CHAPTER 60 Surgery for Cervical Radicular Pain

INTRODUCTION

Historical notes

The first recognized case of cervical radiculitis caused by herniation of the nucleus pulposus was operated on by Professor Angelo Chiasserini, one of the founders of Italian neurosurgery, in January 1937. Previously, cases of cervical ‘chondromas’ had been described but the specific pathophysiology of discogenic cervical radiculitis was not recognized.1

The advent of the Smith—Robinson technique, later popularized with methodology by Cloward, led to a dramatic shift of the direction of treatment for cervical radiculopathy from posterior to anterior. Indeed, Angevine et al. reported that the United States national rates for cervical discectomy with and without anterior fusion had changed dramatically during the 1990s with a marked increase in the inclusion of a fusion procedure.2 There was a significant geographic distribution in the rate of fusion for cervical disc disease, with the South having the highest fusion rate. Although the rate of surgery for cervical disc disease did not increase significantly during the 1990s, the rates of fusion procedures did rise significantly.

Contraindications

There are definite and, in the author’s opinion, controversial contraindications to surgery.

Workmen’s compensation

There are now ample data which indicate that patients who believe that their radiculopathy is the result of a work-related accident, for which they believe they should be compensated, do significantly worse than patients who are not compensated for their cervical radiculopathy. The reasons for this are complex and sometimes difficult to understand. In many instances there may be a conscious effort on the part of a patient to prolong the symptoms while getting reimbursement without working. In other instances, however, it seems that the mere involvement in the compensation system is sufficient to cause a patient to believe that he or she has been ‘injured’ and should be paid while recovering from these injuries. Assessment of such patients is complex. Many do not appear to be pure malingerers. Others indicate that they are an intensely interested in returning to work yet all treatment modalities, including surgery, fail. Still others will apparently recover from their cervical radicular surgery, which apparently proceeded with good results, yet still be unable to return to work although they can function in almost any other environment. The conscientious surgeon, who analyzes the outcome of the surgery, must consider a patient who continues to complain of pain and cannot work as a surgical failure. Too often, a surgeon will assume that his obligation has been completed when he performs an effective surgery with good clinical and radiographic indications. In patients not encumbered with psychosocial factors, one can generally expect good results in 95% of cases. If surgery is performed, however, and the patient cannot return to work, and is still receiving compensation payments, the surgeon must wonder whether he or she has really performed any useful service, particularly if relief of pain and return to normal activity are the personal outcome requirements. There is overwhelming evidence that patients covered by workmen’s compensation claims did generally poorer than individuals who believe that their cervical radiculopathy is the result of a natural process. The references for this are extensive, and many of them will include patients with lumbar radiculopathy whose response, when under workmen’s compensation, is similarly affected negatively.

TECHNIQUE

Posterior cervical nerve root decompression

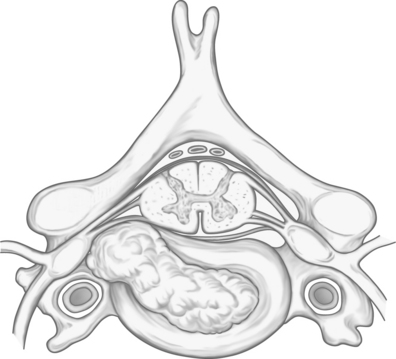

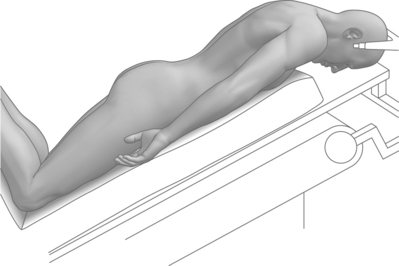

In the author’s opinion, this highly effective operation is dramatically underused in the United States for reasons which remain mysterious. The posterior operation provides nerve root decompression, long-term relief of radicular symptoms, without the necessity to fuse the cervical spine. The complication rate is substantially less than anterior discectomy. The procedure, however, cannot be used for midline cervical disc herniations where a spinal cord compression is the principal pathology (Figs 60.1–60.8).

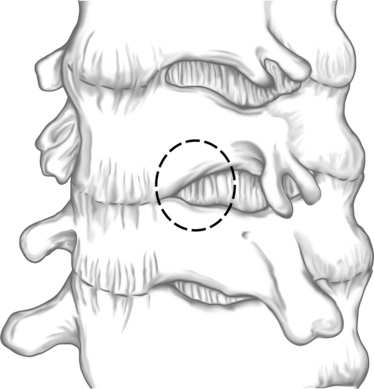

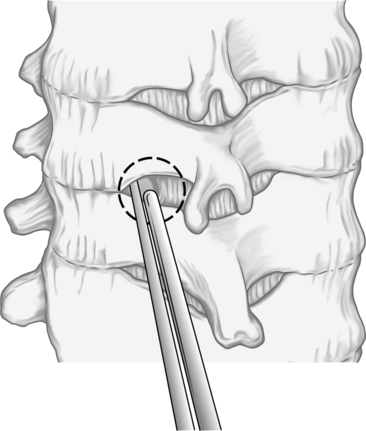

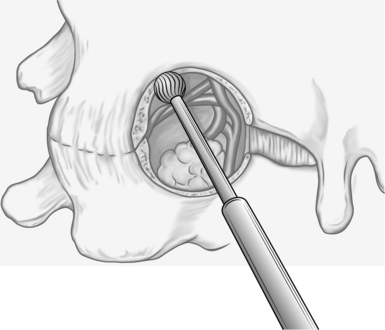

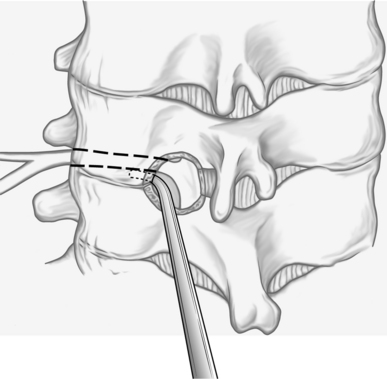

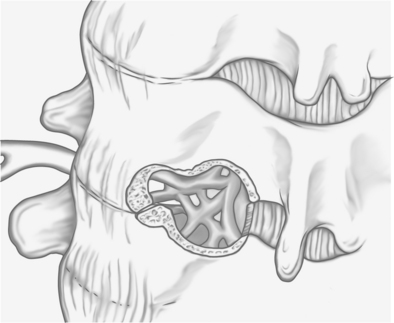

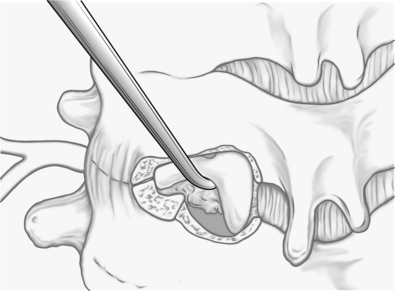

For a single-level nerve root decompression, an incision of approximately 2.5 cm is made over the affected spinous processes. The level is confirmed radiographically, intraoperatively. The cervical muscles on one side are dissected free from the lamina and held in place with the retractor. Under microscopic control, the inferior margin of the lamina of the superior vertebra and the superior margin of the lamina of the inferior vertebra are removed with drills or rongeurs so that the top of a ‘keyhole’ is visualized. The bottom of the keyhole, of course, is the bony structures over the affected nerve root. Under microsurgical control, the dorsal portion of the intervertebral foramen through which the affected nerve root passes is drilled down to a thin eggshell which is then removed with a small curette. Alternatively, a small Kerrison rongeur can be used to complete the foraminotomy without compressing the underlying nerve root. At the end of this procedure, one should easily be able to pass an instrument through the foramen and determine that there is no pressure on the nerve root. This dissection can be carried out pedicle-to-pedicle and generally involves only the medial half of the facet joint. As such, instability has not been demonstrated when the procedure is performed unilaterally. In young patients with an acute history, and in preoperative studies, where one suspects a free disc fragment, it is possible to remove the extruded disc material to obtain even more immediate relief. Generally, it is necessary to coagulate the overlying venous cuff in order to expose the disc herniation. When the herniation is incised there can be a spontaneous extrusion of the disc material, and in the author’s experience, this generally portends an excellent result with immediate relief of arm pain. When the pathology is ‘hard,’ that is secondary to an osteophyte, a wide decompression as described above is sufficient to relieve the patient’s symptoms permanently. It is not necessary to attempt to flatten, remove, or otherwise manipulate the anterior osteophytes since the pathology is apparently a ‘sandwich’ effect and removing one portion of the sandwich on either side adequately releases the pressure of the foraminal contents. As discussed elsewhere in this book, this procedure can be performed using even more minimally invasive techniques. Narrow retractors which access the foramen by splitting the paraspinous muscles through an even smaller incision (1.5 cm) have facilitated a less painful recovery. There are several advantages to this approach over the anterior operation specifically for cervical radiculopathy. First of all, several roots can be examined, and it is frequent that multiple roots are involved, without fusing multiple spine segments and thereby applying undue stress on the remaining non-fused motion segments. Secondly, the mechanics of the spine are not altered by surgical immobilization. Furthermore, the risk to the esophagus, larynx, and adjacent structures is eliminated because the approach will only involve the paracervical musculature before the level of the pathology is reached.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree