Suprascapular Nerve Decompression

Orr Limpisvasti MD

Ronald E. Glousman MD

History of the Technique

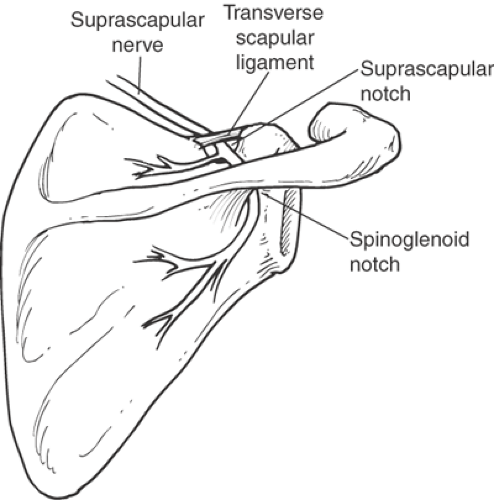

Thomas first described suprascapular nerve palsy in the French literature in 1936.1 Since that description, there have been many reports in the English literature describing the pathoanatomy, clinical findings, and treatment of suprascapular neuropathy.2,3,4,5 The suprascapular nerve is primarily a motor nerve that originates from the fifth, sixth, and occasionally fourth cervical nerve root. Although there are rarely cutaneous sensory fibers, branches of the nerve receive afferent sensory input from the glenohumeral joint, acromioclavicular joint, and the coracohumeral ligament. Suprascapular neuropathy can result from nerve traction, extrinsic compression, direct trauma, or a primary neuropathy. The suprascapular nerve is particularly prone to injury as it crosses through the suprascapular notch to supply the supraspinatus muscle and then again at the spinoglenoid notch as it travels into the infraspinatus fossa.

Traction injury at the suprascapular notch and spinoglenoid notch is a common etiology of neuropathy in overhead athletes. Repetitive stretching of the nerve can occur as it courses through a confined space, leading to direct nerve injury or injury to the vascular supply of the nerve. This mechanism can be exacerbated by extreme positions of abduction and retraction found in overhead sports (volleyball, baseball, tennis). Extrinsic compression of the suprascapular nerve can also occur at the spinoglenoid notch secondary to ganglion cysts. These ganglion cysts are often associated with glenohumeral pathology such as labral tears.

The natural history of suprascapular neuropathy is not well documented, but in the athletic population, there can be a significant number of asymptomatic athletes with clinically evident suprascapular neuropathy.6,7,8 One study in volleyball players suggests that athletes can remain asymptomatic despite findings of atrophy and weakness on clinical examination.8 Symptomatic suprascapular neuropathy without evidence of a compressive lesion should be initially treated with nonoperative treatment. Martin et al.2 reported that 80% of their patients treated nonoperatively improved without the need for nerve decompression. Nonoperative treatment in their study included strengthening of the deltoid, rotator cuff, and periscapular muscles for a minimum of 6 months while avoiding exacerbating activities. Other conservative measures include anti-inflammatory medications and the selective use of corticosteroid injections. Patients who have symptoms refractory to conservative management may be candidates for suprascapular nerve decompression.

Many different techniques have been described to decompress the nerve at the suprascapular notch. An anterior approach starting medial to the coracoid has been described to reach the suprascapular notch.9 The increased risk of iatrogenic neurovascular injury with this dissection has led most authors to advocate either a superior or posterior approach to access the suprascapular nerve. The superior approach is a trapezius-splitting approach advocated by Vastamaki and Goransson.10 The trapezius is split in line with its fibers directly above the suprascapular notch, and the supraspinatus muscle is retracted posteriorly to visualize the notch. The topographical landmarks for the superior approach have been defined in a recent cadaveric study.11 The posterior approach, advocated by Post and Grinblat,3 is the one most commonly used in our practice to visualize the suprascapular notch. This approach involves elevation of the trapezius from the scapular spine. For open decompression of the suprascapular nerve at the spinoglenoid notch, a posterior approach through the deltoid is generally recommended.4 This approach can either utilize a split of the deltoid in line with its fibers or a release of the posterior deltoid from the spine. Subsequent inferior retraction of the infraspinatus muscle exposes the spinoglenoid notch. Although the surgical

approaches described may vary, the actual decompression of the nerve generally includes the release of the transverse scapular ligament, spinoglenoid ligament, or both ligaments. Some authors have also advocated osseous decompression of a stenotic notch.

approaches described may vary, the actual decompression of the nerve generally includes the release of the transverse scapular ligament, spinoglenoid ligament, or both ligaments. Some authors have also advocated osseous decompression of a stenotic notch.

Indications and Contraindications

The first step toward determining the appropriate treatment for suprascapular nerve entrapment is confirming diagnosis. The subjective complaints of the patient can vary significantly, especially in overhead athletes. Many asymptomatic overhead athletes have well-documented suprascapular neuropathy on clinical examination. Symptomatic patients frequently describe a poorly localized discomfort or ache over the posterior and lateral aspects of the shoulder. Whether this pain is from injury to the sensory branches of the posterior glenohumeral joint or secondary to rotator cuff deficiency is unknown. Pathology at the suprascapular notch is generally more symptomatic with regard to weakness and pain than pathology at the spinoglenoid notch. By the time the suprascapular nerve has reached the spinoglenoid notch, it has already given off its motor branches to the supraspinatus and received afferent fibers from the posterior joint capsule.

Objective findings vary with the progression of the disease and the location of nerve entrapment. The location of suprascapular nerve injury as it travels through the suprascapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch determines the location of muscle atrophy (Fig. 21-1). Nerve pathology at the spinoglenoid notch will present with atrophy isolated to the infraspinatus muscle. Although wasting of the infraspinatus may be less symptomatic, it is generally more visible than atrophy of the supraspinatus due to the overlying trapezius muscle. Weakness of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus can often be clinically detected even though weakness may not be a primary subjective complaint of the athlete. Pain in the posterior shoulder can sometimes be reproduced with cross-body adduction and internal rotation; however, this should be differentiated from pathology at the acromioclavicular joint. There can also be point tenderness to palpation over the suprascapular notch or posterior joint line.

Fig. 21-1. The suprascapular nerve passes beneath the transverse scapular ligament in the suprascapular notch and around the base of the scapular spine through spinoglenoid notch. |

Concomitant and precipitating pathology in the overhead athlete can include glenohumeral instability, scapular dyskinesis, and labral pathology. Posterior and superior labral pathology has been associated with spinoglenoid notch cysts and suprascapular nerve compression. Careful examination of glenohumeral stability as well as scapulothoracic mechanics is warranted when evaluating a shoulder with suprascapular neuropathy.

The differential diagnosis of suprascapular nerve palsy includes primary mononeuropathy, cervical radiculopathy, brachial plexitis (Parsonage-Turner syndrome), quadrilateral space syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, rotator cuff disease and neoplasm, or other compressive mass. Clinically, we have found that proximal neuropathies such as cervical radiculitis and brachial plexopathy are generally more common etiologies confounding diagnosis of suprascapular nerve entrapment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree