performed in asymptomatic patients who had prior discectomies. In another study, a group of patients without low back pain who had recent posterior iliac crest graft for nonspine-related procedures underwent discography. Fifty percent of patients experienced pain that was similar to or an exact reproduction of pain at the iliac crest bone graft harvest sites.1,17,20–27 These results question the ability of patient to separate spinal from nonspinal sources of pain on discography. Provocative discography purports to identify a subgroup of low back pain syndromes in which the primary cause of the patient’s symptoms is the disc itself, apart from any other structural or psychological processes. By this theory, the successful alteration of the offending disc and solid arthrodesis or arthroplasty should result in outcomes equal to those achieved for spinal fusion with known primary structural pain generators such as unstable spondylolisthesis. However, discography studies have shown that discographic pain response can be of significant intensity in discs not actually causing the patient’s primary pain. Also, certain ‘asymptomatic discs’ are more likely to be painful on injection, such as discs with annular fissures or discs after prior surgery. Studies also revealed that individuals with certain psychosocial characteristics are more likely to report higher pain intensity levels with disc injections than others, such as those with psychological stressors, chronic pain states, litigation involvements, and so forth. The failure to achieve consistent clinical success after spinal fusion for presumed discogenic pain is usually attributed to the morbidity of surgery or poor patient selection. Therefore, in the patient with a single arthritic or annular disrupted lumbar segment, without emotional troubles, with a stable family and occupational support, no history of chronic or unexplained pain syndromes and any compensation issues, discography may be helpful in confirming that the disrupted segment does hurt while the adjacent segments do not.1,17,20–28 We recommend, that discography be performed by those experienced in the technique and surgical ramifications, using strict criteria for interpretation. Furthermore, discography results need to be correlated carefully with the clinical history and physical examination to avoid surgical failures.

TREATMENT

The vast majority of patients with painful degenerative disc disease can be managed nonoperatively. The first task is to optimize the patient’s physiologic status. This involves increasing cardiovascular fitness and placing the patient in a smoking cessation program. Most patients with painful disc disease have exacerbation of symptoms with flexion, so extension exercises as well as low-impact aerobic exercise such as swimming and cycling are helpful if tolerated in a conditioning program. In the authors’ experience, isometric neutral stabilization and hyperextension exercises are commonly effective. Robin McKenzie has pioneered and refined extension-based stabilization. It is the authors’ belief that instruction in minute-by-minute comprehensive daily body mechanic control and posture management can diminish the repetitive stimulation of the damaged section of the disc anulus and facilitate recovery in some patients. Back pain and work loss is less in people who maintain a regular exercise regimen. Hip and hamstring stretching, buttock and abdominal strengthening, and hyperextension exercises to strengthen the gluteus and paravertebral muscles are frequently successful in controlling symptoms.29,30

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication and acetaminophen can provide improved symptoms in some patients. Muscle relaxants may have an effect in treatment of acute flares of low back pain symptoms but are not recommended for chronic use.29,30

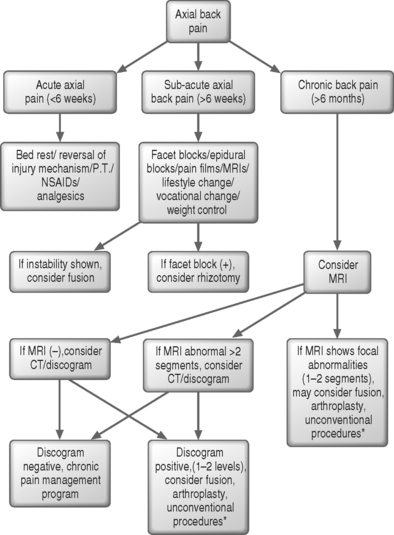

In general, operative intervention is only offered to patients where surgery is expected to improve the results of the natural course of the disease (Fig. 97.1). In these patients, disability is great and no indication of nonsurgical recovery is suggested by history. Discectomy has been performed in the past for treatment of patients with incapacitating low back pain from painful degenerative disc disease. Currently, there is no accepted indication to treat degenerative disc disease with isolated discectomy. Discectomy is indicated for a patient with incapacitating radicular symptoms resulting in compressive neuropathy from a herniated nucleus pulposus which is progressive or which has failed a 6-week trial of nonoperative treatment. Symptoms may include incapacitating sciatica (extremity pain) with or without a neurologic deficit. The patient may have low back pain in concert with these symptoms but axial back pain as a primary complaint is a relative contraindication to discectomy, which may or may not relieve back pain. We suspect the larger the protrusion is more likely to have a favorable response for isolated back pain.

There have been a variety of disc debulking procedures described over the years as a less-invasive means to eliminate symptoms resulting from compressive neuropathy without the morbidity known to occur with conventional discectomy procedures. They have not to date been shown to be effective for axial back pain without neural compression. Chemonucleolysis as a treatment for patients with low back pain (primarily from herniated discs) was originated by Thomas, who noted that a proteolytic enzyme called papain had affinity for the ground substance (i.e. proteoglycans) of all cartilage in the body. Many studies in humans during the 1970s led to chymopapain being implanted in over 16 000 patients before FDA approval was granted.31,32 However, chemonucleolysis fell out of favor.33 First, multiple studies demonstrated the superiority of surgery over chymopapain injection.34 Ziegler reported in 126 patient a 98% success rate for patients undergoing surgical excision versus a 60% success rate for patients receiving chymopapain. Furthermore, chemonucleolysis actually caused recurrent low back pain in 54% of the patients, compared to only 5% receiving surgery.35 Watters et al. also demonstrated a superior patient satisfaction with surgery. This group reported a disturbing rate of sequestered disc herniation in the chemonucleolysis group requiring reoperation.36 The second factor leading to the decline of chemonucleolysis related to the fact that there is no significant alteration of the natural history of a lumbar disc herniation treated conservatively when compared to one following chymopapain injection. In part, this is related to the fact that patients with a large disc herniation have much poorer results than do patients with lumbar disc bulges or protrusions (i.e. disc contained in the anulus). Finally, there were unique complications with chymopapain use,37–39 such as anaphylactic responses and unpredictable neurologic deficits. Anaphylactic shock was reported to be as high as 1 in 5000. Agre reviewed the neurologic complications following chymopapain injection and found cerebral hemorrhage, seizures, paraparesis, paraplegia, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and death.39

Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy (APLD) has been used for some time as a minimally invasive variation of open discectomy. The working principle is that removing a portion of the nucleus pulposus relieves the intradiscal pressure, thereby alleviating irritation in the nerve root and the nociceptive fibers in the anulus fibrosus. Even proponents of this procedure recommend that APLD be limited to contained disc protrusions. Relative to the natural history of a herniated disc, APLD in several studies has not provided superior results though morbidity is quite low. Furthermore, there is a lack of well-constructed scientific studies evaluating its effectiveness.33,40

Other minimally invasive procedures include percutaneous laser nucleolysis of the intervertebral lumbar disc and percutaneous disc decompression with electrothermal nucleoplasty. In the hope of avoiding intraoperative trauma to dura and nerve roots, and preventing intraneural and perineural scar formation when approaching lumbar discs, Nerubay et al. used a carbon dioxide laser to vaporize a protruding nucleus pulposus.41 After performing an initial trial in dogs to determine the amount of laser energy necessary to vaporize the nucleus pulposus, a prospective study of 50 patients was performed. Good and excellent results were achieved in 74% of the patients, with four patients requiring subsequent operative intervention. Patients with sequestered fragments or bony lateral stenosis did not benefit from the procedure. Four complications of nerve root irritation (three which resolved) were attributed to thermal damage cause by warming of the cannula.42 The authors, however, were careful to point out that strict patient selection is crucial to the outcome. Proponents of percutaneous nucleoplasty claim that the use of radiofrequency (RF) energy removes nucleus material and creates small channels within the disc. Using this coblation technology, coagulation and ablation are combined to form channels in the nucleus and theoretically decompress the herniated disc. A recent study on three fresh human cadavers measured intradiscal pressure at three points: before treatment, after each channel was created, and after treatment. The results revealed that intradiscal pressures were markedly reduced in young cadavers, while it changed very little in older specimens.43 Further studies with animal and prospective human trials are needed before any conclusions can be reached about the clinical efficacy of the technique.

The wide abdominal rectus plication (WARP) is another procedure for axial back pain.44 The WARP abdominoplasty is based on the theory that contraction of the abdominal muscles via the attachments to the lumbodorsal fascia results in abdominal wall stiffening, increased intra-abdominal pressure, and resultant diminished intradiscal pressure. When a ‘stretched out’ or an adynamic segment exists in the anterior abdominal wall (such as with some women following pregnancy), the internal oblique and transverses abdominus are not at physiologic length. This laxity prevents maximum force generation with contraction and thereby weakens abdominal support that is usually present via the attachments to the lumbodorsal fascia. The surgical procedure involves plicating the right side to the left side of the rectus fascia, thus converting the flat rectus muscle into a tube. This diminishes trunk girth and reduces abdominal cavity size and therefore tightens the anterior abdominal–lumbodorsal fascia muscle complex. In the largest series reported to date, the author reported increased height in the intervertebral space on both the MRI and on lateral spine radiographs postoperatively in all 25 patients. The back pain was reduced postoperatively in all except one patient. The author limited the inclusion criteria to patients with a positive abdominal compression (TAC) test, weak internal oblique-transversus abdominus Cybex muscle test, and to those patients with back pain undergoing elective abdominoplasty. The TAC test involves applying manual pressure to the abdomen, which gives relief in some patients. The procedure may be a consideration in patients with abdominal wall insufficiency, relief with abdominal corset or binde, and or a positive TAC. The authors have had some success in a consecutive series of 23 selective patients.

The literature provides success rates varying from 17% to 92% with surgical fusion.45–53 Many techniques have been utilized and range from the simple posterior fusion without bone graft to most extensive anterior–posterior fusion with pedicle instrumentation. The goal of the operation is to limit sensory stimuli and tissue inflammation across the segment by stopping mechanical motion.11 Since the patient population likely have facilitated segmental and/or central nervous system (CNS) nociception, complete obliteration of motion is the goal.

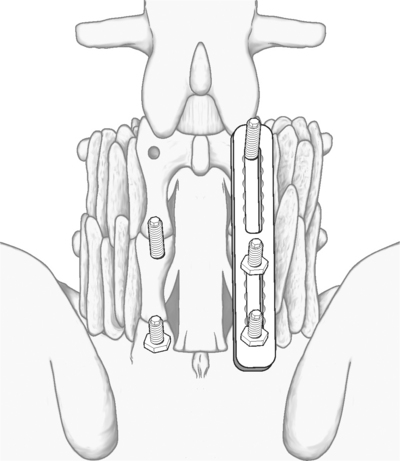

Traditionally, posterolateral fusion has been the standard surgical technique. Success rates have been variable and reported as high as 90% using rate of apparent solid fusion and removal of pain and return to work as criteria. Poor results are associated with pseudoarthrosis, workman’s compensation and being out of work longer than 3 months.54–59 Pedicle screw instrumentation has been added to the procedures to decrease nonunion rates (Figs 97.2, 97.3). Recent studies have shown that adding instrumentation increases fusion rates by 20%.59–65 Also, proponents of instrumentation feel that these constructs offer immediate stability and allow an expedited postoperative recovery (Fig. 97.4). Current practice for painful degenerated discs among many surgeons is posterolateral fusions augmented with pedicle screw instrumentation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree