Sternoclavicular Joint Injuries

CASE PRESENTATION

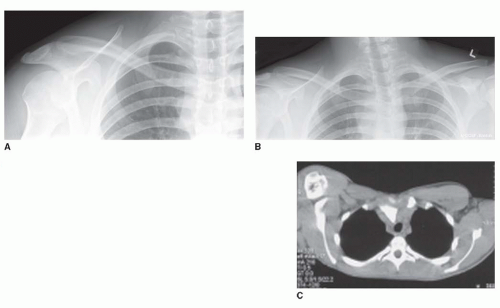

A 16-year-old right hand-dominant male presents for evaluation of right shoulder and chest discomfort after being checked into the boards during an ice hockey game. He has tenderness and swelling over the medial clavicle, and he reports some mild discomfort while swallowing. His parents report that his voice “sounds hoarse.” Neurovascular examination of the right upper limb and hand is normal. A clavicle x-ray is taken and interpreted as being normal. Subsequent imaging identifies a posteriorly displaced sternoclavicular dislocation (Figure 24-1). A pediatric hand and upper extremity surgery consultation is requested.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

How do sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) injuries present?

What are the anatomic stabilizers of the SCJ?

How is the SCJ best evaluated radiographically?

How are SCJ injuries classified?

What are the indications for surgical treatment of SCJ injuries?

How is surgical reduction and stabilization of acute SCJ injuries performed?

What are the surgical techniques for chronic SCJ instability?

What are the expected outcomes and potential complications of surgical treatment?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

The real superstar is a man or a woman raising six kids on $150 per week.

—Spencer Haywood

Fractures and dislocations of the SCJ are unusual but potentially devastating injuries in children and adolescents. Historically, most injuries have been observed or treated nonoperatively. Prior treatment principles were undoubtedly based upon fear of iatrogenic injury to adjacent anatomic structures and false assumptions regarding remodeling and longer term outcomes. Better understanding of the pathoanatomy, natural history, potential outcomes, and surgical reconstructive strategies of SCJ injuries has improved our ability to restore more normal shoulder girdle anatomy and mechanics in efforts to improve functional outcomes. We advocate surgical reduction and stabilization of acute traumatic posteriorly displaced SCJ injuries, as well as ligament reconstruction in cases of chronic post-traumatic instability associated with pain and functional limitations refractory to activity modification and therapy.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Fracture dislocations to the SCJ are uncommon injuries, representing <5% of shoulder girdle injuries.1,2 Usually arising from high-energy mechanisms of injury (e.g., falls from a height, motor vehicle collisions, sports-related injuries), both direct and indirect trauma to the ipsilateral shoulder may result in SCJ injuries. Obtaining a history of prior trauma is critical, as atraumatic cases of SCJ instability do occur—particularly in children and adolescents—and the natural history and results of treatment are quite different than in traumatic cases.3,4 In the majority of cases, displacement of the medial clavicle is anterior, typically resulting from a direct lateral blow to the shoulder with the shoulder extended. Posterior displacement is less common, usually resulting from indirect forces imparted on the shoulder girdle with the shoulder adducted and flexed or from a direct posterior blow to the medial clavicle.

Clinical Evaluation

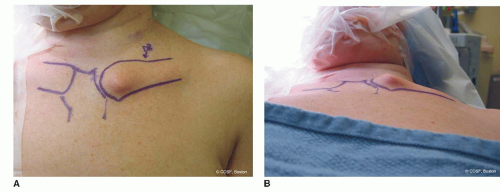

Clinical complaints and physical examination findings depend upon the pattern of injury. With traumatic anterior displacement, patients will often present with pain localized to the SCJ, tenderness, ecchymosis, and an obvious bony prominence of the clavicular head (Figure 24-2). Ranging the shoulder causes pain and/or sensation of instability. Typically, there is no associated neurovascular compromise. However, most anterior SCJ dislocations or recurrent instability are atraumatic. The atraumatic anterior dislocators will not have swelling or ecchymosis but obvious instability on exam.

FIGURE 24-2 Anteriorly displaced SCJ injury. A: Frontal and B: tangential clinical views of a left anteriorly displaced medial clavicle. |

Conversely, physical examination findings in patients with posterior SCJ injuries may be subtle. While swelling and tenderness may be seen, often there is no obvious deformity. Posterior displacement increases the risk of mediastinal compression, and some patients may have dyspnea, dysphagia, odynophagia, or hoarseness.5 In rare situations, signs of venous congestion, arterial insufficiency, or brachial plexopathy may be seen. A high index

of suspicion is critical for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention.

of suspicion is critical for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention.

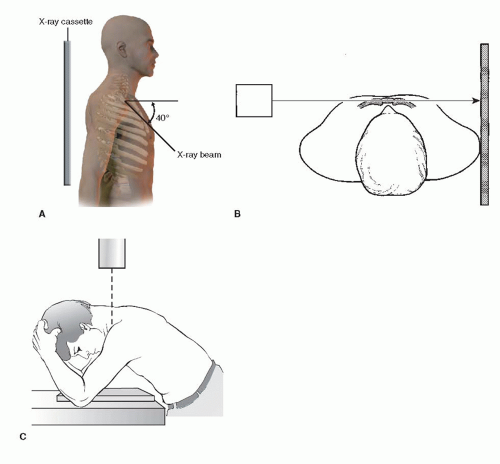

Radiographic evaluation of the SCJ can be challenging, owing to the anatomy of the SCJ and overlying/adjacent skeletal structures. An AP chest radiograph may demonstrate asymmetry of clavicular length and abnormalities in the SCJ articulation, though these findings may be subtle. Dedicated radiographs of the clavicle are centered on the clavicular diaphysis and often lack the detail needed to make the diagnosis. For this reason, a number of dedicated views have been proposed to image the SCJ (Figure 24-3). Heinig has previously proposed a tangential radiograph of the SCJ, taken with the patient supine and the cassette placed behind the opposite shoulder.6 The beam is angled in the coronal plane, parallel to the longitudinal axis of the opposite clavicle, providing a profile of the affected SCJ. Hobbs has proposed a 90-degree cephalocaudal lateral, taken with the patient seated and flexed over a table.7 The cassette is placed on the table, against the chest wall, and the beam is directed through the cervical spine. Finally, Rockwood has reported on the use of the “serendipity view,” so called due to the fact that its utility was discovered quite by accident.2 With the cassette placed behind the chest, the radiographic beam is angled 40 degrees cephalic centered on the sternum, allowing for visualization of both SCJs. In cases of anterior dislocation, the affected clavicular head will appear superiorly displaced compared to the unaffected side. Conversely, with posterior displacement, the medial clavicle will appear inferior.

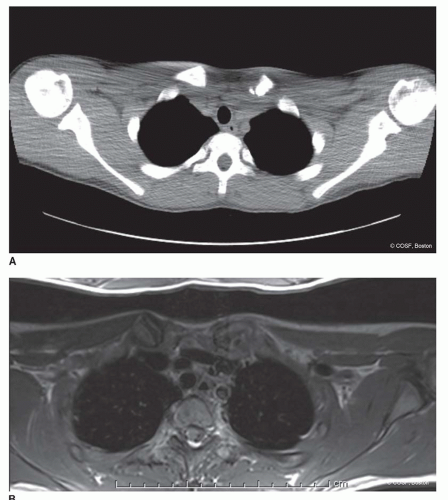

Given the difficulties with plain radiography in imaging the SCJ, three-dimensional imaging with the use of CT scans has increasingly become the standard of care for radiographic diagnosis (Figure 24-1C). With improved resolution and imaging techniques, the distinction between physeal fractures and true joint dislocations may be made (Figure 24-4). Furthermore, simultaneous assessment of compression or injury to the adjacent soft tissue structures (e.g., esophagus, trachea, brachiocephalic vessels) may be made.

Surgical Indications

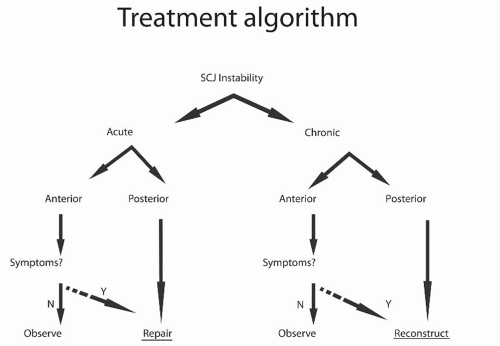

In general, a number of principles guide the treatment of SCJ fracture dislocations (Figure 24-5). First, the acuity or chronicity of an injury must be considered, as nonoperative or surgical treatment options are influenced by the time from initial injury. Second, the direction of displacement must be taken into consideration. While anterior injuries may cause little pain or functional compromise, posteriorly displaced injuries may result in compression of the adjacent mediastinal structures. Third, the severity of symptoms, if any, must be noted to weigh the risks and benefits of intervention. Finally, patient demands play an important role in the decision-making process, particularly in laborers or overhead athletes.

Unfortunately, there is a paucity of information regarding the natural history of untreated SCJ injuries. For this reason, treatment recommendations and results of surgical intervention have not been carefully compared with the natural history of the condition. As a result, symptomatic relief and avoidance of acute or late complications remain the factors driving treatment recommendations. In particular, unrecognized or untreated traumatic posterior SCJ injuries may lead to a host of potentially devastating complications. Tracheal stenosis, esophageal compression, pneumothorax, great vessel compromise, brachial plexopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome, sepsis, and even death have been reported in these instances. Furthermore, many

of these complications can be seen in initially asymptomatic patients.5

of these complications can be seen in initially asymptomatic patients.5

Based upon these considerations, we believe indications for surgical treatment of SCJ injuries include (1) acute, traumatic posteriorly displaced injuries and (2) chronic, recurrent instability with pain and functional limitations despite activity modification and physical therapy. Surgical treatment is resisted in patients with atraumatic or voluntary anterior SCJ instability until there clearly is no other alternative (see Coach’s Corner).

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

In general, surgical procedures for SCJ injury fall into one of three categories: repair, reconstruction, or resection. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and the choice of surgical technique is driven by the chronicity of instability, the direction of displacement, and the status of the articular surfaces of the clavicle and sternum.

• Observation of Acute Anterior Dislocation

The optimal treatment of acute anterior SCJ fracture dislocations is controversial. Symptomatic management alone with sling immobilization followed by gradual return to activities has been advocated with the expectation of return of shoulder motion and strength.8 Patients should be counseled about the likelihood of a persistent bony prominence in the region of the clavicular head. In young patients with physeal fractures, remodeling of bony deformity may be seen with continued skeletal growth. Others have recommended closed reduction under conscious sedation or general anesthesia. Reduction maneuvers involve scapular retraction and posteriorly directed pressure over the medial clavicle, followed by application of a figure-of-eight strap. While reduction may often be achieved, recurrent instability is commonplace. Surgical techniques of open reduction and ligament repair or reconstruction are not routinely utilized in acute, traumatic cases. Again, closed reduction maneuvers or surgical reconstructions should be generally avoided in patients with atraumatic or voluntary anterior SCJ instability. Our preference is to treat anteriorly displaced injuries symptomatically with sling immobilization and observation.

▪ ORIF of Acute Posterior Dislocation

Treatment considerations are different for acute posterior SCJ fracture dislocations, in part due to the potentially disastrous sequelae of unreduced posterior injuries. Closed reduction has been proposed by many as definitive, particularly given the remodeling potential of the medial clavicle and thus its ability to accept a nonanatomic reduction.2,9 Closed reduction is typically performed under general anesthesia via manipulation of the shoulders with abduction-traction, adduction-traction, or scapular

retraction. Percutaneous techniques of controlling the medial clavicle (e.g., towel clip or screw) during reduction maneuvers have been advocated. More recent information, however, suggests that while an initial reduction may be achieved, recurrent instability is very common.5,10,

retraction. Percutaneous techniques of controlling the medial clavicle (e.g., towel clip or screw) during reduction maneuvers have been advocated. More recent information, however, suggests that while an initial reduction may be achieved, recurrent instability is very common.5,10,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree