CHAPTER 87 Surgical Decompression for Spinal Stenosis

DEFINITION

Lumbar spinal stenosis is an abnormal narrowing of the osteoligamentous vertebral canal and/or the intervertebral foramina, which is responsible for compression of the thecal sac and/or the caudal nerve roots; narrowing of the vertebral canal may involve one or more levels and, at a single level, may affect the entire canal or a part of it.1 Thus, abnormal narrowing of the spinal canal may be considered as stenosis if two criteria are fulfilled: the narrowing involves the osteoligamentous spinal canal, and it causes compression of the neural structures.

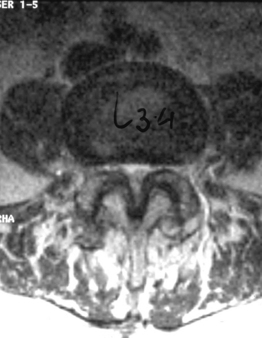

The second criterion emphasizes the concept of compression of the thecal sac and nerve roots. The term stenosis indicates a disproportion between the caliber of the container and the volume of the content. If the content is solid or semifluid, as in the vertebral canal, the dimensional disproportion results in compression of the content by the walls of the container. However, the disproportion is not strictly related to the anteroposterior dimensions of the vertebral canal, as believed by Verbiest.2 Severe compression of the neural structures may occur even if the sagittal dimensions of the canal are within normal limits. On the other hand, a midsagittal diameter of 10 mm or less does not necessarily lead to compression of the cauda equina.3 This is probably due to the fact that the neural structures develop in harmony with the dimensions of the canal. When this does not occur, the reserve space available for the thecal sac and/or the caudal nerve roots is variably reduced and, therefore, acquired constrictive conditions of even minor degree are sufficient to cause stenosis. If the narrowing is not severe enough to cause compression of the neural structures, the spinal canal is to be considered narrow but not stenotic. Therefore, a diagnosis of stenosis cannot be made solely on the basis of measurements of the size of the vertebral canal or the area of the thecal sac in the axial sections. The radiologic diagnosis of stenosis should be predicated upon the demonstration of compression of the neural structures, whether clinically symptomatic or asymptomatic, by an abnormally narrow osteoligamentous spinal canal (Fig. 87.1).

CLASSIFICATION

Site of constriction

Lumbar spinal stenosis can be distinguished, based on the site of constriction, as stenosis of the spinal canal or central stenosis, isolated stenosis of the nerve root canal or lateral stenosis, and stenosis of the intervertebral foramen (Table 87.1).

Table 87.1 Classification of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

| CENTRAL STENOSIS | |

| Primary | |

| Congenital | |

| Developmental | |

| Achondroplastic | |

| Constitutional | |

| Secondary | |

| Degenerative | |

| Simple | |

| With degenerative spondylolisthesis or scoliosis | |

| Late sequelae of fractures or infections | |

| Paget’s disease | |

| Combined | |

| Association of primary and secondary forms at the same vertebral level | |

| ISOLATED LATERAL STENOSIS | |

| Primary | |

| Secondary | |

| Combined | |

| STENOSIS OF THE INTERVERTEBRAL FORAMEN | |

| Primary | |

| Secondary | |

| Combined | |

In stenosis of the spinal canal, the entire area of the canal, as viewed on the axial plane, is usually constricted (Fig. 87.2). In other words, both the central portion of the canal and the lateral parts, occupied by the emerging nerve roots, are constricted. Therefore, the expression stenosis of the spinal canal is more correct than that of central stenosis, which would indicate constriction only of the central area. However, the authors will use the latter term because it has become the one commonly adopted.

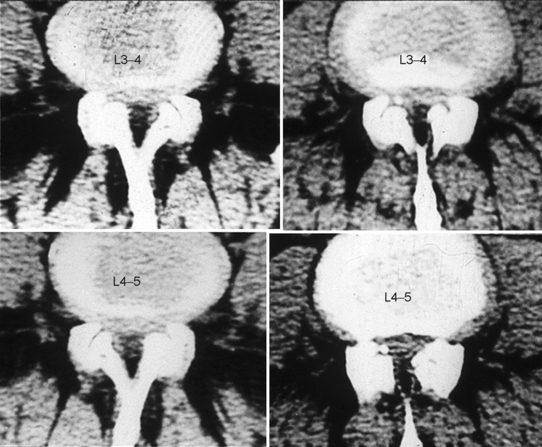

The nerve root canal or radicular canal corresponds to the lateral portion of the spinal canal (Fig. 87.3). This canal, which is more of an anatomical concept than a true canal, is the semitubular structure in which the nerve root, exiting from the thecal sac, travels before entering the intervertebral foramen. As for the central form, in the last decade, the term lateral stenosis has become the most widely used for this type of stenosis.

Type of stenosis

Three forms of stenosis can be identified: primary, secondary and combined (see Table 87.1).

Primary forms

Central stenosis

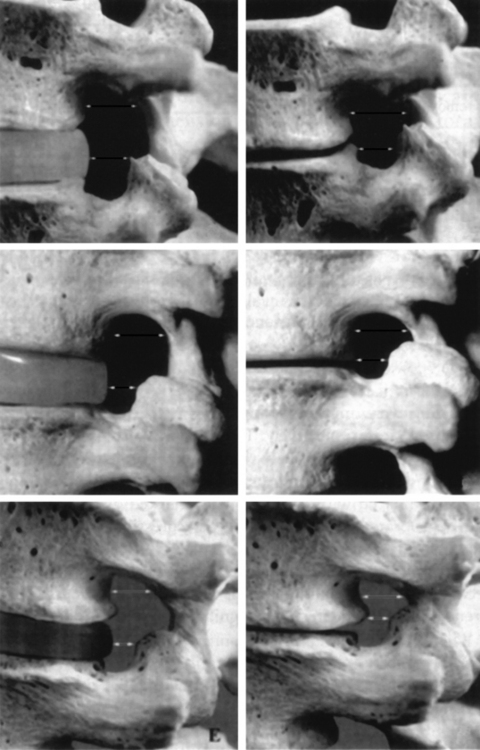

Developmental stenosis includes achondroplastic and constitutional forms. In the former, the midsagittal and/or interpedicular diameters of the spinal canal are abnormally short and the nerve root canals are severe narrowed due to abnormal shortness of the pedicles. In constitutional stenosis the cause of the defective vertebral development is unknown. In the authors’ experience, two types of constitutional abnormality may be identified: (1) a short midsagittal diameter of the spinal canal, and (2) an exceedingly sagittal orientation and/or shortness of the pedicles (Fig. 87.4). In the latter type, the spinal canal is abnormally narrow, mainly or only, in the inter-articular diameter.

Secondary forms

Central stenosis

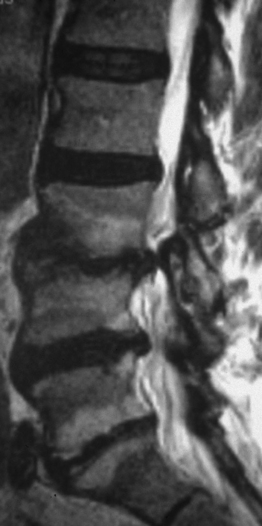

If the sagittal dimensions of the spinal canal are normal, or at the lower limits, and compression of the caudal nerve roots is the result of one or more acquired conditions, such as spondylotic changes of the facet joints, abnormal thickening of the ligamenta flava, and bulging of the intervertebral discs, then this form is defined as simple degenerative stenosis (Fig. 87.6).

Very often, however, degenerative spondylolisthesis of the cranial vertebra of the motion segment is also present at one or, occasionally, two or more levels (Fig. 87.7). Degenerative spondylolisthesis is consistently responsible for narrowing of the spinal canal, but may not cause lateral or central stenosis. This is because the presence, type, and severity of stenosis is related to several factors, such as the constitutional dimensions of the spinal canal, the orientation (more or less sagittal), and the severity of degenerative changes of the facet joints, and the amount of vertebral slipping, which may in some cases play a minor role. For example, a grade I spondylolisthesis in a patient with a constitutionally large spinal canal produces no significant narrowing of the canal, would be categorized as no stenosis. In contrast, the same or even lesser grade of spondylolisthesis in a patient with a primarily narrow canal can be associated with clinically significant stenosis. The type of stenosis, that is whether stenosis is central or lateral, depends on the orientation of the articular processes and the length of the pedicles. Usually, stenosis initially presents as lateral and then central in later stages. Instability, that is hypermobility on flexion–extension radiographs, is one of the main characteristics of degenerative spondylolisthesis. However, in many cases there is no appreciable hypermobility of the slipped vertebra. The authors consider the latter condition as a potential instability, which can become unstable as a result of surgery. Such a scenario may arise following removal of a large part of one or both facet joints, unilateral or bilateral discectomy, or when destabilizing factors unable to stabilize a normal vertebra intervene, such as disc degeneration or severe degenerative changes of the facet joints. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, the intervertebral disc often bulges into the intervertebral foramen to cause stenosis. However, true stenosis of the foramen is rarely present as the foramen becomes larger in the sagittal dimensions in the presence of slipping of the cranial vertebra.

Lateral stenosis

Most often, this form of stenosis is degenerative in nature. Usually, degenerative stenosis involves only the lateral portions of the spinal canal in the initial stages and become central in more advanced stages when spondylotic changes becomes more severe. This is particularly true for degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Lateral stenosis can occur due to a cyst of the facet joint when it compress the emerging root in the nerve root canal (Fig. 87.8).

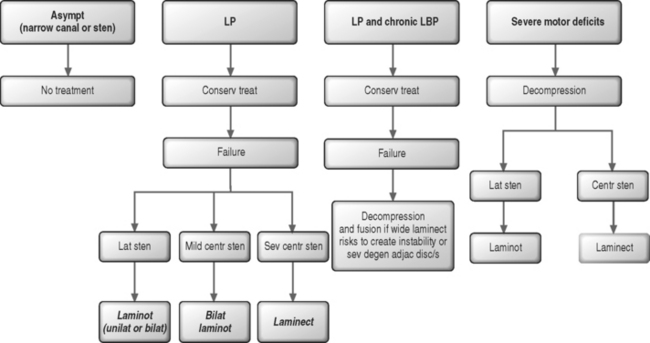

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

In patients with leg symptoms, surgery is indicated when comprehensive conservative management as described in other chapters of this book have been carried out for 4–6 months without resulting in significant improvement (Fig. 87.9). The exception to this recommendation is for patients with a severe motor and/or sensory deficit consistent with cauda equina syndrome, who require emergent neural decompression.

Usually, there is no need for spinal fusion. Arthrodesis may be indicated when there is a concern that wide surgical decompression could result in postoperative instability. Additionally, fusion may be required for the patient that is experiencing simultaneous radicular pain from spinal stenosis and axial back pain due to internal disc disruption syndrome (see Fig. 87.9).

Advanced age

Surgical decompression may offer significant relief of symptoms also to patients older than 70 years.5–8 In the authors’ experience, there is no significant difference in the results of surgery between the patients in early senile age and those aged 80–90 years old, provided the stenosis is severe and the patient’s general health is satisfactory.

Comorbidity

In one study,7 a high rate of comorbid illnesses was found to be inversely related to the rate of satisfactory results after surgery. Another study9 compared the long-term results of surgery in 24 diabetic and 22 nondiabetic patients. In the diabetic group there was a 41% rate of satisfactory results, compared with 90% in the nondiabetic group. Different results, however, were observed in a similar study,10 in which the outcome was satisfactory in 72% of the diabetic and 80% of the nondiabetic patients. Neither the duration of the diabetes before surgery nor its type correlated with the outcome. A mistaken preoperative diagnosis was the main cause of failure in diabetic patients. In many of the failures, diabetic neuropathy or angiopathy had elicited symptoms that had been confused with pseudoclaudication.

Previous surgery

Surgery for spinal stenosis tends to give less satisfactory results in patients who had previously undergone decompressive procedures in the lumbar spine.7,11–14 This is particularly true when stenosis is at the same level or levels at which the previous surgery for disc herniation or stenosis had been performed.15

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Definition of terms

Decompression of the lumbar spinal canal can be carried out by total laminectomy, also defined as bilateral or complete laminectomy (Fig. 87.10). More focal decompression can be accomplished with a laminotomy, also called keyhole laminotomy, hemilaminectomy, or partial hemilaminectomy. Laminotomy consists in the removal of the caudal portion of the proximal lamina, the cranial portion of the distal lamina and a varying portion of the articular processes, together with a part of, or the entire, ligamentum flavum on the side of surgery. Laminotomy can be performed at a single level on one side or both sides (Fig. 87.11). Less frequently it is performed at multiple levels (Fig. 87.12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree