CHAPTER 28 Surgical Hip Dislocation for Femoroacetabular Impingement

Introduction

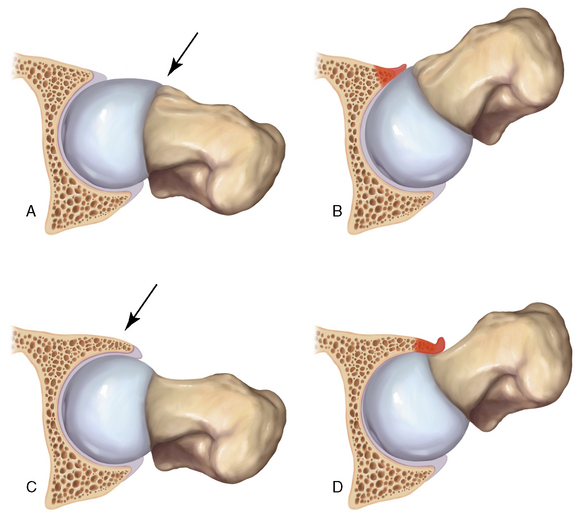

Two distinct mechanisms of FAI have been described; these are commonly referred to as cam disease and pincer disease (Figure 28-1, A through D). The descriptions of these conditions were based on the skeletal morphology and the pattern of chondrolabral damage observed during surgical hip dislocations. However, these morphologic patterns are not mutually exclusive; it is quite common for patients to have components of both cam and pincer types of impingements. With cam FAI, there is an abnormal bony prominence at the femoral head–neck junction that is often located anterosuperiorly. During hip flexion, the abnormal contoured femoral head engages the anterosuperior acetabulum and produces shear forces that lead to chondral abrasion, delamination, and, eventually, full-thickness cartilage loss. The natural history of this impingement process is initially acetabular cartilage injury, which is followed by labral injury and ultimately joint arthrosis. At first the labrum is uninvolved, but, with further impingement, labral injury results from the further loosening of the labrum at the transition zone between the peripheral cartilage and the labrum itself. With pincer FAI, there is increased acetabular coverage that leads to linear contact between the femoral head–neck junction and the acetabular rim. Acetabular overcoverage may be either generalized, as in coxa profunda and protrusio acetabuli, or localized, as in acetabular retroversion and anterior acetabular overhang. Unlike what occurs with cam FAI, the labrum is the first to get injured with intrasubstance degeneration, cyst formation, and bone apposition at the rim, which further deepens the socket and exacerbates the problem. The prominent acetabular rim abuts with the femoral neck and causes the femoral head to lever in the acetabulum. This chronic levering of the head generates shear forces and injury to the posterior cartilage. Over time, this contrecoup mechanism leads to posteroinferior chondral damage and joint space narrowing.

Treatment, indications, and contraindications

The most important indications for FAI surgery are physical examination and radiographic findings that are consistent with FAI (Box 28-1). Proper imaging studies are critical to confirm and quantify the deformity and to assess the degree of arthritis. Unnecessary treatment delays also should be avoided.

History and physical examination

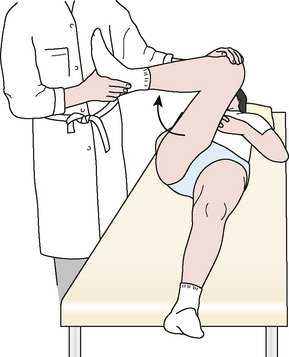

It is crucial that all FAI patients receive a thorough physical examination, because there are many extra-articular diagnoses that can present with hip pain. The examination begins with detailed motor and sensory examinations. Next, the range of motion is assessed. Limited internal rotation of the flexed and adducted hip is seen in both cam and pincer FAI, but a greater loss of internal rotation is seen with cam FAI. This is followed by FAI-specific tests. An impingement test (Figure 28-2) is performed with the patient in the supine position; the affected hip is adducted and internally rotated as it is passively flexed. In patients with FAI, the femoral head–neck junction and the acetabulum abut, thus producing shear forces on the labrum and reproducing a sharp pain in the groin. A posteroinferior FAI test is performed with the patient supine on the edge of the examination table with the legs dangling free from the end. The examiner then extends and externally rotates the affected hip. Deep-seated groin pain during this maneuver is indicative of posteroinferior FAI, and it is frequently combined with limited external rotation. Finally, other critical examination maneuvers are performed to find associated pathology of the psoas, the iliotibial band, the lower back, and other related structures.

Imaging

After the adequacy of the radiograph has been verified, it should be reviewed in a systematic fashion. First, the radiograph should be assessed for the coverage of the femoral head (i.e., center edge angle and Tönnis angle) or for gross arthritic changes (i.e., Tönnis scale). Next, the acetabulum should be inspected for pincer-type FAI. Five radiographic structures must be identified: 1) the medial acetabular wall; 2) the ilioischial line; 3) the anterior wall of the acetabulum; 4) the posterior wall of the acetabulum; and 5) the femoral head. By understanding the relationship of these radiographic structures, all of the common causes of pincer FAI can be diagnosed. In a patient with coxa profunda, the medial acetabular wall approaches and overlaps (if it does not pass medial to) the ilioischial line, which causes a deep socket. In a patient with protrusio, the femoral head is medial to the ilioischial line. In a patient with true acetabular retroversion, the anterior and posterior acetabular walls overlap; they also have a positive crossover sign and a prominent ischial spine (Figure 28-3, A). In these cases, there may or may not be a sufficient posterior wall, but there is always a relative anterior overhang. Finally, one must assess for os acetabuli, which can represent either broken pincer lesions or unfused portions of the acetabulum (i.e., true os acetabuli).

On the femoral side, cam FAI is readily diagnosed with the proper radiographs. Given its mostly anterosuperior location, the cam lesion is often underappreciated on a standard anteroposterior radiograph, and it may be obstructed by the greater trochanter on a frog-leg lateral view. The aspheric head–neck junction is best visualized with either a 45-degree Dunn view or a cross-table lateral view with the leg in 15 degrees of internal rotation. The Dunn view, which is also known as an extended neck lateral view, is taken with the patient’s hip in neutral rotation, flexed 45 degrees, and abducted 20 degrees. The internally rotated cross-table lateral view is often more practical for routine use, because positioning the patients for the Dunn view requires a leg holder or an assistant. Either image can be used to measure the head–neck offset and the alpha angle, both of which are abnormal parameters that can be used to assess cam FAI (see Figure 28-3, B). In addition, the femoral neck shaft angle should also be assessed for any significant varus deformities.

In addition to radiographs, we routinely obtain a magnetic resonance arthrogram to accurately assess chondral delamination and full-thickness cartilage defects. In many cases of FAI, hips that produce normal radiographs (as defined by Tönnis grade) in fact have extensive chondral injury. Magnetic resonance imaging also assesses for labral pathology or subtle signs of FAI, such as fibrocystic changes at the head–neck junction; these changes are also known as synovial herniation pits. The magnetic resonance imaging should involve the use of cartilage-specific sequences, and it should be performed in radial-directed sections for the accurate measurement of angulation and the translation of the impingement lesions in the radiologic reference planes (Figure 28-4). Standard magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis is often less sensitive, because it does not occur in the correct sequence plane with a resolution being far too low. In addition, although computed tomography scans provide a superior assessment of femoral anteversion, acetabular version, and femoral offset, they require radiation exposure during 20 radiologic pelvic overviews; thus, computed tomography should be used quite judiciously. Other advantages of obtaining a magnetic resonance image include the evaluation of stress fractures and soft-tissue abnormalities as well as the measurement of the alpha angle and acetabular version.

Surgical technique

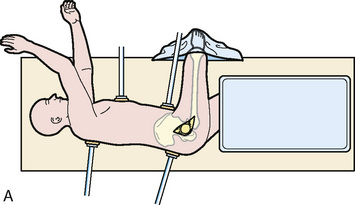

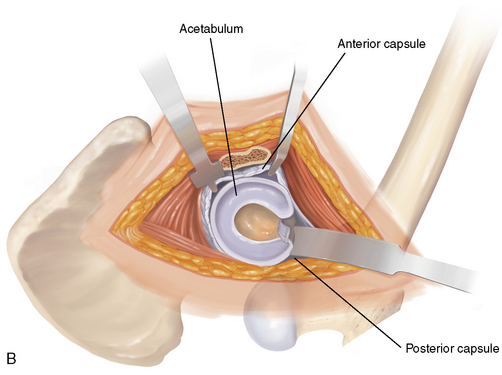

General or spinal anesthesia is used. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position in well-padded bolsters, and care is taken to also protect the nonoperated limb. Correct orientation is important to allow for the accurate assessment of acetabular orientation during the procedure. The skin is cleansed with a standard preparation solution over the trochanteric region. The patient is prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion (Figure 28-5, A) with a free leg sterile bag drape placed on the opposite side of the operating table to receive the lower leg during hip dislocation (see Figure 28-5, B). A second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic is given for prophylaxis and continued for 24 hours. Image intensifying and laser Doppler flowmetry are not routinely used, but both can be helpful for either osteotomy fixation or to monitor the perfusion of the femoral head.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree