Strategies for Handling the Flexible Fixed Swan-Neck Deformity

Kenneth Robert Means Jr

INTRODUCTION

Swan-neck deformity of the fingers is defined as proximal interphalangeal (PIP) hyperextension and distal interphalangeal (DIP) flexion. Concomitant metacarpophalangeal (MCP) flexion deformity is possible though it is not a requisite feature. Fortunately, hand surgeons today do not frequently encounter debilitating swan-neck deformities in patients. This is especially true due to the recent advent of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) that have revolutionized the care of many rheumatologic conditions and prevented many crippling extremity deformities, including swan-neck posturing of the digits. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the classic rheumatologic condition that causes flexible swan-neck deformities, but other conditions can lead to this problem as well (Fig. 12-1). Unfortunately, a lack of familiarity with swan-neck deformities on the surgeon’s part may lead to uncertainty when treating patients with this potentially complex problem. This is likely particularly true for younger surgeons who may not have as much experience, due to the use of DMARDs, with the many possible presentations, pathologies, and treatment options for these deformities. Part of the challenge of treating patients with swan-neck deformity is that, unlike boutonniere deformity that by definition originates at the PIP joint, swan-neck deformity can originate at the wrist, MCP, PIP, or DIP joints, and often, there is pathology at more than one joint contributing to the deformity. One of the first things surgeons should try to determine when treating a patient with a swan-neck deformity is the underlying pathologic and anatomic cause of the deformity; knowing this will help guide treatment. Surgeons typically start correction of swanneck deformity at the most proximal involved joint and progress distally either at the same surgical setting or in stages.

Today, hand care professionals are most likely to see patients present with swan-neck deformities as the result of trauma, such as a mallet finger injury or PIP joint dislocation. Swan-neck posturing after these types of injuries is typically not as severe as that with rheumatologic conditions. These patients may have clinically insignificant swan-neck posturing in which they are still able to actively initiate PIP joint flexion, and the deformity may be more of a cosmetic concern. In these cases, the main focus is on preventing worsening of the deformity, which could then lead to significant

functional limitation. This entails the use of a PIP dorsal block or figure-of-eight splint to prevent hyperextension but still allow flexion. Intrinsic stretches are also helpful if the patient demonstrates significant intrinsic tendon tightness. The main functional limitation for patients with clinically significant flexible or fixed swan-neck deformity is their inability to flex the PIP joint. For patients with flexible deformity, this means that they have to use their other hand or place the dorsum of the affected digit against something in order to initiate active PIP flexion. For patients with fixed deformity, the PIP joint is by definition in a hyperextended and contracted position and unable to flex even passively beyond this point. Other causes of clinically significant swan-neck deformity include more severe trauma such as hand crush injuries with severe intrinsic contractures, burns with dorsal skin and soft-tissue contractures, neuromuscular conditions with hand intrinsic muscle spasticity and eventual joint contracture, and patients at varying places along the spectrum of generalized hyperextensibility. Evaluation and treatment of these more rare and specialized causes of swan-neck deformity are beyond the scope of this chapter.

functional limitation. This entails the use of a PIP dorsal block or figure-of-eight splint to prevent hyperextension but still allow flexion. Intrinsic stretches are also helpful if the patient demonstrates significant intrinsic tendon tightness. The main functional limitation for patients with clinically significant flexible or fixed swan-neck deformity is their inability to flex the PIP joint. For patients with flexible deformity, this means that they have to use their other hand or place the dorsum of the affected digit against something in order to initiate active PIP flexion. For patients with fixed deformity, the PIP joint is by definition in a hyperextended and contracted position and unable to flex even passively beyond this point. Other causes of clinically significant swan-neck deformity include more severe trauma such as hand crush injuries with severe intrinsic contractures, burns with dorsal skin and soft-tissue contractures, neuromuscular conditions with hand intrinsic muscle spasticity and eventual joint contracture, and patients at varying places along the spectrum of generalized hyperextensibility. Evaluation and treatment of these more rare and specialized causes of swan-neck deformity are beyond the scope of this chapter.

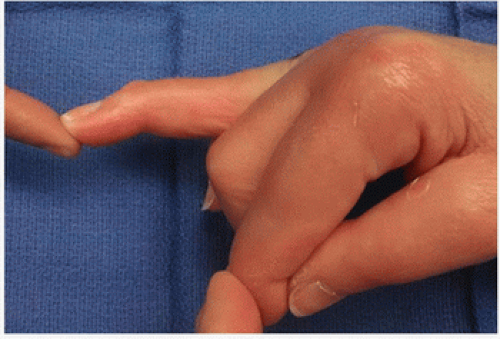

FIGURE 12-1 Patient with SLE and several fingers with tendencies toward swan-neck deformity, most pronounced in the small finger where the patient is unable to actively initiate PIP flexion. |

There have not been many recent changes in the nonoperative and operative management of swan-neck deformity. Authors have reported recent results with different techniques as well as modifications to some of the techniques (1). In this chapter, I present what I believe to be the most effective surgical techniques for the most commonly encountered swan-neck pathologies. I have also sought the collective experience and wisdom from all of the surgeons at our hand center and will acknowledge many of their tips throughout the chapter to further this cause. I am of course also indebted to the authors of the excellent chapter in the previous edition of this text and draw on their observations and recommendations here as well (2).

INDICATIONS

Patients with functional issues due to the swan-neck deformity for which splints are ineffective or impractical; in most cases, surgical intervention will not increase the overall range of motion for the finger but will make the range of motion take place in a more functional arc.

Patients with progressive deformity that may lead to functional deficits; this involves more of a preventative approach, such as treating an acute or chronic mallet injury in order to prevent further progression of the swan-neck deformity.

Patients with flexible deformities are, by definition, fully passively correctable; for these patients, soft-tissue reconstruction options are indicated.

Patients with fixed deformities are indicated for joint release followed by soft-tissue reconstruction only if the articular surfaces are in acceptable condition. Arthrodesis or arthroplasty is indicated when the articular surfaces are not in acceptable condition.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Patients who cannot reliably follow postoperative instructions including a therapy protocol

Patients with severe medical comorbidities or infection that preclude surgical intervention

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The most important part of the preoperative preparation for patients with flexible swan-neck deformities is to determine the primary, and any secondary, cause(s) of the deformity. This is typically achieved through a good history and physical exam. During the history, the surgeon should determine the timing and sequence of development of the deformity, any discrete pain locations, the presence of significant mechanical issues such as joint(s) locking or being unstable in certain positions, history of trauma or other surgical procedures, and how the deformity is impacting the patient’s life. During the physical exam, the surgeon is looking for any joints that are synovitic from the wrist to the DIP joint, the resting and active posture of the digit including the joints that are most significantly contributing to the deformity, the condition of the skin and soft-tissue envelope for the finger, tenderness at any joints, the suppleness of any deformities, and any flexor or extensor mechanism abnormalities including assessment of extrinsic extensor or flexor tightness and utilizing the Bunnell test to reveal any intrinsic tightness. Providers should obtain x-rays of all the joints of the involved fingers as well as the hand and wrist of the patient. The classic and still most commonly used swan-neck classification scheme is that of Nalebuff where type I is a flexible PIP hyperextension deformity; type II is secondary to intrinsic tightness; type III is a fixed PIP joint extension contracture that is “intrinsic” to the joint itself, that is, the contracture does not change regardless of the degree of flexion or extension of the MCP or any other joints; and type IV is a swan-neck deformity associated with significant PIP joint degenerative changes.

Of course, patients with rheumatologic conditions require special preoperative considerations, such as medication and cervical spine management, which are typically coordinated between the surgeon, rheumatologist, and anesthesia providers. At our institution, we have a protocol based on input from anesthesia, orthopedic spine surgery, and our hand center for cervical spine management: all patients with inflammatory arthropathies that may affect cervical spine stability obtain cervical spine x-rays consisting of A/P, lateral, and flexion and extension lateral x-rays a maximum of 1 year before a pending elective extremity surgery. We typically indicate on the x-ray prescription to include measurements of c1 to c2 translation, subaxial translation, or presence of basilar invagination. If any of the following are found on these screening films, then the patient is referred to a physician who treats cervical spine patients, such as PM&R or ortho-/neurospine surgery, to determine if any further investigations/treatments are needed before proceeding with elective extremity surgery: subaxial translation of greater than 3 mm, c1 to c2 translation of more than 4 mm, and any degree of basilar invagination. Depending on the patient’s overall presentation, extent of planned procedures, and other preoperative recommendations, surgeons may perform the swan-neck procedures under local or regional nerve block or via general anesthesia.

TECHNIQUE

Procedures to Correct MCP-Primary Flexible Swan-Neck Deformity

MCP-primary deformities typically present in patients with inflammatory arthropathies. In these cases, the MCP synovitis eventually leads to attenuation of the extensor hood, especially the radial sagittal band, and ulnar translocation of the extensor tendons. The proximal phalanx (P1) progressively migrates palmarly and ulnarly until the MCP joint is subluxated or even permanently dislocated in this position. As the extensor tendons become scarred in the ulnar gutter of the MCP joint and the base of P1, the MCP joint rests in a palmar-ulnar position leading to shortening of the extrinsic and intrinsic extensor mechanisms, especially on the ulnar side of the finger. This can lead to an increased PIP extension moment and an initially flexible swan-neck deformity. If the MCP disease is caught before it becomes a fixed situation, then surgical correction at this level may be enough to correct the swan-neck deformity and prevent it from worsening. However, the tendency toward swan-neck posturing classically becomes accentuated when surgical attempts are made to correct a fixed MCP deformity. In these cases, MCP arthroplasty, by correcting the joint subluxation, often effectively lengthens the digit and consequently further tensions the shortened extrinsic and intrinsic extensor mechanisms. Centralizing the previously subluxated extensor tendon also increases the extension force at the PIP joint. The combination of these changes can worsen the swan-neck deformity (Fig. 12-2). In these cases, a central extensor tenolysis and intrinsic release at the level of the lateral bands can help. If the deformity is still not corrected, one of the lateral bands may be excised, typically the ulnar side to help counter ulnar drift tendencies. If this still does not achieve correction, the surgeon may have to shorten the MCP arthroplasty by removing more distal metacarpal or more proximal P1. The goal at each stage of attempted correction is to not have a resting swan-neck deformity and for the surgeon to be able to easily passively flex the PIP joint whether the MCP joint is flexed or extended.

Procedures to Correct PIP-Primary Flexible Swan-Neck Deformity

Flexor Digitorum Superficialis Tenodesis of the PIP Joint In inflammatory arthropathies, the PIP joint can become synovitic with subsequent attenuation of the surrounding soft tissues, especially the volar plate or the dorsal extensor mechanism. If the volar plate is more significantly attenuated, then PIP hyperextension and swan-neck deformity ensue. If the dorsal extensor mechanism is more significantly affected, then a boutonniere deformity is the result and is covered elsewhere in this book. As the PIP joint hyperextends and the transverse retinacular ligament becomes attenuated, the lateral bands become centralized dorsally and lax, which results in less extensor force at the DIP joint. This, combined with unopposed and even increased flexion force from the increased tension on the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), leads to the DIP flexion deformity. Flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tenodesis of the PIP joint is a simple and effective technique to correct a flexible PIP hyperextension deformity (E.F. Shaw Wilgis, MD and Neal B. Zimmerman, MD, personal communication) (3). The surgeon should use his or her preferred palmar approach to the finger; I favor a midaxial incision. The C1 and A3 pulleys over the PIP joint are removed. Excursion of the FDS and FDP can be checked at this point to ensure that a flexor tenosynovectomy or tenolysis is not required. One slip of the FDS is transected just distal to Camper’s chiasm, leaving the middle phalanx (P2) insertion of the slip intact. The proximal end of the slip is then used to flex the PIP joint to a desired flexion position. We usually expect tendon transfers and tenodeses to stretch out over time, especially in patients with rheumatologic or other soft-tissue disorders. Therefore, a prudent amount of PIP flexion contracture is approximately 20 to 30 degrees to try to balance between preventing recurrence of the deformity and causing a functional limitation due to the contracture. When the desired degree of PIP flexion is achieved, the slip of FDS is sutured to the proximal phalanx (P1). Either the slip can be sutured to the edge of the flexor sheath or a suture anchor can be placed in the P1 to which the slip can be secured. A variation on this technique is similar to the Zancolli FDS volar MCP tenodesis, in this case transecting a slip of FDS, bringing it through a slit in A2, and suturing it back to itself distally in the desired PIP flexion position. However, that technique requires more dissection, may be more likely to stretch out over time, and may cause more adhesions in zone 2. Having said that, I have performed both procedures and both are certainly acceptable without any clear difference in outcomes in the reported literature; I agree with Dr. Wilgis and Dr. Zimmerman that the first technique is simpler and effective. In fact, this procedure can also be performed in the palm with the FDS tenodesis occurring at the A1 pulley level (4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree