Surgical Handling and Local Flap Coverage for Distal Amputations, Skin Loss, and Nail Bed Injuries

Raymond A. Wittstadt

Helen G. Hui-Chou

INDICATIONS

Tissue loss and amputations of the fingers are among the most common injuries encountered in the emergency room. A 1982 survey of emergency departments across the United States by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found that 25.7% of its workload was caused by occupational digit injuries. These injuries have considerable social and economic impact and can lead to prolonged lost time from work. Unfortunately, treatment of these injuries is often relegated to the least skilled or experienced providers. We believe that careful consideration and discussion of the treatment options can improve functional outcomes and minimize lost time from work.

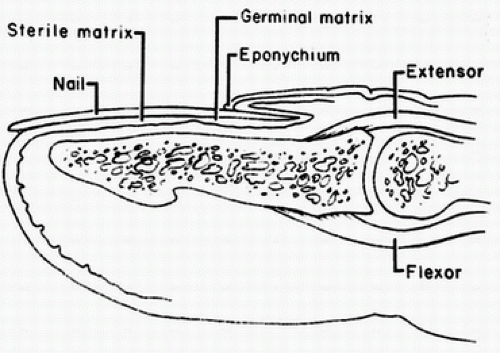

By convention, the fingertip is that portion of the finger distal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and tendon insertions. It is a complex anatomic area with almost all appendicular tissue types represented and vulnerable to injury. The volar pulp consists of highly innervated glabrous skin and subcutaneous fat anchored by fibrous septa. The dorsal surface perionychium contains the nail plate; nail bed, with sterile and germinal matrix; and specialized eponychium, paronychium, and hyponychium (Fig. 29-1).

Goals of treatment in fingertip injuries include preservation of adequate sensation while minimizing neuroma tenderness, provision of durable skin coverage, prevention of proximal joint contractures, early return to work, and maximum finger length consistent with the above.

Many techniques have been utilized over the years to address injuries and tissue loss in the fingertip. There is no one best way to handle every injury and treatment must be individualized. Each injury may have several solutions. The hand surgeon must fully evaluate each patient’s occupation, hobbies, circumstances surrounding the injury, and emotional attitude regarding treatment options. Frank discussion of recovery times for the various treatment options along with expected outcomes usually results in a mutually agreeable solution.

Indications for replantation of a digit at the distal phalanx level are still controversial. Some indications include amputation proximal to the lunula, since no other procedure can salvage the nail. Replantation may be valuable for musicians, business people, and others exposed to the public in their occupations or for those requiring specialized use of the fingertip. A strong indication exists for children because of social and psychological implications. Lastly, the surgeon must consider the patient’s age, presence of systemic disease, level and type of amputation, and patient motivation before replantation is selected. Replantation can avoid a resulting painful stump when compared to revision amputation (1). However, some considerations of replantation outcome must be addressed. Hattori found that aesthetic appearance may be unsatisfactory due to pulp atrophy and nail deformity. Recovery of sensation may be decreased with only recovery of protective sensation. The average total cost of successful replantation was five times more than the cost of amputation and closure. Replant patients had a longer hospital stay and longer time off work (2). Replantation of the distal part has been shown by Wang et al. to have longer return to work, inferior sensation, and active range of motion. Replantation may be considered only after careful discussion with each patient regarding quality of life (3).

Causes of fingertip injuries fall into three main categories: crush, laceration, and avulsion. Crushing is caused by the application of pressure to the fingertip, crushing the structures or pinching with enough force to cause amputation. Catching the fingertip in a machine or door is typical of this mechanism. Lacerations occur with sharp objects such as a knife or saw. Laceration is a common component of essentially all open distal tip injuries. The amount of tissue trauma, contamination, and orientation of the laceration or tissue loss will significantly influence the reconstructive options. Avulsion occurs when tissue is removed by tangentially applied forces or distraction. Machine “roller injuries” are typical examples of avulsion trauma. This mechanism of injury, with its traction force, may present a greater zone of injury than is initially apparent due to more proximal damage to vessels and nerves.

Cleanly amputated fingertips at or proximal to the DIP joint can be considered for replantation. Crushed or avulsed tissue is rarely suitable for replantation but can occasionally be used as a skin graft or composite graft when multiple digits have been traumatized.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Absolute contraindications to any one technique cannot be given. However, some relative contraindications should be considered. Rotation or advancement flaps should be used with caution, or not at all, in patients with vascular disorders such as Raynaud’s disease, renal failure, some connective tissue disorders, or inflammatory arthropathies. Coverage alternatives that require an extreme flexed posture or lengthy immobilization must be weighed against potential joint contractures. Heroic efforts to salvage nearly unreconstructible injuries with multistep operative plans requiring complex tissue transfers must be balanced against ultimate functional and cosmetic concerns.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Operative planning begins with the patient’s presentation in the emergency room. It is appropriate to perform and document an evaluation of the entire patient, particularly health status related to diabetes, vascular disease, and smoking. An expanded history should include mechanism and time of injury, whether the hand was caught in a machine, and if so, for how long, appropriate past medical and hand injury history, medications, and allergies. Hand dominance, occupation, and

nonoccupational activities should be noted as well. Tetanus status should be determined and not overlooked.

nonoccupational activities should be noted as well. Tetanus status should be determined and not overlooked.

Examination requires complete careful removal of all dressings. This can be painful, but sensation in the injured area must be determined before any local anesthesia is administered. Once sensation has been evaluated and documented (two-point discrimination may be the most available and logical objective data to record), local anesthesia can be given to provide relief and facilitate further evaluation of the injury. Examination of amputated tissue, if available, should also be performed. Factors such as angle of tissue loss, function of adjacent joints and tendons, nail involvement, and amount of exposed bone should be noted.

Standard x-ray views are mandatory for all fingertip injuries. The amputated tissue should also be imaged in cases in which replantation or use of the amputated part for graft purposes is contemplated. Because a crushing mechanism is the cause of many distal tip injuries, it is important to check for fracture lines that may extend proximally into the joint and evaluate the degree of comminution of the involved segment. The bony injury often limits or influences the ultimate treatment choice.

Some consideration should be given to the venue and circumstances in which many of these procedures are performed. As noted previously, care for tip injuries should not be assigned to trainees or less experienced physicians. The permanency and importance of the results requires greater attention and involvement by the attending hand surgeon. Many of these procedures can be safely, effectively, and efficiently performed in a well-stocked and staffed emergency department. Appropriate equipment, lighting, anesthetic capability, and manpower are all important variables that determine whether this is feasible. It is never wrong to take a distal tip injury to a formal operating room, especially when multiple digits are involved or the flexor side is significantly traumatized. If there is any doubt about the level of care that can be rendered in a particular venue, then defaulting to the safest, most controlled environment will yield optimal results.

Unless there are exposed joint surfaces, tendons, or neurovascular structures, definitive treatment can usually be delayed by initial mechanical debridement and irrigation, followed by the application of Xeroform Petrolatum dressing (Sherwood Medical, St. Louis, MO) or similar ointment dressing. There may be a benefit to delaying definitive treatment to assess the viability of traumatized tissue. In many cases, amputation may be the favored treatment after an initial assessment. However, if the digit is cleaned and dressed in the emergency department, later evaluation by the surgeon, consideration by the patient, and the “test of viability” afforded by reflection of 24 to 72 hours may alter the decision in favor of a reconstructive option over ablation.

Although this chapter focuses on local flaps for fingertip coverage, all techniques should be considered. Factors influencing the choice of techniques include the angle of tissue loss, amount of exposed bone, condition of the amputated part (if available), injuries to adjacent fingers, digit involved, size and location of defect, and patient wishes. Treatment principles should include preservation of all viable tissue and utilization of amputated parts. In general, it is best to choose the simplest procedure consistent with individual factors and goals of treatment.

A reconstructive ladder is a consistent image to maintain when considering the options available to treat distal tip amputation. The steps up the ladder reflect increasing complexity of the reconstructive effort. The range of treatment alternatives includes healing by secondary intention, shortening and primary closure, skin grafting (split or full thickness), replacement of the amputated part with microsurgical techniques or a nonvascularized composite graft, or flap reconstruction. Flaps that are attractive and useful for treating fingertip injuries include local, regional, or distant flaps.

TECHNIQUES

Nail Bed Injuries

Nail bed injuries may involve underlying distal phalanx fractures. Subungual hematomas may indicate extent of underlying involvement. Traditionally, hematomas larger than 50% of the nail bed surface were thought to require nail plate removal and formal repair. However, recent studies have called this into question. Recent studies have modified current operative management of nail bed injuries. Seaberg et al. looked at 45 children with fingertip injuries. Over half of the children had subungual hematomas greater than 50% of the nail bed surface area and 30% had fractures (4). All were treated with trephination alone. Follow-up at 10 months revealed no complications. Performing randomized trials for this injury is difficult, but Gellman (5) did a prospective study of 53 patients, ages 1 year to 20 years old, with 26 consecutive patients receiving formal repair and 27 undergoing trephination or no treatment. One-third of cases had subungual hematomas greater than 75% of the nail. There was no difference in outcomes at 2-year follow-up. However, the cost of nonsurgical

treatment averaged $283, while nail bed repair costs averaged $1,263. Costello and Howes (6) found no evidence to support the use of routine antibiotics for subungual hematomas.

treatment averaged $283, while nail bed repair costs averaged $1,263. Costello and Howes (6) found no evidence to support the use of routine antibiotics for subungual hematomas.

Formal nail bed repair is still appropriate in patients with displaced fractures of the distal phalanx or injury to other portions of the dorsal fingertip. Repair of lacerated paronychium, eponychium, or hyponychium should be done with fine absorbable suture such as 6-0 or 7-0 chromic. Strauss et al. have found that nail bed repair with 2-octylcyanoacrylate (Dermabond) had similar cosmetic and functional results and was faster than suture repair (7,8). Nail plate removal to accomplish this is often needed and the removed nail plate or other material, such as a suture pack foil, should be placed under the eponychial fold to minimize scar formation between the fold and the germinal matrix. The foil or nail plate should be trephined centrally prior to replacement and can be sutured in place as necessary with absorbable suture. We prefer not to use nonadherent gauze for this purpose. If the amputated or avulsed part is available, it should be carefully inspected for specialized tissue that can be utilized as a full-thickness skin graft. Loss of eponychium will cause a permanent deformity of the nail fold and effect subsequent nail plate growth. If the amputated dorsal tissue is not available, careful consideration of how to reconstruct this area is needed if length is to be maintained. Split-thickness grafting from an adjacent finger (less common) or toe (more common) can be used, but donor site cosmetic deformity should be discussed with the patient.

Distal Phalanx Fracture

Many fingertip injuries have associated fractures of the distal phalanx. Frequently, these are minor or minimally displaced, and even if highly comminuted, they are usually stable due to the fibrous septa of the surrounding tissue. They do not require specific treatment other than protective splinting. However, significantly displaced or unstable fractures of the diaphysis or articular surfaces should be stabilized. Utilization of an appropriate gauge hypodermic needle can be hand drilled across these fractures in the emergency room or operating room, preferably under mini C-arm guidance, and does not usually need to cross the DIP joint. K-wires or miniscrew fixation can be used if needed to stabilize large articular fragments. Fingertip injuries with accompanying fractures can have prolonged recovery times. DaCruz et al. (9) found that 6 months postinjury, only 17% of patients with tuft fractures had fully recovered, with many patients experiencing some residual numbness, cold sensitivity, or hyperesthesia.

Epiphyseal fractures of the distal phalanx require special consideration, especially in children. Seymour’s fracture is an extra-articular transverse fracture of the base of the distal phalanx. Prior to closure of the epiphysis, this fracture will clinically mimic mallet deformities as the terminal extensor tendon inserts into the epiphysis only, although the fracture does not involve the DIP joint articular surface. The fracture is usually open and is prone to infection unless debrided. Other problems associated with Seymour’s fracture include incomplete reduction due to interposition of a bucket-handle flap of nailfold skin, fracture instability after removal of the nail plate, premature closure of the epiphysis, and dorsal rotation of the epiphysis. Al-Qattan (10) also noted that this fracture can also occur in adults. These fractures can be treated by closed reduction and splint or open reduction and K-wire fixation.

Healing by Secondary Intention

Open treatment, or healing by secondary intention, results in healing by the re-epithelialization of granulation tissue and wound contracture. It is most useful in children and for defects of modest size (1 to 1.5 cm or less) or tangential injuries with variable levels of tissue loss. This treatment is simple to perform and “burns no bridges” because any reconstructive option can still be elected after an initial period of observation. It arguably provides the best sensation, and healing time is comparable to that of other methods. Complications are rare, including an almost nonexistent infection rate, but stump tenderness can occur and cold intolerance is common with all types of finger trauma. Like all tip injuries in which the distal phalanx is involved, if there is any unsupported nail bed, a hook nail deformity may result.

Primary Closure with Digital Shortening

Primary closure, when possible, is simple and provides good sensation, rapid healing, and early mobilization. The nail bed should be trimmed to the level of the bony injury and should not be relied upon to cover exposed bone, which inevitably leads to hook nail deformities. Bone should be trimmed to achieve a tension-free closure and insure adequate soft-tissue padding over the bone. Preservation of tendon insertions is helpful to maintain motion and strength. Care should be taken to prevent excessive stump tenderness by trimming nerve ends at least 1 cm proximal to the level of the bony injury.

Skin Grafting

Although favored by some surgeons involved in care of the hand, skin grafting is rarely used at our institution for reconstruction. It is inferior in the key parameters that are of greatest consideration in this common injury.

Skin grafts are associated with lack of durability, diminished sensibility, hyperpigmentation, asymmetric contraction, and potential donor morbidity. Almost any of the other options discussed will yield superior results to even a well-performed skin grafting procedure.

However, split- or full-thickness skin grafts can be used to cover defects considered too large to heal by secondary intention or those not felt to be candidates for the other coverage alternatives. Survival of a skin graft requires that the area on which it is placed has sufficient blood supply to support the transplanted skin. Exposed bone, cartilage, or tendon typically does not meet this requirement.

Skin texture and color match should be considered. When possible, glabrous skin from the hypothenar area or foot should be used. If primary closure of the donor site is not possible, it too can be skin grafted. If nonglabrous skin is used, avoid donor areas that are hair bearing. Glabrous skin from the amputated part, if available and not too damaged, can be used as well. When glabrous skin is used, the appearance can be quite satisfactory, but sensation is inferior to healing by secondary intention or primary closure.

Composite Grafting

Replacement of the amputated part as a nonvascularized composite graft works best in children younger than 2 years of age. Results become increasingly unpredictable as the child approaches 8 and this appealing technique has little chance of success in older children or adults. Graft failure may delay recovery, but the tissue often serves as a biologic dressing as the tip reepithelializes. Microvascular replantation at this level may provide the best appearance, but it is technically demanding. Nerve recovery and sensation are variable after replantation, and decreased joint motion may limit functional recovery.

Regional flaps that will not reach to the fingertip, distant random flaps, and microvascular free flaps will not be discussed further, but they should be considered when appropriate.

Local Flaps for Fingertip Coverage

By definition, a flap consists of skin with varying amount of underlying tissue. Unlike skin grafts, this tissue receives its blood supply from a source other than the tissue on which it is placed. Flaps that receive their blood supply from many minute vessels in the subdermal or subcutaneous plexus are termed “random” flaps. Flaps that receive blood via a single vessel are termed “axial.” Local flaps available for fingertip coverage include both types. Flaps are also classified as homodigital, from the same digit, or heterodigital, from an adjacent digit. Reconstruction with flaps may be done as a single-staged or multiple-staged procedure.

Digital tip amputations with exposed bone can be treated by several methods already described, but local flaps are attractive because of their proximity, tissue match, possibility of enhanced function, sensibility, and acceptable complication profile. Typically, if bone length has been preserved, then the use of local flaps is appropriate. Flaps to be discussed in detail include volar V-Y advancement, lateral V-Y advancement, volar flap advancement, thenar flap, cross-finger flap, and homodigital island flap.

Volar V-Y Advancement Flap The volar V-Y advancement flap was first described in 1970 by Atasoy and Kleinert for most tip amputations with exposed bone, especially transverse or dorsal oblique amputations. Volar oblique amputations may not have adequate skin for this technique. As a general rule, in order to be a candidate for a V-Y advancement, 50% of the skin of the distal tip must remain, as measured by assessing the distance between the proximal most aspect of the wound and the DIP joint flexion crease.

This procedure can be done in the emergency room setting if all of the necessary equipment is available. Digital block anesthesia is used; we prefer Marcaine 0.5% administered via a single midline injection into the subcutaneous tissue at the base of the finger. While use of local anesthesia with epinephrine is increasingly popular, its use in this type of procedure may limit assessment of flap vascularity.

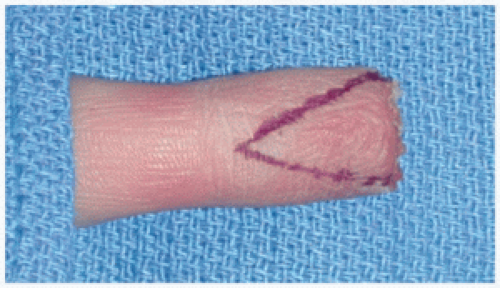

The size of the defect at the tip is measured or a pattern from the inner sterile glove wrapping is made. This is then transferred to the volar distal pulp that is to be advanced. A distally based triangle is drawn around the pattern. The apex of the triangle should be at the DIP joint flexion crease

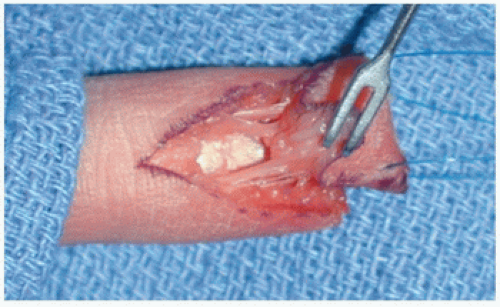

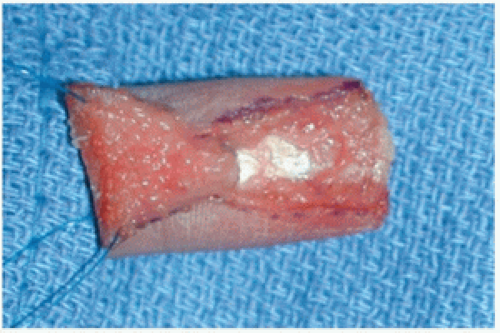

(Fig. 29-2). The skin is incised. Blunt dissection with sharp scissors is done to isolate the radial and ulnar digital neurovascular bundles (Fig. 29-3). All subcutaneous tissue except the bundles must be divided to allow tissue advancement. The deep fibrous septa between the flap and the underlying distal phalanx must be cut as well. This should free up the flap completely so that only the bundles remain as attachments (Fig. 29-4). At this point, the Penrose tourniquet is released to check flap viability.

(Fig. 29-2). The skin is incised. Blunt dissection with sharp scissors is done to isolate the radial and ulnar digital neurovascular bundles (Fig. 29-3). All subcutaneous tissue except the bundles must be divided to allow tissue advancement. The deep fibrous septa between the flap and the underlying distal phalanx must be cut as well. This should free up the flap completely so that only the bundles remain as attachments (Fig. 29-4). At this point, the Penrose tourniquet is released to check flap viability.

An alternative to raising the flap is to first mobilize the deep portion from the distal phalanx and flexor sheath by dividing the fibrous septa. The importance of this step, regardless of ultimate technique, cannot be overstated. By then controlling the injured edge of the volar skin with two skin hooks and providing longitudinal traction, sharp dissection of the skin and underlying tissue mobilizes the flap. In this version, the terminal branches of the nerve and vessel are not directly isolated or even visualized consistently. The contact of the knife blade to the fibrous tissue under tension must be trusted to divide the correct tissue and spare the other vital structures. The more experienced the surgeon becomes at raising this flap, the more appealing this option may present, as it may limit further flap trauma caused by excessive spreading or skeletonizing the neurovascular bundles.

FIGURE 29-5 Volar V-Y flap. The flap has been advanced distally to cover the tip defect. The resultant defect has been closed, converting the V defect to a Y. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree