Sports-Related Conditions and Injuries

Lisa L. Willett

|

A 52 year old male with type 2 diabetes mellitus began an exercise program to improve his diabetic control. He has been playing tennis three times a week for the past month. He presents to his physician complaining of right shoulder pain. The pain is worse in certain positions.

Sporting activities are an important component of a healthy lifestyle. Patients of all ages are encouraged by physicians to exercise for health benefits. However, sports activities can lead to injuries. As our adult population ages and a larger proportion of the population embraces healthier lifestyle, sports-related conditions and injuries are predicted to increase.

There are many types of sports-related injuries, ranging from chronic overuse to traumatic injuries. Lower extremity overuse injuries occur from jogging, walking, jumping, or cycling. Examples of chronic overuse injuries include patellofemoral pain syndrome and Achilles tendinitis. Of the overuse injuries of the upper extremity, both rotator cuff tendinitis and lateral epicondylitis are the most common. Injuries related to trauma can result from high-impact sporting activities, and include ligament tears (such as an anterior cruciate ligament tear), ligament sprains (lateral ankle sprain), fractures, joint dislocations, or head injuries. The epidemiology of sporting injuries is limited. In studies (1), lower extremity injuries are more common than upper extremity, with the most common sites being the knee and ankle.

Injuries of the Rotator Cuff

Clinical Presentation

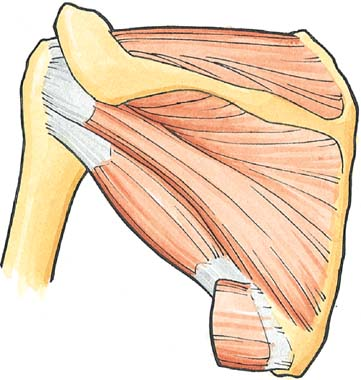

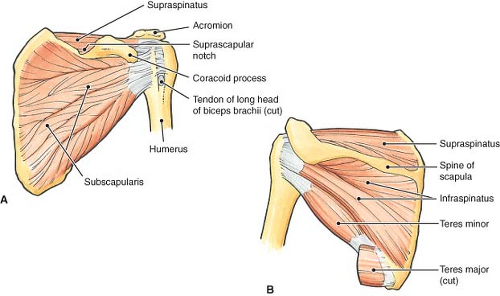

Rotator cuff tendinitis is common in athletes who participate in repetitive overhead activities, such as softball, baseball, tennis, or golf. The rotator cuff is comprised of four muscles, the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, whose tendons attach to the proximal humerus (Fig. 8.1). Impingement of the tendons between the head of the humerus and the acromion can lead to inflammation and subsequent tears of one or more of the tendons. The supraspinatus is the most frequently involved. Symptoms include “ache-like” shoulder pain, often worse at night, exacerbated by abduction or flexion of the arm as well as activities that involve overhead movement of the arm. If the tear is complete, patients may note weakness and decreased range of motion (2).

Examination

The physical exam findings vary depending on which of the four tendons are involved, and the degree of injury. If there is only inflammation, the patient will experience pain; partial or full-thickness tears results in weakness and decreased range of motion. Although over 20 maneuvers have been described to test rotator cuff tears, the 3 maneuvers most useful for predicting a rotator cuff

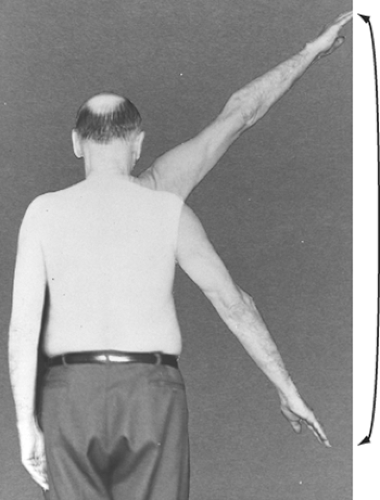

tear are: supraspinatus weakness, weakness in external rotation, and a positive impingement sign (3,4). The test to elicit supraspinatus weakness (“empty can sign”) involves having the patient abduct his arm to 90 degrees, with 30 degrees forward adduction. With the patient’s thumb pointing down toward the floor, the examiner pushes down on the arm at the distal humerus as the patient resists. To elicit weakness in external rotation, a finding consistent with infraspinatus compromise, the patient holds his arms against his torso, flexes his elbows at 90 degrees with the thumbs turned up and the arm rotated internally 20 degrees. The patient is then asked to externally rotate the arm against the examiner’s resistance. A positive impingement sign (Fig. 8.2) is elicited with the arm down, externally rotated and then passively elevated to an overhead position. The patient will experience pain with internal rotation of the arm. Another maneuver, the painful arc sign (Fig. 8.3) can be helpful to exclude a rotator cuff tear; a positive is interpreted when pain is elicited with active range of motion between 60 and 100 degrees of abduction and it has a high sensitivity (97.5%) for rotator cuff tear. Therefore, if this sign is absent, the patient is unlikely to have a tear.

tear are: supraspinatus weakness, weakness in external rotation, and a positive impingement sign (3,4). The test to elicit supraspinatus weakness (“empty can sign”) involves having the patient abduct his arm to 90 degrees, with 30 degrees forward adduction. With the patient’s thumb pointing down toward the floor, the examiner pushes down on the arm at the distal humerus as the patient resists. To elicit weakness in external rotation, a finding consistent with infraspinatus compromise, the patient holds his arms against his torso, flexes his elbows at 90 degrees with the thumbs turned up and the arm rotated internally 20 degrees. The patient is then asked to externally rotate the arm against the examiner’s resistance. A positive impingement sign (Fig. 8.2) is elicited with the arm down, externally rotated and then passively elevated to an overhead position. The patient will experience pain with internal rotation of the arm. Another maneuver, the painful arc sign (Fig. 8.3) can be helpful to exclude a rotator cuff tear; a positive is interpreted when pain is elicited with active range of motion between 60 and 100 degrees of abduction and it has a high sensitivity (97.5%) for rotator cuff tear. Therefore, if this sign is absent, the patient is unlikely to have a tear.

Figure 8.1 Rotator cuff muscles. A, anterior; B, posterior. The supraspinatus (A and B), infraspinatus (B), teres minor (B), and subscapularis (A) canvas the perimeter of the glenohumeral joint capsule. (From Moore KL, Agur AMR. Essential Clinical Anatomy, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002. Figure 7.12, p. 425.) |

Studies

If the exam and history are consistent with rotator cuff tendinitis, further studies are not necessary. However, if the pain persists, plain radiographs are indicated. Superior migration of the humeral head can be seen if a large rotator cuff tear is present. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred test for diagnosing rotator cuff disorders, although ultrasonography is emerging as a cost-effective alternative with similar sensitivity and specificity.

Treatment

Multiple therapies are available to treat rotator cuff injuries. Nonoperative therapy consists of 6 weeks to 3 months of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS), intra-articular steroid injections, passive and active exercises with physical therapy, plus heat, cold, or ultrasonography therapy. Patients who fail nonoperative treatment can be referred to orthopedics for surgical repair with open, mini-open, or arthroscopic techniques. In a systematic review of 137 studies of nonoperative and operative treatments (5), evidence was not conclusive to recommend one therapy over another. Older age, increased size of the tear, and greater preoperative symptoms were associated with recurrent tears. Duration of symptoms was not associated with poorer outcomes.

Clinical Course

Regardless of the treatment approach, the majority of patients with rotator cuff injuries improve.

Clinical Points

Overuse injuries are common when patients begin exercise programs.

Lower extremity injuries are more common than upper extremity, with the most common sites being the knee and ankle.

The most common cause of knee pain amongst patients exercising is patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Conservative management with rest, ice, physical therapy, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents is effective first line therapy.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is one of the most common sports injuries, and the most common cause of knee pain (1). It is seen in sports involving running, jumping, quick stops, and turning. The cause of patellofemoral pain is due to malalignment of the patella as it tracks in the trochlear groove of the femur. Symptoms of PFPS include unilateral or bilateral anterior knee pain, described as a dull ache in the peri- or retro-patellar region of the knee. It is initiated by the sporting activity, but can progress to become constant. Pain is exacerbated by squatting, walking up or down stairs, and prolonged sitting. It is also known as chondromalacia patellae or patellofemoral joint syndrome (2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree