Paul A. Lotke

Stiffness after Total Knee Replacement

INTRODUCTION

Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) can be a debilitating problem, significantly affecting the outcome and disappointing both the patient and the surgeon. Fortunately, it is relatively uncommon. Although recognized as a problem for many years, it has received relatively little attention in literature. This chapter reviews stiffness after TKA, defining the terminology, discussing the etiology, reviewing the recommendations for treatment, and identifying some of the unique surgical problems associated with limited motion.

INCIDENCE

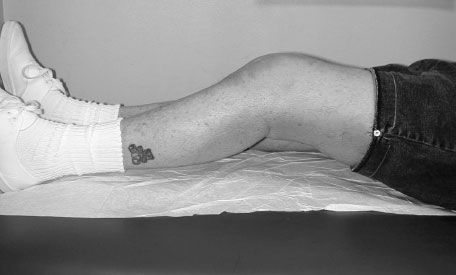

Establishing the incidence of stiffness after TKA requires not only a uniform notion of what constitutes a stiff knee but also accurate reporting. Both are elusive; the term “stiffness” after total knee has not been well defined in the literature. For the purposes of this section, we define stiffness as <75 degrees of flexion or more than a 15-degree flexion contracture in patients after TKA1,2 (Figs. 54-1 and 54-2). Using these criteria, only 1.3% of the patients will have a stiff total knee.2 However, with less stringent criteria, others have reported that 6.3% of patients have limited motion.3 Lam noted that 2.4% had flexion contractures >10 degrees, 2.1% had flexion <90 degrees, and 1.8% had both.

FIGURE 54-1. Stiff total knee with <75 degrees of flexion.

FIGURE 54-2. Stiff total knee with more than a 15-degree loss of full extension.

In analyzing causes of revision knee arthroplasty, Sharkey4 noted that arthrofibrosis was the fifth most common reason for reoperation, behind wear, loosening, instability, and infection.4 Loss of motion is usually recognized early in the postoperative course. If there are no significant external events like infection or hematoma, most patients developing limited motion are identified within 6 weeks of surgery. Although early interventions, such as manipulation (Maloney), appear to reduce the final incidence of stiffness, there is a group of patients who never develop full motion, and that is the subject of this chapter.

ETIOLOGY

Several factors have been associated with reduced motion after TKA. Some are truly causative of this outcome, and others are merely predictive. The one factor that clearly predicts the final range of motion in many studies is preoperative range of motion.5 Ritter et al.6 were the first to statistically show that the strongest predictor of postoperative flexion, regardless of alignment, was preoperative flexion. Later, they7 utilized a large database of 3,066 patients with 4,727 knees and their regression analysis. They noted that preoperative flexion is the single most important predictor of postoperative motion after TKA. Other factors, which correlated with limited motion, included intraoperative flexion, female gender, preoperative tibiofemoral malalignment, and the need for posterior capsular release. Removal of the posterior osteophytes also was associated with limited loss of motion.

Many authors have demonstrated or speculated on a variety of factors that may be associated with stiffness.1–3,8 These have included technical errors like tightness of a retained posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), elevation of the joint line, increased patellar thickness, tightness of the flexion gap, excessive patellar tilt, unresurfaced patella, overzealous physical therapy, oversized components (Fig. 54-3) or overstuffing of the polyethylene inserts, anterior tibial slope, and laxity in flexion. Finally, occult infection may be an underdiagnosed source of stiffness, and an appropriate evaluation should be initiated.

FIGURE 54-3. Stiffness in total knee possibly due to oversized femoral component.

There have also been a variety of biological conditions, which may affect motion. These include ankylosing spondylitis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis,9 infection, complex regional pain syndromes, heterotopic ossification (Fig. 54-4), and a biologic predisposition to scar (arthrofibrosis). Patients with ankylosing spondylitis are particularly prone to loss of motion after TKA, and 20% may have heterotropic ossification.10

FIGURE 54-4. Stiffness in total knee arthroplasty with heterotopic ossification.

Heterotropic ossification is not commonly noted after TKA,11,12 but it can cause stiffness, and it may be an indicator of occult infection.13 Barrack noted that the incidence of heterotropic ossification in poorly functioning total knees prior to revision surgery was 23% and increased to 56% after surgery. Heterotropic ossification was also noted to be present in 76% patients with an infection. It was not associated with gender, body mass, operative time, surgical approaches, or prior surgeries. Experience with the use of radiation therapy in prevention of heterotopic ossification following TKA is limited. Chidel et al.14 reported a series of six TKAs with symptomatic heterotopic ossification treated with surgical resection of the ossification and postoperative radiation therapy. The use of prophylactic radiation therapy did limit heterotopic ossification recurrence.

One interesting study by Keays et al.15 correlated the use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) to reduced range of motion in the early postoperative period. Comparing patients on aspirin chemoprophylaxis to a group on LMWH, they noted a significant reduction in motion during the early postoperative period in the LMWH group. But after 1 year, the results equilibrated. It can be speculated that increased perioperative bleeding may have contributed to this observation.

The benefits of physical therapy on range of motion have been debated. It is clear that overzealous therapy may irritate the knee joint in the postoperative period after arthroplasty and cause temporary swelling and limitation of motion. It is unclear if this causes long-term loss of motion. A vicious cycle may further compromise the recovery of motion as patients with reduced range of motion after total knee surgery are subject to increasingly vigorous physical therapy in order to prevent this loss. Increasing therapy for those patients destined to become stiff appears to offer little benefit, and paradoxically may hasten the inflammation and stiffness.

There is also some debate as to whether or not physical therapy after the first few days affects the range of motion. Rajan et al.16 noted in a prospective randomized study that receiving physical therapy offered no advantage in range of motion compared to a group who did not receive any outpatient therapy after total knee surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree