Surgical Considerations with Failed Posterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery

Michael K. Gilbart MD

Champ L. Baker III MD

Christopher D. Harner MD

History of Technique

Knowledge of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) has been slowly improving due to studies on its anatomy and biomechanics. Controversy exists concerning the most appropriate treatment, especially in cases of isolated PCL injury. For those patients who have had a PCL reconstruction that unfortunately progresses to failure, there is a paucity of literature published on the potential mechanisms of failure and available treatment options. A PCL reconstruction failure may consist of a combination of subjective factors of pain, instability, or stiffness as well as objective findings of laxity, progressive degenerative changes, or loss of motion. Residual laxity generally occurs in the posterior and posterolateral directions, and degenerative changes usually occur in the medial compartment.1,2

The causes of failure of the PCL reconstruction should be identified. Failures may be classified as primary or secondary. Primary failures are generally caused by inadequate surgical technique, such as failure to recognize and treat combined instabilities, improper tunnel placement, inadequate graft tensioning or fixation, or incomplete initial management of meniscal and articular pathology. Secondary failures may be caused by inadequate biology and graft healing, overly aggressive rehabilitation protocols, repetitive trauma, or patient noncompliance. Noyes and Barber-Weinstein3 recently reported on multiple causes of failure following PCL reconstruction in 41 patients and found the presence of untreated posterolateral corner injury in 41% of patients, improper tunnel placement in 39%, and untreated varus malalignment in 27% of patients.

Revision PCL reconstructions should be adequately planned prior to surgery. The operative considerations include graft selection, the use of one- or two-bundle techniques as well as the option of either a transtibial or tibial inlay technique. Other considerations include the location of femoral tunnels, graft tensioning and fixation, the treatment of combined instabilities, treatment of pre-existing meniscal or articular pathology, and the necessity of performing a high tibial valgus osteotomy (HTO).

Principles of Management

The clinical examination is extremely important in the evaluation and creation of a management plan for failed PCL reconstruction. Patient evaluation should consist of a thorough preoperative history and physical examination, including a review of all patient records and operative reports. It should be determined whether the main subjective patient complaint is one of pain or instability.

The physical examination should help the clinician evaluate for potential causes of failure of the PCL reconstruction.2 An evaluation of knee range of motion as well as an evaluation of primary and secondary restraints should be performed. Specifically, does the objective evaluation demonstrate a problem with increased laxity or decreased range of motion?

The knee should be evaluated for the presence of a positive posterior drawer, quadriceps active test, or Godfrey test (flexion of hip and knee to 90 degrees, a positive test is posterior displacement of tibia).2 The knee should be evaluated for fixed posterior tibial subluxation. It is critical to recognize any associated, untreated combined instability, as studies have shown that leaving such instabilities untreated will cause increased in situ forces on the PCL and increased failure rates of PCL reconstructions.4,5,6 It is generally recognized that if there is excessive posterior translation of the tibia on examination (grade 3, or >10 mm), one must rule

out an associated posterolateral corner injury.7 This can be assessed using the tibial dial test at 30 degrees and 90 degrees of knee flexion. Increased tibial external rotation at 30 degrees is consistent with an isolated posterolateral corner injury, while increased external rotation at 30 degrees and 90 degrees is indicative of a combined PCL/posterolateral corner injury.2

out an associated posterolateral corner injury.7 This can be assessed using the tibial dial test at 30 degrees and 90 degrees of knee flexion. Increased tibial external rotation at 30 degrees is consistent with an isolated posterolateral corner injury, while increased external rotation at 30 degrees and 90 degrees is indicative of a combined PCL/posterolateral corner injury.2

Standing limb alignment should be assessed, including the recognition of any associated bony deformity. Gait should be evaluated for the presence of a varus thrust or excessive recurvatum. One may need to first address this varus alignment, as the presence of a varus deformity stresses the posterolateral structures excessively, leading to failure of the ligament reconstruction. In this situation an anteromedial opening wedge (biplanar) osteotomy is indicated for correction of the varus deformity and also to increase the posterior tibial slope.8 An increase in the tibial slope has been found to cause an anterior shift in the resting position of the tibia, and this is beneficial in reducing the posterior tibial sag in PCL deficient knees.9 In general, the biplanar osteotomy is indicated for patients with medial joint line pain with activities of daily living, varus malalignment of the mechanical axis of the knee, and residual PCL laxity. If there is no associated posterolateral corner injury, one should re-evaluate the patient after allowing an adequate amount of time for the biplanar osteotomy to heal, as some of these patients may not require definitive PCL revision.

It is important to perform a thorough evaluation of the neurovascular status of the affected extremity with special attention to the presence of any pre-existing injury to the popliteal vessels or peroneal nerve. An arteriogram is recommended and should be performed preoperatively for any patient with concerns about a potential preoperative vascular injury. We strongly recommended that when there is any doubt about the vascular status of the extremity, one should obtain a preoperative arteriogram.

Fig. 47-1. Stress radiograph illustrates posterior subluxation, but may also be helpful to determine presence of fixed posterior subluxation. |

One should make note of any prior skin incisions, as these are important to consider during the planning of any future surgery.

A routine knee series including PA flexion weight bearing (45 degrees), lateral radiographs, Merchant views, and a long cassette should be obtained. Stress radiographs may be useful, especially for those patients with suspected fixed subluxation (Fig. 47-1). Radiographs allow evaluation of tunnel position and size, position of hardware, degree of subluxation, and associated pathology. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful for detecting any meniscal pathology or articular cartilage abnormalities.

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for a revision PCL reconstruction include a patient with a previous failed PCL reconstruction and continued symptoms of pain and instability. A thorough preoperative assessment for associated instabilities should be undertaken, and these should be addressed along with the PCL revision reconstruction. Relative contraindications for surgery include a severe preoperative loss of range of motion and a fixed posterior drawer (one that cannot be reduced manually).8 Absolute contraindications for PCL reconstruction include advanced osteoarthritis of the knee or active infection.

The surgeon should take into consideration the reliability and compliance of the patient prior to revising a PCL reconstruction. The surgeon must adequately counsel each patient through the informed consent process and should offer a realistic perspective of the expected outcome, the complexity of the surgery, and the associated risks. Patients should be aware that the results of revision and salvage PCL reconstructions may not be as good as a primary PCL reconstruction.

Surgical Techniques

The technique of reconstruction required is dependent upon the etiology of the PCL failure and the patients’ symptoms. Surgery may be performed as a one- or two-stage procedure. If the previous tunnels show excessive widening and resorption, the fixation hardware should be removed and the tunnels bone grafted and allowed adequate time to heal and incorporate (usually 6 months).

Biplanar Opening Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy

Preoperative templating using standing long cassette radiographs is essential. The planned osteotomy should be

drawn, and an estimate of the proximal tibial width and necessary plate size should be made by taking radiographic magnification into account. The width of the opening wedge osteotomy on the tibia is determined by the degree of desired correction.

drawn, and an estimate of the proximal tibial width and necessary plate size should be made by taking radiographic magnification into account. The width of the opening wedge osteotomy on the tibia is determined by the degree of desired correction.

The patient is placed supine on the operating table. The preferred anesthesia is a combination of regional femoral and/or sciatic nerve block with a laryngeal mask anesthetic. The landmarks on the knee must be drawn, including the inferior pole of the patella, tibial tubercle, joint line, fibular head, a Gerdy tubercle, and the peroneal nerve. We use a Bovie cord and C-arm to mark a straight line from the center of the hip to the center of the ankle, noting its position as it crosses the knee joint (medial to the tibial spine in a varus knee).

An incision is made midway between the medial border of the tibial tubercle and the posterior border of the tibia. The incision begins 1.0 cm inferior to the joint line and extends approximately 5 cm distally. Exposure is made down to the superficial fibers of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), and subcutaneous flaps are created to allow exposure of the patellar tendon and the tibial tubercle. The patellar tendon is then retracted laterally. An incision is then made in the sartorius fascia just superior to the gracilis tendon, and a subperiosteal dissection is completed superiorly to release the superficial fibers of the MCL off of bone. Care must be taken to stop the subperiosteal dissection just distal to the joint line, to preserve the deep fibers of the MCL.

A tibial guide wire is placed from an anteromedial to a posterolateral direction angled 15 degrees cephalad along the proposed osteotomy, and its position is confirmed with the C-arm. The line of the osteotomy should be just superior to the tibial tubercle. The width of the proximal tibia should then be confirmed using a free K-wire to confirm that the actual tibial width at the osteotomy site matches the templated tibial width on preoperative radiographs. This allows for the surgeon to confirm an adequate tibial osteotomy correction will be performed. A 1-inch osteotome is recommended to start the osteotomy, using the K-wire as a directional guide. Once the osteotomy plane is initiated, the K-wire may be removed and the osteotomy completed using an oscillating saw or osteotome, taking care to protect a posterolateral hinge of cortical bone for stability. To safely complete the osteotomy across the posterior tibial cortex and to protect the neurovascular structures, the surgeon must angle the osteotome to avoid excessive perforation of the posterior cortex.

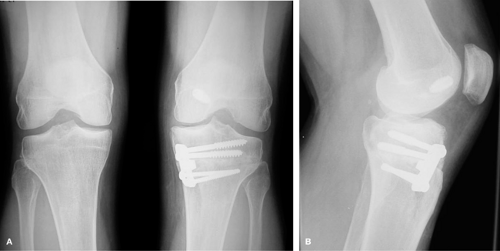

Fig. 47-2. Postoperative (A) AP and (B) lateral radiographs after biplanar osteotomy and plate fixation. |

The Arthrex (Arthrex Inc, Naples, FL) opening wedge osteotomy system is used, and the wedge device is inserted into the osteotomy site to create the desired angle of correction. If added distraction is required, a laminar spreader may be used in the osteotomy, but it is best placed anteriorly under the thick bone of the tibial tubercle to prevent damage to the metaphyseal bone. The appropriate plate is then selected and placed in the anteromedial aspect of the osteotomy for a biplanar effect. The alignment of the leg is again checked using the Bovie cord and C-arm from the center of the hip to the center of the ankle in order to ensure that it crosses the knee joint lateral to the tibial spine, indicating an adequate correction. The plate is then fixed proximally with two cancellous screws directed parallel to the articular surface. Distally the plate is secured with 4.5 mm self-tapping screws with purchase into the lateral cortex (Fig. 47-2). Wedge cuts of femoral head allograft are fashioned to bone graft the osteotomy site. The superficial MCL is sutured down to the medial tibial

metaphysis using suture anchors. Wound closure is achieved using a no. 0 absorbable suture, followed by no. 2-0 absorbable interrupted sutures. Skin is closed using skin staples.

metaphysis using suture anchors. Wound closure is achieved using a no. 0 absorbable suture, followed by no. 2-0 absorbable interrupted sutures. Skin is closed using skin staples.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree